For the past year, countries around the world have shared data on Covid-19 cases and deaths with the World Health Organization (WHO) — information that is crucial in informing the global fight against the disease.

However, three countries stand out as appearing either less than transparent or in denial about the scale of the problem.

The East African nation of Tanzania has not updated its Covid-19 data since early May, leaving the last number of reported confirmed cases at 509 and the death toll at 21.

The Central Asian nation of Turkmenistan, a secretive, highly authoritarian state, “has not reported any Covid-19 cases to WHO to date,” according to a WHO statement. But human rights groups say the disease is spreading widely there.

North Korea similarly has not recorded a single case of Covid-19. Most experts view that claim as suspect, however. The reclusive country has tested only a fraction of its nearly 26-million-strong population and has a shared border with China, where the pandemic began.

Dr. Dorit Nitzan, regional emergency director for the WHO Regional Office for Europe, told CNN 14 countries have so far reported zero cases, adding that the organization “cannot independently verify whether zero reported cases represent the true absence of cases or not.”

The WHO’s Covid-19 dashboard doesn’t differentiate between countries reporting zero cases of the virus and countries that haven’t submitted any data. However, in contrast to Turkmenistan and North Korea, the other zero-case locations are tiny, isolated island communities such as St. Helena, Kiribati and Tuvalu.

“We encourage all countries to share data — publicly or to WHO — as this allows us to track the disease globally,” Nitzan added. “As Covid-19 is a communicable disease, tracking cases is especially important, aiding in a prompt and appropriate public health response.”

In Tanzania, President John Magufuli has repeatedly downplayed the virus, urged citizens to “pray coronavirus away” and recommended outlandish cures. He has also refused to acquire Covid-19 vaccines for the population of 58 million, saying they are “dangerous” and “not good for us.”

But the deaths of two senior Tanzanian officials in recent weeks have undermined his claims, and there are signs that Tanzania may be shifting its stance.

The United States Embassy in the country’s largest city, Dar es Salaam, has warned that cases have risen significantly since January. Last week, the US ambassador to Tanzania noted that it was “critical to collect and report information about testing and cases” and urged Tanzania’s health experts to review the evidence on vaccines.

Dr. Peter Drobac, a global health expert at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School in England, told CNN that the pandemic had made it clear “how critical leadership is and how dangerous it is to have leaders who aren’t willing to admit the problem and pull people together to respond.”

For example, mixed messaging or denialism last year around basic interventions such as mask-wearing helped fuel the rapid spread of the virus in the United States and Brazil, leading to many avoidable deaths, he said.

Those countries were tracking Covid-19 data, however, and eventually pressure grew to act, Drobac said. “What’s really troubling in places like Tanzania is we don’t even have those data.”

WHO: ‘Robust action’ needed

WHO has taken the unusual step of twice calling on Tanzania in recent weeks to start providing transparent data.

Cases involving infected Tanzanians traveling abroad have underscored the need for “robust action,” WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a February 20 statement.

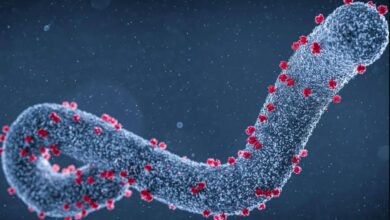

Two people who traveled from Tanzania to the United Kingdom were carrying the B.1351 variant first detected in South Africa, which seems to be more transmissible than other versions of the virus, and which might evade some of the immune protection offered by antibodies.

“WHO is yet to receive any information regarding what measures Tanzania is taking to respond to the pandemic,” Tedros said. “I renew my call for Tanzania to start reporting Covid-19 cases and share data.”

A day after the appeal from Tedros, Magufuli told churchgoers in Dar es Salaam that they should protect themselves but wear “locally produced face masks instead of importing from outside which are not safe.” The President also insisted Tanzanians should use local remedies to fight against respiratory problems, including steam inhalation, and continue to trust in prayer.

In an Instagram post the same day, Tanzanian Health Minister Dr. Dorothy Gwajima encouraged the use of traditional herbs to fight infectious diseases and denounced rumors circulating online that a second wave of coronavirus was killing many Tanzanians. Gwajima has not responded to a CNN request for interview.

But there are signs her ministry may be evolving its message. On February 25, the US ambassador to Tanzania tweeted that he was “encouraged to see the Health Ministry now urging Tanzanians to take stronger preventative measures against Covid-19, including wearing a mask, avoiding crowds, and social distancing.”

He tweeted screenshots from a Health Ministry statement dated a day earlier which says it is “very important for us to increase efforts of taking precautions,” urges Tanzanians to “wear the right masks and make sure you wear them properly, especially when attending gatherings,” and instructs people to avoid unnecessary gatherings, including in public transport locations.

Such steps are likely to be welcomed by global health experts. Denialism carries big risks, according to Drobac, the first being the human toll within the country itself.

Secondly, he said, “there’s the real risk of having out-of-control blazes in the broader wildfire of the pandemic. None of us are safe anywhere until all of us are safe everywhere.”

This makes countries neighboring Tanzania, such as Kenya and Rwanda, “really vulnerable,” and could undermine the great sacrifices they and others have made to try to contain Covid-19, he said.

Another risk is that of the uncontrolled spread of the virus leading to variants emerging that might reduce the efficacy of Covid-19 vaccines, Drobac said.

Turkmenistan

In Turkmenistan, a former Soviet republic labeled one of the world’s most repressive nations by Human Rights Watch (HRW), authorities have restricted travel and urged social distancing and mask-wearing — but they have not stated that this is because Covid-19 is circulating in the country.

