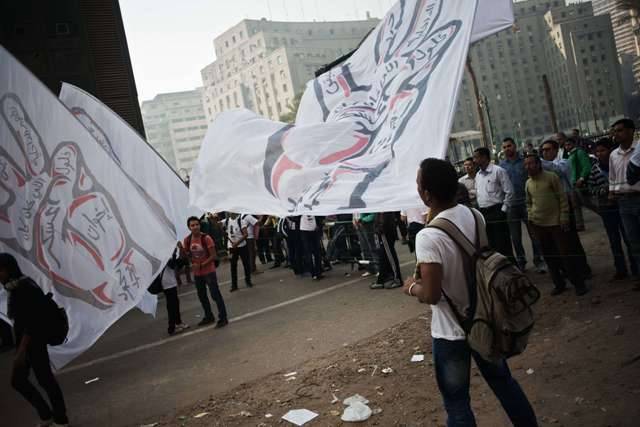

Ten days have passed since the commemoration of last year’s Mohamed Mahmoud clashes, but the area surrounding Tahrir Square remains the scene of a battlefield. Images of wounded children being rushed to field hospitals, thick white clouds of tear gas and choking, rock-throwing protesters are all too familiar.

The questions that arise are familiar as well. Who are the people on the frontline — the receiving end of the Interior Ministry’s batons, tear gas and shotgun pellets? Why do they do this? And perhaps more importantly, what do they achieve?

Akram Ismail, a member of the Socialist Popular Alliance Party, says the November 2011 clashes on the same street played an essential role in delegitimizing the then-ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The impunity with which over 40 protesters were killed was cause for hundreds of thousands to rally against army council rule and security forces.

It was this street-created momentum, many believe, that political forces fed on to pressure the army into surrendering power to civilian forces.

Something similar can be detected in the chaos of the latest street battles, Ismail says, which stopped for the funeral of Gaber Salah, the 17-year-old protester who was killed by Central Security Forces. He was shot with birdshot in the head, chest and arm and was taken off life support on Sunday.

“We have 3,000 or 4,000 youth who are apparently willing to sacrifice everything in this fight, which confronts society with the daunting question of why? Our collective conscience is then forced to ask a very elementary question: Are we going in the right direction? In other words, is the Interior Ministry a less repressive institution? Is poverty being remedied? Are our youth getting opportunities?” Ismail explains.

“Their anger and courage is an expression of the repression of the Interior Ministry and the political crisis we are in. Those fighting in Mohamed Mahmoud [and surroundings] thus bring back the central demands of the revolution to the agenda of society and of political forces, but they pay the highest price,” he adds.

The protesters this reporter spoke to gave different reasons for their presence in the line of fire. But what they have in common as a motivational factor is, at its core, a bitter resentment towards the system.

From some, there is resentment towards the Interior Ministry for killing or injuring their friends. Others feel abandoned by President Mohamed Morsy, his government, the judiciary and political parties — in other words, the entire system.

There’s a sense of abandonment because no institution or individual has delivered on promises of retribution for the martyrs. There’s the perceived failure by the ruling elite of relieving pressure on the poor, whose future prospects are described as bleak, which explains why many, if not most, on the frontline come from Cairo’s poor suburbs.

The constitutional declaration issued by Morsy on Thursday evening that granted him unprecedented powers was also mentioned by most protesters present on the frontline.

A 20-year-old who preferred to remain anonymous says he was there to “get the rights of martyrs,” and went on to list names of friends he lost, amongst them Jika, Gaber Saleh’s nickname.

“We tried to protest peacefully on 25 and 28 January [of 2011], but you know what they did to us those days. This way we revive the revolution,” he says.

Asked if the fighting would bring to justice those who killed his friends, or realize the revolution’s demands of “bread, freedom and social justice,” the protester answers: “It will, because it adds pressure on the regime.”

Another 16-year-old protester, who also wished to remain unidentified, displayed birdshot wounds to his leg and what looked like a wound from a club landing on his head as evidence of the cruelty of the Interior Ministry, “who use lethal weapons against youth with rocks.”

He was wearing a black headband inscribed with the words “retribution for the martyrs.”

This protester said he came to Cairo two months ago from Minya, an Upper Egypt governorate, to work and sleep in a bakery in Giza.

“I want to say something to Morsy. We elected you in Minya to help us, but now we have a hard time buying a loaf of bread and all the prices keep rising,” he says. He adds that it is unfair that children born to rich families enjoy rights he is denied.

“The only thing that has become cheaper is hash,” comments 20-year-old Mostafa Mohamed jokingly.

Mohamed, who also works in a bakery, is from Shagarat Maryam, a district in the Cairo suburb of Matariyya.

“We are here for our rights. I will stop throwing [rocks] if the government has some mercy on us. How am I supposed to get married, get an apartment and build up something?” he asks.

A 20-year-old from Bab al-Shariyya, injured from a rock that landed on his chest, says he would rather be at school, but that “circumstances do not allow me to.” He then runs off to pick up a teargas canister, still emanating thick white clouds, to throw back at security forces.

PSAP member Ismail thinks that the longer these clashes last, the more the Interior Ministry and the government will be discredited.

“This confrontation makes power a burden on the regime. The violence monopoly we entrust to the security forces for our protection comes under scrutiny because it is being abused, prompting intensified calls from societal and political forces for security reform, and forcing the government to come to the negotiating table,” he explains.

This, in turn, creates space for political forces to push for demands, not only because the government has to negotiate its way out, but also because, in the light of this chaos, opposition will have more ammunition to fire at the ruling elite for its failure to run its affairs, Ismail explains.

“Their existence challenges the status of the regime,” he says referring to the youth.

“They only exist because the revolution has been trampled upon, dashing their hopes and dreams. With their hate of power, hate of politics and of parties, they are the political wings of the revolution.”

Independent journalist Sarah El Sirgany, who was there during a big part of the clashes, says the violent character of protests is often the spark that leads to popular mobilization around a cause.

“Violence keeps the cause alive and prompts a bigger reaction. Instead of just shouting and leaving, some people feel like there is a real battle going on,” she says.

“The July 2011 sit-in was really big, but little direct gain came from it, probably because it was peaceful. Only when protesters were brutally killed during the November 2011 Mohamed Mahmoud [clashes] did a huge popular response materialize,” she adds.

Protesters are not necessarily driven by a logical calculation of political gains and losses.

“For two days, the fighting happened in Mohamed Mahmoud, where the security forces were using buildings as shields. It is not logical to go and fight them, because they know they cannot win that physical battle,” Sirgany says.

“But frustration runs deep, and many walk around with a vendetta because of the lack of justice and retribution. I spoke to some who have been tortured and raped in prison, others had to see their friends in morgues.”