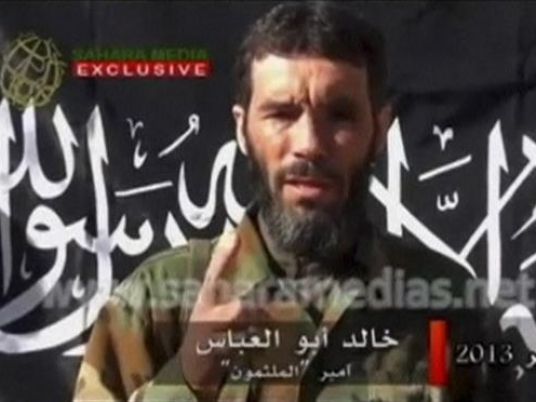

He lost an eye in Afghanistan, was earlier reported dead in fighting in Mali and now Libya says he was killed in a US air strike at the weekend. But is the Algerian jihadist dubbed "The Uncatchable" for his decades-long elusiveness really dead?

US officials have yet to confirm Libyan reports that Mokhtar Belmokhtar was killed in eastern Libya, saying on Monday only that the F-15 jet raid appeared to have succeeded but stopping short of confirming his demise.

Doubts were well placed: Belmokhtar, who was in his early 40s, has been reported dead several times only to reappear in jihadist propaganda claiming responsibility for new attacks.

What is undisputed is that the raid attested to a Libya sliding deeper into armed anarchy since the 2011 fall of Muammar Gaddafi that Western nations fear is creating a jihadist safe haven just across the Mediterranean from Europe.

With two rival Libyan governments and their armed factions battling for control, Islamic State and other jihadist groups like Belmokhtar's have exploited the chaos to seek refuge, train and expand their influence in the vast North African country.

Libyan military officials said on Monday that up to 17 Al-Qaeda insurgents had been killed in the air strike while they were meeting near Benghazi, but did not name any. A US official, speaking to Reuters on condition of anonymity, said around two dozen militants may have been killed.

"The strike carried out by US forces was on a farm in the industrial district while Belmokhtar was holding a meeting with other militant leaders," a Libya military source told LANA state news agency.

The Pentagon was more cautious on Belmokhtar's fate. "Initial assessments are that it was successful. But we have not finalized our determination," said spokesman Colonel Steve Warren, adding that the United States consulted with the internationally recognized Libyan government before the strike.

French President Francois Hollande, on a visit to Algiers, said he could not confirm the result of the operation, but said information led officials to believe Belmokhtar was dead.

"There is a very big possibility that Belmokhtar was killed," Hollande told reporters.

Even before Libya began unraveling as a state, its long barely governed southern desert served as a base for Belmokhtar fighters when he masterminded a 2013 attack across the border into Algeria on the In Amenas gasfield. Forty oil workers, mostly foreigners, were killed in the jihadist assault.

Unanswered questions over Belmokhtar's fate would suit a man born in Algeria's central desert who rose through jihadist ranks during its 1990s civil war and survived on the run to become one of the most renowned men in Saharan militant circles.

Once with Al-Qaeda's North African branch, he split to form his own militant group called "Those Who Sign in Blood". He was involved in kidnapping several foreigners, took part in Mali's separatist conflict and ran lucrative Saharan smuggling rings.

Well-connected

"Belmokhtar is one of the longest-standing and most connected jihadist leaders of the region, where he has been active for more than a decade," said Chris Chivvis, an associate director at the RAND International Security and Defense Policy Center and author of "The French War on Al-Qaeda in Africa".

"His personal ties to the tribes of the region, experience, and authority are very important to the cohesion and success of his current group," Chivvis said of the man called "The Untouchable" by the French intelligence services.

Belmokhtar followed a well-worn path to jihad, leaving home to fight in Afghanistan when he was 19, according to interviews on militant websites, and returned to Algeria in the throes of an Islamist militant insurgency.

That was the start of a two-decade career of militancy, first as a member of Algeria's Islamic Armed Group (GIA) in the country's 1990s civil war, then as a joint founder of the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat.

His group later entered the franchise of Al-Qaeda's North Africa wing, known as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Belmokhtar headed one of two AQIM battalions bordering Mali.

He eventually split with the fellow Algerian leader of AQIM and built his own group. But the Pentagon said Belmokhtar maintained his allegiance to Al-Qaeda.

Experts say he was always less of an Islamist ideologue than a "gangster-jihadist" involved in trafficking of arms, smuggling and contraband.

Security experts said his death, if confirmed, could crimp his group's effectiveness in the short-term because of his personal connections in the region, though his organization will have others well-placed to re-establish its clout.

"More often than not, when the head of the snake is cut off, a more venomous one grows in its place," said Geoff Porter, a North African expert at West Point's Combating Terrorism Center. "That is certainly a possibility here –- and there are no shortage of aspiring jihadis who are likely eager to pick up Belmokhtar's mantle."

But the loss of such a central figure may also trigger more competition between criminal gangs, especially over wealth derived from smuggling in arms and migrants, leading to infighting and possible driving some into rival groups like the ultra-hardline Islamic State, also known as ISIS.

"If Belmokhtar is indeed gone, this group, which operates from Mali through Libya, will be less effective and less of a threat," RAND's Chivvis said. "This does not mean it will go away, however. To the contrary, parts of it might decide they now want to throw their lot in with ISIS."