The fourth floor on which writer Mustafa Zikri resides does not keep out the hustle and bustle of Helwan’s streets. We hear the sound of gunshots; Zikri wonders whether people are celebrating a wedding or having a fight. But the sound of popular songs that follows confirms that it is, thankfully, a street wedding.

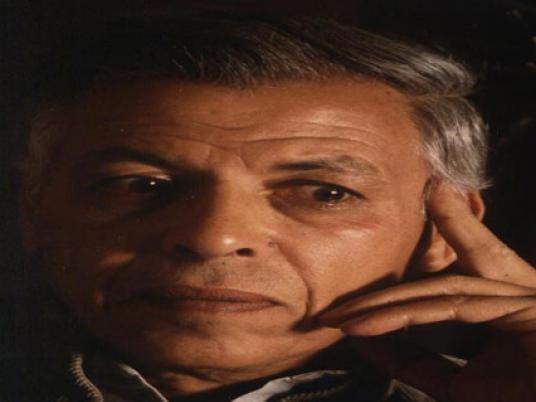

As a writer who lives in isolation — he is rarely seen in the literary salons and cultural cafes of downtown Cairo — few people have met Zikri in person. Still, his thick eyeglasses and bald head, easily recognizable from his photos, make him look familiar and down-to-earth. He comfortably sits in his dimly lit living room with classical Western music playing on his computer.

“I used to listen to many things, including jazz and blues, but that is a thing of the past,” Zikri says. He turns off the music and we start talking.

Zikri, who belongs to the 1990s generation of writers known for their seclusion, has recently released his eighth book. “Hattab Mi’dat Ra’ssy” (The Wood of the Stomach of My Head) is the sequel to his diary published in 2009. The seemingly obscure title is inspired by a sentence found in the book.

Perhaps because of his isolation, you sometimes see Zikri smiling inappropriately or making nervous gestures with his hands. But he is perfectly comfortable when he speaks of things he is passionate about, like “Ulysses” by Irish novelist James Joyce or the writings of Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Zikri explains why he chose that title: “It is an analogy to the energy which operates a steam train. It simultaneously burns out and feeds like my writing. I do not just think about the content of my writing, but I also eat it up.”

Still, the title remains complicated and inconvenient for readers, especially when compared to the title of his earlier diary compilation, “At the Fingertips.”

“I sometimes like to choose strange book titles, like in the case of ‘Drivel About A Gothic Labyrinth,’ but I’m generally not obsessed with titles and use the first one that crosses my mind. I believe the strength of a book will overpower its title,” he says.

Zikri’s writings, which are often very rational and tackle existential questions, have included novels, short stories and two screenplays — “Afarit al-Asfalt” (Devils of the Tarmac), one of the most remarkable screenplays of the 1990s, and “Gannet al-Shayatin” (Fallen Angels’ Paradise), both directed by Osama Fawzi. He is currently working on a third one, which he plans to finish this September, and will also be directed by Fawzi.

“Screenplays are more difficult in writing than literature,” he says. “There are strict rules that I cannot overlook and a dramatic commitment to the characters and film structure.”

Zikri has been away from the silver screen for almost a decade now. It seems that over the years, he has grown fonder of writing diaries.

“I might experiment with different writing styles later,” says Zikri. “But, generally I like the dramatic to come within a philosophical context, rather than stand on its own.”

His diaries are about philosophy, literature, cinema and simple daily happenings that one might overlook. He might analyze a single scene from a movie he admires, or comment on a philosophical theory, or re-formulate film scenes or parts of literary works, like he did with Franz Kafka’s “Wedding Preparations in the Country,” or even an article written by Youssef Rakha about his work.

But compared to the diaries of prominent writers he mentions in his work, like Kafka and Fernando Pessoa, Zikri’s journals seem more deliberate and complex. This premeditation in writing is something he has been unable to overcome.

“I cannot write something if I know or feel it is not for publishing,” says Zikri. “Spontaneity is most characteristic of diary writing, and I lack that completely.”

Zikri’s diaries were published in state-run newspaper Rose al-Youssef and in the Shorfat supplement to the Omani newspaper in 2010 and 2011. “It started as a writing exercise, but turned into the actual writing.”

He usually starts writing when something leaves an impression on him, like a scene from a film, then he moves from that to a saying or value judgment. This could happen in the early morning or after an evening nap. But he often wastes hours before starting, making food or coffee to get himself into the right mood.

He might rewrite two lines in his journal several times before moving to the rest without revising it once. He now types on his computer. But that has taken him a while.

“I had so many restrictions in relation to pen and paper. I had to select a particular type of paper and a specific pen,” he says, showing old drafts where he wrote everything in perfect handwriting. His obsessions made him never cross a word out, but rewrite the whole page if he wanted to make a single edit. The last book he wrote that way was “Mirror 202,” published in 2002 by Dar Merit.

Most of Zikri’s writings are rational. But his life does have a romantic side as well, which might occasionally get reflected in his texts. His 2006 “Rassa’el” (Messages) is one example. A set of messages sent out by the protagonist to his lover, they were influenced by a romantic relationship Zikri had.

“[This was] the time a relationship affected me the most … and influenced my writing,” he explains.

In terms of reading, Zikri does not often acquaint himself with contemporary writings in Egypt; and accordingly, he does not have an opinion about new texts by young writers. Asked how he receives writers who consider him a role model, he responds: “I feel happy that some writers feel that way,” but he gives them nothing.

He recognizes his ungratefulness, accepting their flattering without showing them interest. “I prefer writers who identify with a literary genre or group rather than following the footsteps of a particular author,” he explains.

Although Dostoyevsky was not an avid reader, young writers should read a lot more than they write, says Zikri, “unless they are like Dostoyevsky.” Young writers should follow their literary taste, to be ungrateful to the “norms” of writing, and not fear standing out. They should focus on developing heir style as “the honor of writing is all in its style.”

Despite his devotion to writing and general disengagement with politics over the past decades, on 25 January 2011, Zikri surprised many by writing on his Facebook account: “Down with writing and long live the revolution.” But this moment of optimism and entry into public life did not last very long.

“On that day, that was the utmost sentiment I could express. I believed in what happened, and saw that this is what I can offer,” he says.

He hated the revolution two months later though, he explains, when he felt that it started taking an Islamic turn. This will be reflected on the literary scene as well, he believes. “There would be a questioning of the whole literary genre, and it will take an Islamic turn.”

As for now, “the revolution is gone. We will be like Pakistan in [the] best case [scenario].”

While he is not optimistic about the future of the country, he is content with his own work.

“I’m satisfied with my experience so far. I did what I want[ed]. No restrictions were imposed on me, and I have not submitted to the blackmailing of the profession or the desire to have a large readership or greater fame.”