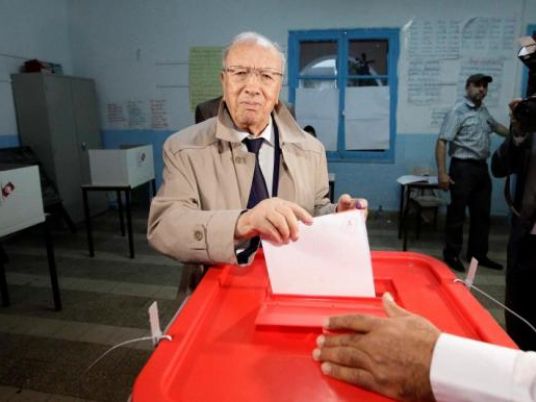

Tunisian presidential candidate Beji Caid Essebsi claimed victory in Sunday’s run-off election, which is seen as the final step to full democracy nearly four years after an uprising ousted Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali.

Preliminary results were still to be released by election authorities, but soon after polls closed, Essebsi said he had beaten rival Moncef Marzouki, the incumbent president.

“I dedicate my victory to the martyrs of Tunisia. I thank Marzouki, and now we should work together without excluding anyone,” Essebsi, a former parliament speaker under Ben Ali, told local television.

His campaign manager said “initial indications” showed the 88-year-old Essebsi had won without giving any details, as hundreds of celebrating supporters chanted “Beji President” and waved Tunisia’s red and white national flag.

However, rival campaign manager for Marzouki, Adnen Monsar, dismissed the claims saying it was a very close call. “Nothing is confirmed so far,” he told reporters.

With a new progressive constitution and a full parliament elected in October, Tunisia is hailed as an example of democratic change for a region still struggling with the aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring revolts.

Tunisia avoided the bitter post-revolt divisions troubling Libya and Egypt, but tensions sporadically flare.

One gunman was killed overnight and three arrested after they opened fire on a polling station in the central Kairouan governorate, a defence ministry official said.

Essebsi took 39 per cent of votes in the first round ballot in November with Marzouki winning 33 percent.

As front runner, Essebsi dismissed critics who said victory for him would mark a return of the old regime stalwarts.

He argued that he was the technocrat Tunisia needed following three messy years of an Islamist-led coalition government.

Marzouki, 69, is a former activist who once sought refuge in France during the Ben Ali era. He painted an Essebsi presidency as a setback for the “Jasmine Revolution” that forced the former leader to flee into exile.

“We need a president who looks after the people and is not interested only in power,” said Ibrahim Ktiti, an electrician who voted in the poor Ettadhamen neighbourhood of Tunis.

“The old regime won’t make it back. Essebsi never excused himself for all the time he was with Ben Ali.”

Yet many Tunisians tie Marzouki’s own presidency to the Islamist party’s government and the mistakes opponents said it made in controlling the influence of hardliners in one of the Arab world’s most secular countries.

Compromise has been important in Tunisian politics and Essebsi’s Nida Tunis party reached a deal with the Ennahda party to overcome a crisis triggered by the murder of two secular leaders last year.

Ennahda stepped down at the start of this year to make way for a technocrat transitional cabinet until elections. But the hardliners remain a powerful force after winning the second largest number of seats in the new parliament.

Essebsi appeals to the more secular, liberal sections of Tunisian society, while analysts predicted that Marzouki would draw on support from more conservative rural areas, and from some members of Ennahda, which did not field a candidate.