Mohamed Reda, a professional driver by day and musician by night, can distinctly remember the first time he came across the “Change Your Book” initiative on the streets of Greater Cairo’s Shubra al-Kheima neighborhood.

“It was my son’s 10th birthday, and I had yet to buy him something because I did not have money at the time,” he says.

Riding on his motorbike, they were on the way to a cousin’s house when they found themselves in front of several tables of books.

“We got off the motorbike, and my son Youssef was enthralled by all the books on the table, so we stopped and looked through some,” Reda continues. “I typically always have a book with me, so when Youssef came across an Arabic comic book, I was able to easily swap my book for the comic. It remains one of the best presents because Youssef continues to read comics now. In fact, he claims that he wants to write comic books when he is older.”

It was in 2009 that Ahmed Hassan first came up with the idea to organize a book swap.

“You always hear that people in Egypt do not read,” he says. “But that is an incomplete sentence. Sure, people in Egypt do not read, but it is because of many reasons. Mostly it is the poverty — books are expensive — but it also has to do with the fact that there are no real libraries in Egypt, which makes books inaccessible to your average Egyptian.”

Main libraries in Egypt include the Misr Public Library in Giza, the National Library and Archives, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina and the Greater Cairo Library in Zamalek, which has been closed for nearly two years while undergoing renovations. Ahmed Ali Morsy, former Egyptian National Library chairperson , says that under former President Hosni Mubarak there was an initiative to open public libraries in various Egyptian governorates, but because of limited funding and resources, most of the libraries have likely fallen by the wayside due to their poor conditions.

Meanwhile, while refusing to accept that “people in Egypt do not read,” Hassan and friends continued working on their plans to address the staggering illiteracy rates and lack of accessibility to books.

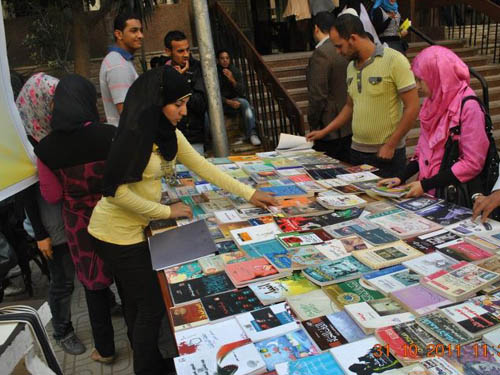

It did not take long for them to come up with the idea for a street-side book swap. The concept is simple: Visitors or passersby donate a book and, in return, they take a book of their choosing.

There is no monetary exchange or questions asked, and any book can be donated or swapped.

“We currently have about 7,000 books,” explains Hassan. “As of now, we have successfully swapped close to 5,000 of those books. If you consider that each book costs about LE10, then that is a lot of money we have saved people.”

In only a few short years, the book swap has visited various governorates within Egypt. “Change Your Book” is typically organized about five times a year. It has taken place within cities and neighborhoods such as Tanta, Shubra and Port Said.

Hassan says the book swap has also visited Cairo University, Ain Shams University and the Faculty of Fine Arts in Alexandria, in addition to factories such as the Eastern Tobacco Company in Haram and various cultural institutes.

“We soon realized that the book swap works best when someone from an institute calls us to organize it. That way we do not have to deal with the cops on the street hassling us for licenses and all the costs that go into renting tables and delivering the books,” says Hassan.

But “Change Your Book” is not the only cultural development initiative Hassan has been working on. He also spearheads the art and development organization Eltak3eiba Center, which is headquartered in Shubra al-Kheima.

He explains that the idea for Eltak3eiba Center came about after the disastrous and tragic fire that engulfed the Beni Suef Cultural Palace in 2005 — the fire claimed the lives of 46 people and caused even more injuries.

“When Beni Suef burned down, we lost a lot of friends. It was awful,” says Hassan, who explains he was active in the theater scene there and, like many others, Beni Suef was an important cultural hub for him. Hassan adds that it was around that time, in 2005, that the Rawabet Theater was built, and as a result, downtown Cairo was reclaimed as a cultural hub for independent arts and development.

“Because of this, we drifted more to the centralized art scene in downtown Cairo, where it was always the same circle of people. The thing about Beni Suef was it had a broader reach of artists and audiences,” he adds.

Hassan does acknowledge that Rawabet Theater has done an excellent job over the years.

“But what I noticed was that most people from my neighborhood did not have the luxury of being able to go downtown simply to be active in the arts. So that is what Eltak3eiba aims to do. We want to make art accessible to those who live in the Shubra neighborhood,” he says.

With that mindset, Eltak3eiba Center was founded in 2007, and the book swap was a natural development down that path. It continues to operate under the Eltak3eiba umbrella; both initiatives attempt to make art, knowledge and culture accessible by working directly within the Shubra community, instead of the centralized downtown scene.

“There are artists and writers everywhere you look in Egypt,” exclaims Hassan. “You can always find someone on the street drawing something, or sitting and writing. That is the whole point of all this, to bring resources to the people, instead of expecting the people to come to you. That is how you cultivate new artists.”

For several years, Eltak3eiba Center organized various cultural events, workshops and festivals without having any official paperwork or funds. Hassan says those involved have been working “out of the goodness of their heart.”

He says it is a collective of cultural activists who simply want to do community outreach. Only recently has it become a registered NGO, with its official space set to open in Shubra al-Kheima by the end of the month.

The center plans to operate both in Shubra and downtown in order to bridge the gap between artist and audience.

And while there are many art-based NGOs to develop over the past few years, what is different about Eltak3eiba Center is its emphasis on addressing the main issues within the Shubra community.

“You have to understand something about Shubra,” explains Hassan. “It is an extremely poor neighborhood that is very densely populated. And what is worse is that there are thousands of street children.

“They do not get to go to the mall, or gardens to play. Their only space is the street. And when you are always in the street, you forget about the beauty in this world — all you see is trash and cars,” he says.

Art is the one thing that allows a person to really think freely, he says.

“It allows you to be creative and it forces you to ask ‘why?’ And when you learn to ask ‘why’ in art, it opens up critical thought on all levels — even politically. Art gives you your individuality, and that is so needed these days,” says Hassan.

To find out more information about Eltak3iba Center’s workshops and programs or to request for “Change Your Book” to visit your neighborhood, visit their Facebook page.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.