Manei Mohamed was buying a mobile phone at a kiosk in downtown Arish on the afternoon of 19 May when he suddenly heard gunfire. He looked around and saw a man with his face covered by a scarf run out of a barbershop, hop on a motorbike driven by another masked man, and speed away. When Mohamed entered the barbershop, he found Nayef Abu Qabbal bleeding from his head.

“He was dead by then,” Mohamed says.

Abu Qabbal was a sheikh in the Sawarka tribe, one of North Sinai’s largest and most powerful. Weeks later, who killed the sheikh remains a mystery, but conspiracy theories abound and all come back to the central issues confronting North Sinai: continuing lawlessness, flourishing Islamist militancy, and a precarious and complex relationship between Sinai and the state.

“Talk in the city is that [Abu Qabbal] has a connection with state security and has helped them arrest a lot of people here,” Mohamed says, echoing a view held by many interviewed by Egypt Independent in North Sinai.

The State Security Investigation Services was toppled President Hosni Mubarak’s brutal investigative authority, and was behind the arbitrary arrest of thousands in Sinai on terrorism and smuggling charges.

“We don’t know who killed the sheikh. But the way he was killed shows that it’s probably a vendetta,” says Mohamed al-Menei, a trader from the border town of Rafah, adding that a few of those arbitrarily arrested in Sinai were reportedly identified by security with Abu Qabbal’s help.

Menei purported that it could be a fellow tribesman who killed Abu Qabbal, or a militant Islamist who was arrested and imprisoned thanks to the sheikh’s conspicuous relationship with the security apparatus. He is inclined to believe the second scenario, he says, because “the way the sheikh was killed is not manly.” Citing common tribal practices, Menei says a tribesman would have shot Abu Qabbal in the leg, not the head.

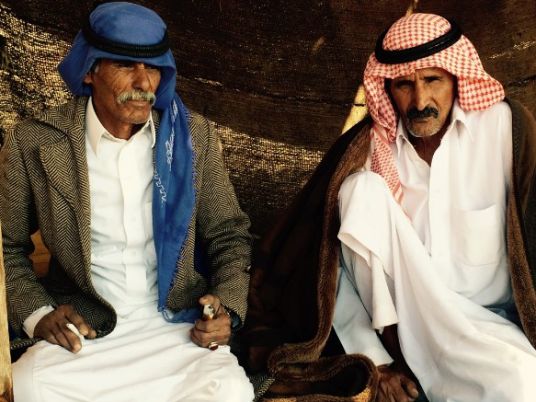

Bedouins of North Sinai have long lamented the co-optation of the sheikh’s position by the ruling regime.

“In the past, the tribe would be the one choosing its sheikh and it would be an informed choice of who can best serve the tribe,” said Moussa Abu Mohamed, a community leader in the village of Mahdeya near the Israeli border.

But during the Mubarak era, sheikhs became an entry point for the central government in Cairo into Sinai’s intricate tribal system.

According to Abu Mohamed and other North Sinai residents, a sheikh is informally pushed to the post through the security directorate and the military intelligence, both active security agencies in North Sinai during the Mubarak era.

“They report to the police and are loyal to state security. The security apparatus has mobilized the sheikhs against the people,” he says.

There are some 150 such sheikhs in North Sinai. They would be the typical interlocutors of the state when a government or a political party claims to establish a dialogue with the people of Sinai.

Abu Mohamed and many other Sinai residents want to see this system changed and a return to the election, or at least the endorsement, of sheikhs by tribe members rather than just the Interior Ministry or the military. While the government relies on its security services and networks of informants to control security threats in Sinai, Abu Mohamed believes a strong tribal system and representative leadership are the real keys to dealing with external threats.

One much-discussed threat these days is that of the new and revived militant Islamist groups operating in the area.

These groups can generally be divided into the more peaceful, proselytizing type and the more violent type. According to various tribesmen, these groups are mainly located in the towns of Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayed.

Al-Tableegh wal Dawah is one such formation, and it’s generally known for being a peaceful group that was founded in the mid-1980s, following the signing of the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel.

