ARISH — For Ahmed Taha, Sharia tribunals are not earthly justice. They come from a higher power.

“The verdict of the Salafi sheikh represents the verdict of God … it must be implemented,” says Taha, a vegetable vendor in North Sinai’s capital city of Arish.

Sharia tribunals are common law judicial proceedings based on Islamic jurisprudence in gathering evidence and issuing verdicts. Following the 25 January revolution, which ousted President Hosni Mubarak, Sharia tribunals have grown in prominence in North Sinai, compared with the more conventional ones, known as “traditional” tribunals.

Official courts of law have never been the standard in North Sinai, where the law of the land has for decades been determined by traditional tribunals or informal reconciliation councils that depend on implementing local traditions and customs.

The state condones these unofficial tribunals, which don’t fall under its jurisdiction, mainly out of pragmatism. Hearings of bigger cases that affect national security are attended by the governor and the head of security in North Sinai.

Tribal judges oversee the tribunals, while the heads of individual tribes are responsible for solving land disputes among members, Sheikh Abdel Kerim Saleh of the Okour tribe says.

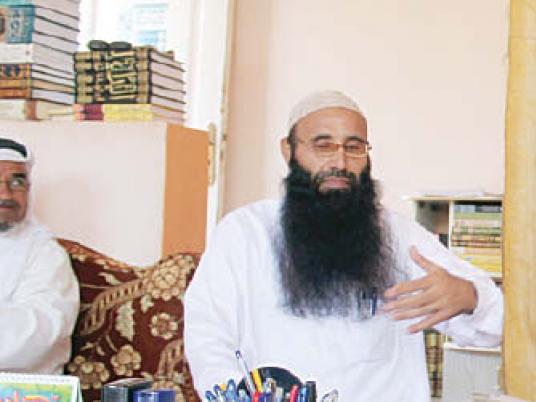

In the increasingly widespread Sharia tribunals, renowned Salafi leaders play the role of judge, such as Sheikh Hamdeen Abu Faisal.

Taha tells Egypt Independent that, in a previous land dispute with a neighbor, Abu Faisal “rightfully” ruled that a plot of land be returned to him. The two parties signed an agreement pledging to implement the verdict.

But the notion that a Salafi leader’s verdicts are sacred is not always sufficient for the losing party in a case. To guarantee the ruling is enforced, Abu Faisal says, the losing party is typically required to leave the lease to their home or land as collateral.

Before the 18-day revolt, Abu Faisal and others conducted rare Sharia tribunals underground to avoid a crackdown by Mubarak’s notorious state security apparatus, which kept a tight grip on Salafis in North Sinai.

Amid the security vacuum resulting from the retreat of police off the streets during the revolt, Abu Faisal says Salafi leaders stepped up to protect the people of North Sinai as well as state institutions, gaining credibility and legitimacy in the process.

While the longstanding traditional tribunals have been marred with accusations of corruption, bribery and favoritism toward the community’s wealthy and powerful, the reputation of Sharia tribunals as keen on implementing the word of God remains intact.

“Traditional tribunals were popular about 20 years ago, when traditions and customs were above everything and the tribal judge’s verdict was [as sharp as] the blade of a sword. … But this has all changed,” Saleh says.

Sheikh Aaref Abu Akar, head of the Okour tribe, says the two types of tribunals work in parallel or are often complementary and not in competition. He adds that the prominent standing of tribal judges and leaders will never be compromised by the surge of Salafis in North Sinai.

“Salafi leaders in North Sinai realize that tribalism is a very strong force there and it’s not very wise to challenge it,”’ says Omar Ashour, director of the Middle East Graduate Studies Program at the University of Exeter Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies.

But there are differences between the two types of common law courts.

In many circumstances, the local traditions and customs upon which traditional tribunals are based are not in compliance with Sharia.

“In traditional tribunals, women, landowners and wealthy parties do not need to bring witnesses to testify on their behalf, while others must have a witness to help them make their case,” explains Abu Faisal.

In Sharia tribunals, all parties are treated equally, and they all have to bring supporting witnesses, he adds.

Residents of Sinai tend to favor Sharia tribunals because they are free of charge and typically speedier, according to Saleh, who has in the past resorted to this common law system to solve a land dispute.