Masks are needed to protect against airborne “dust,” the government said last summer.

HRW’s World Report 2021 accused the Turkmen government of having “recklessly denied and mismanaged the Covid-19 epidemic within the country,” aggravating a pre-existing food crisis, and said it had “coerced” health workers into silence over the spread of the virus.

The US Embassy in Turkmenistan says on its website that it has received reports “of local citizens with symptoms consistent with Covid-19 undergoing Covid-19 testing and being placed in quarantine in infectious diseases hospitals.” It notes that Turkmenistan “may be disinclined” officially to acknowledge any cases that are confirmed.

Diana Serebryannik, director of Europe-based exiles group Human Rights and Freedoms of Turkmen Citizens, described the situation in the country as a “disaster” because the government refused to recognize Covid-19, leaving sick people unable to access appropriate care and most doctors without the basic knowledge to treat them.

Her group, which includes two Turkmen doctors, has set up an online service offering consultations to people inside Turkmenistan who fall sick with suspected Covid-19, she said, adding that it has so far been in contact with more than 3,500 people.

“There is no recognition of that virus inside the country. And the problem is that the treatment for Covid is quite expensive and some people who are in contact with us can’t afford it,” she said, adding that costs in pharmacies for imported drugs are high. “Some people face the choice whether to buy food or to buy some kind of medicine. It’s a big problem.”

There are also insufficient supplies of oxygen, access to mechanical ventilators is limited and medical workers lack personal protective equipment, Serebryannik said.

Testing for Covid-19 is being carried out, but only two or three weeks after sick patients seek care, she said, with the result that they test negative. No antibody tests are being conducted, she added.

Rachel Denber, deputy Europe and Central Asia director at HRW, told CNN the government’s denial of any Covid-19 cases in Turkmenistan was “completely false.”

“The government either has its head in the sand or it’s intentionally being reckless, but the result is the same — the result is mass misery. There’s no policy for acknowledging Covid, there’s no policy for addressing Covid and there are no policies for addressing the food insecurity and poverty that preceded Covid and have only worsened since Covid,” she said.

It is difficult to get information from within Turkmenistan, which has a population of nearly 6 million but no independent media, according to the independent watchdog group Freedom House. But, said Denber, “there have been very significant outbreaks of Covid, and there were times when the numbers of funerals that were happening, according to local sources, were well above what the usual rate is.”

Public health messages promoting measures such as social distancing have been diluted because they are not linked with Covid-19, she said. “Anecdotally, that’s combined with a lot of pressure and intimidation against health workers not to talk about Covid, not to acknowledge that there are cases, not to talk about what they are seeing in their hospitals,” Denber added.

Turkmenistan’s Health Ministry has not yet responded to a CNN request for comment on the presence of Covid-19 in the country.

A Health Ministry statement in January said Turkmenistan was the first country in Central Asia to register Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine against Covid-19.

A WHO team that visited the country last July said Turkmenistan had “not reported any confirmed Covid-19 cases to WHO to date.” But the team’s leader, Dr. Catherine Smallwood, told a briefing that WHO “advises activating critical public health measures in Turkmenistan as if Covid-19 was circulating,” Reuters reported.

In August, WHO voiced concern over a rise in atypical pneumonia cases in Turkmenistan and urged President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov to allow it to conduct independent coronavirus tests in the country.

A 26-year-old man, Nurgeldi Halykov, who reposted an image of the WHO team in the country in July to Turkmen.news, a website based in the Netherlands, was sentenced to four years in prison in September on what the news outlet and Reporters Without Borders said was a trumped-up fraud charge.

Nitzan, the WHO official, said: “While Turkmenistan has not reported any Covid-19 cases to WHO to date, the country has activated measures to prevent the transmission of respiratory infections within communities … Since July 2020, the country also introduced and mandated individual protective measures … and has, at times, implemented restrictive social measures as if Covid-19 was circulating.”

“WHO continues to work closely with government authorities in Turkmenistan with the direct support of its country office to assess health needs and implement actions related to Covid-19,” she said.

North Korea

There are also questions over the accuracy of data reported from North Korea.

A WHO report issued on January 8 this year said that North Korea claimed to have tested 13,257 people and had found no positive cases of Covid-19. The report was based on the data from 15 laboratories in North Korea which the Ministry of Public Health of North Korea provided to the WHO.

No update has been issued since.

North Korea’s priority since the pandemic emerged last year has been keeping the coronavirus from overwhelming its dilapidated health care infrastructure.

Pyongyang voluntarily severed most of its scant ties with the outside world in 2020 to prevent an influx of Covid-19, including cutting off almost all trade with Beijing — an economic lifeline North Korea needs to keep its people from going hungry.

The clampdown on trade pummeled the economy, but from a public health standpoint it appears to have worked. It does not appear that North Korea has suffered through major outbreaks of Covid-19 within its borders. Leader Kim Jong Un has been confident enough to appear in public without wearing a mask on multiple occasions during the pandemic.

North Korea’s isolation may protect it to a degree. But as vaccinations gradually open up the prospect of a return to normal life, the corners of the globe where the virus lingers out of sight will present an ever greater threat.

Fighting Covid-19 is everyone’s responsibility, and diplomatic pressure should be applied to those countries that don’t meet their obligations, said Drobac.

“The longer we let this virus rage anywhere, the more lottery tickets we’re giving the virus to be able to come up with a cool new mutation that’s going to make our lives really difficult,” he said. “It’s not just a potential tragedy for the country’s own people, it’s a risk for all of us.”

By Laura Smith-Spark, CNN