Al-Takfeer wal Hijra, a more radical group that is anti-politics, is also commonly cited.

It was born in the late 1970s, when former Muslim Brotherhood member Shokry Mostafa established it as a radical response to President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s execution of the leading Brotherhood figure Sayed Qutb. A reported member of the group in Sinai, Mohamed al-Teehi, was arrested in late 2011 on charges of blowing up the pipeline supplying gas to Israel, but died in prison five months later.

Another group, the Salafiya Jihadiya, includes many of those labeled by the Mubarak regime as “outlaws” and arbitrarily sentenced in absentia to prison on smuggling or terrorism charges, according to many Bedouins. Many of the followers of this group are reportedly less intellectually tied to ideology and more motivated to kill by money.

Many connect the group to the Gaza-based Gaysh al-Islam (Islam’s Army), a splinter of the Palestinian Popular Resistance Committees, which Israel held responsible for the killing of eight citizens in its southern city of Eilat when gunmen crossed over from Sinai last August. Gaysh al-Islam’s founder Mumtaz Daghmash is accused by Egypt of perpetrating several terrorist attacks in Sinai between 2004 and 2006, as well as the 2009 bombing in Cairo’s Hussein tourist area. Accordingly, Egypt has been pressuring Hamas, which controls Gaza, to arrest Daghmash.

The other possible Gaza connection in Sinai is the Jaljalat organization, which was cited by Egyptian security as potentially complicit in the Eilat bombing of August 2011.

But while these groups are met with frenzied anxiety in Cairo-based, Israeli and Western media, locals seem far less concerned.

“I can set up a bar in Sheikh Zuwayed and no one will talk to me,” says Menei confidently.

“Radical Islam in Cairo is one thing and in Sinai is another thing,” says Awad Salman, a sheikh in Massoura village. “In tribal societies, it is hard for militant Islamist ideas to diffuse,” he adds, reiterating that a militant group would fear unruly tribal resistance.

The hype around these groups, he says, is exaggerated. According to Salman, fear of Islamist militants in Sinai is in Israel’s interest, because it gives the Israelis justification for keeping the peace treaty with Egypt unchanged. Salman even takes this idea further, suggesting that these groups in Sinai are manufactured by Israel to create a threat. For evidence, Salman points to a rocket reportedly fired from Sinai into Israel last April, which hit no one. “There are no rockets that can reach that far in Sinai. Plus, why would rockets be launched without targeting anything or anyone?”

Salman’s assessment may sound like a stretch, but many analysts argue that militant groups are often intelligence agencies’ proxies.

“The problem is that we don’t have educated journalists among our sons and daughters to defend us,” he says.

As far as the local following of these groups is concerned, Salman sees an important role for state security, either as a reaction to its arbitrary policies in Sinai or by direct influence.

“When state security [arbitrarily] arrested the men of Sinai and threw them in prisons, we demanded that they would be separated from militant Islamists so that radical thought wouldn’t diffuse. But no one listened,” he says.

Menei, the Rafah trader, has firsthand experience with this phenomenon. His brother was arrested in 2004 and accused of smuggling to Gaza. Those accused of smuggling to Gaza would be put in political prisons alongside terrorism suspects, he says.

“When he came out recently, he grew a beard and joined one of the militant groups,” Menei says, declining to identify which group.

A 26-year-old sympathizer with radical Islamist groups in Sinai who spoke to Egypt Independent on the condition of anonymity shared his experience, as he has just been released from Egyptian political prisons.

“I was randomly arrested in 2006 on smuggling charges and was kept there for four years until charges were dropped following an appeal,” he explains.

In prison, he met several Islamist figures whom he described as “extremely informative.” He came back with this thought: “The Islamists of Sinai are not deeply rooted in one or another ideology. They fluctuate depending on who talks to them.”

He knows one thing for sure: “I just came out and felt unstable. I lost my education and my father died of the pain of losing me.”

Asked whether he would shoot a sheikh accused of working with state security in the foot, according to the tribal tradition, the former prisoner simply says, “Any informer should be liquidated.”