“As long as you’re Muslim, you have to accept the verdict of a Sharia tribunal because it is based on Islamic Sharia, and you cannot appeal it afterward,” he says.

Abu Faisal has also overseen four cases involving Copts. In one land dispute with a Muslim, the tribunal ruled in favor of the Copt as the rightful owner.

Disputes can take as little as an hour or as long as two months to resolve, says Abu Faisal, depending on the intricacy of the case and how much evidence is required to announce a concrete verdict.

In traditional tribunals, an outsider of the area or ordinary resident may need to hire a renowned tribal leader to act as lawyer. In Sharia tribunals, all parties involved can make their own defense, despite their prominence in the tribe or the area.

“I’m from Wadi al-Nil, not Arish, so I need a renowned sheikh who knows the traditions and customs here to represent me in a traditional tribunal,” Taha says, adding that this may cost anywhere between LE2,000 and LE10,000.

Saleh says that in traditional tribunals, a judge can receive a fee of about LE100 from each party. However, according to Abu Faisal, a tribal judge’s fee can climb as high as LE50,000. On the other hand, Sharia tribunals strip out this cost altogether.

Abu Faisal does not have a degree in Islamic jurisprudence from Al-Azhar or any religious institution, but his extensive study on the topic has earned him the community’s respect as a pious scholar.

He is currently overseeing 500 cases through the end of the year, about 75 percent of which used to be handled by traditional tribunals.

He denies that he or other Salafi sheikhs would implement hudud, or fixed punishments for serious crimes as stated in Sharia, such as stoning adulterers or amputating the hands of thieves.

“Hudud represent no more than 5 percent of Islamic Sharia, and they can only be implemented by the state if it chooses to abide by Islamic jurisprudence in its rulings,” he explains.

When it comes to murder, Abu Faisal attempts to rule for monetary compensation, known in Islam as diyah, unless the victim’s family demands retribution. In this instance, the family must take the case to a state court, since sheikhs do not have the authority to implement the death penalty, Abu Faisal says.

The relationship between Salafi groups in North Sinai and the state has for years been characterized by hostility. As attacks on security in the area have increased after the revolt, the state has attempted to tighten its grip, but without much success.

Following the death of 16 border guards shot by armed assailants in August at a checkpoint near Rafah, Salafi leaders in North Sinai met with a presidential delegation this past September.

Abu Faisal says the delegation attempted to improve relations with Salafi sheikhs and ease security concerns.

Abu Faisal and Salafi leader Asaad al-Beik deny claims of the formation of a committee to mediate between the state and Salafis. “We do not know who [the assailants] are or what movement they stem from, so it was not possible to mediate between the two sides,” Abu Faisal says.

More meetings were expected between Salafi leaders and the presidential delegation, but they never took place, according to Abu Faisal.

Salafi leaders say they were willing to assist in maintaining security in the volatile area if the state promised not to sideline or use violence against them.

But this past Sunday, security forces raided seven homes of Salafis in Arish and terrorized their wives and children, detaining two prominent Salafis, he says. One was released and the other was falsely accused of bombing the gas pipeline between Egypt and Israel, which has happened more than 10 times since the revolution.

Abu Faisal says they expected more from President Mohamed Morsy, who rose from the ranks of the Muslim Brotherhood.

According to Ashour, about 70 percent of North Sinai residents voted for Morsy in the presidential election in hopes that there would be a new sense of cooperation to replace their being ostracized under the former regime.

And despite violations against Salafis by incumbent security forces, he adds, they are much more tolerant than Mubarak’s apparatus.

“Salafis hope to open a new page with the state and achieve reconciliation after decades of being subjected to security crackdowns,” he says.

While the region at times seems autonomous, the state is still very much in the picture.

The security directorate and military intelligence are involved in appointing tribal leaders in the area, Abu Akar says. Tribesmen elect three candidates who are presented to the security directorate and the military intelligence, who make the final choice and appoint the leader of the tribe.

Since Salafi leaders are not linked to the state, Sharia tribunals are perceived to be more independent.

“Now, people are free to decide which sheikh is credible and worthy of solving their disputes away from the state,” Abu Faisal says.