Over the past half century, prolific writer Anis Mansour established his name among those of the nation’s key cultural figures.

Mansour passed away on 21 October at the age of 87, leaving a legacy of more than 185 books that he had written, edited or translated. He wrote on various topics, from travel and science to biography, philosophy and politics. He was the first Arab journalist to interview significant international figures such as the Dalai Lama, and one of the few who wrote about supernatural forces. This garnered him wide popularity, with some of his books reprinted more than 30 times. But it was young readers that Mansour particularly appealed to, earning the label "the youth writer.”

For Mohamed Badawy, a professor of Arabic literature at Cairo University, Mansour provided Arabic readers with high quality translations. Badawy cites Mansour’s translation of Swiss dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s 1956 tragicomic play “The Visit” to show that he was not a mere translator, but rather “an artist in writing.”

And indeed, Mansour’s accessible and attractive writing style, which favors the sensationalism and picturesqueness of literature over journalistic writing, is what made him particularly unique. The intellectual rigor of his writings, however, has been widely contested. His popular views on existentialism were deemed overtly simple, the travelogues at times stereotypical, and his commentary on women’s conditions occasionally sexist.

Starting points

Born in 1924, Mansour studied philosophy at Cairo University. Upon graduating in 1947, he started his writing career by translating short stories under various pseudonyms.

After the 1952 revolution when the Free Officers’ Movement seized power, the widely read weekly magazine Rose al-Youssef commissioned Mansour to travel to Europe to follow news about the deposed King Farouk. Writing under a female pseudonym, Mansour wrote about the king’s travels, lifestyle and visitors. Rose al-Youssef, which had not been nationalized yet, spearheaded a campaign against Farouk based on the loss of the 1948 war, which is argued to have been the result of the Egyptian army's surfeit of defective weapons.

But it was Mansour’s travelogues that launched his career. Inspired by Jules Verne’s 19th century classic “Around the World in Eighty Days,” Mansour embarked on a journey around the world in 1959.

For 225 days, he traveled across the continents, meeting some of the most influential figures internationally. His dispatches from Asia, America and Australia – he’s claimed to be the first Arab journalist to visit the continent – were published in the widely distributed Akhbar al-Youm. The dispatches were exciting, and at times humorous. They nevertheless offered few insights on the countries he visited and at times reinforced stereotypes.

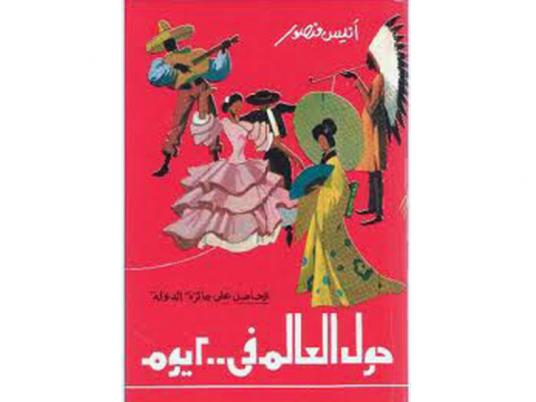

Mansour later compiled the dispatches in his 1963 book “Around the World in 200 Days,” for which he received a major state award.

Today's readers of “Around the World in 200 Days," however, will only enjoy its witty writing style. The book mostly reflects general impressions. Writing about India, Mansour described the country with phrases such as: “India is a nation where tea is the dominant drink … and some Indians don’t eat meat.”

Initially the purpose of Mansour’s journey was to write a story about the Indian state Kerala after the communist-led government was elected 1957, and to meet the Dalai Lama.

When the Tibetan spiritual leader declined to meet him at first, Mansour’s reaction was offensive. He wrote: “Shame on you Dalai Lama, shame on those who made you a God. They are a bunch of animals that deserve a foolish guy like you.” Even when he managed to meet the Dalai Lama, the interview offered no real insights.

Still, “Around the World in 200 Days” has been reprinted more than 25 times to date, and Egypt’s legendary intellectual Taha Hussein wrote the introduction of its third edition, praising Mansour’s style.

He did however highlight that Mansour’s views on China were solely based on his visit to Hong Kong. Mansour had not been to significant parts of Asia, such as Turkey and Central Asia, according to Hussein.

The youth writer

Mansour’s attractive writing style could be easily compared to some of his contemporaries, notably leading journalists Mostafa Amin (1914-1997) and Mohamed Hassanein Heikal (1923). But in the 1960s, writers were pushing for incorporating a strong political voice, which Mansour abstained from. He chose rather to write about unconventional themes such as space science, simplified philosophical ideas and life abroad, which appealed to young Egyptians.

His novel “Who Would Not Love Fatima?”, which was turned into a TV series in 1993, caused much controversy when an Egyptian expat in Austria filed a lawsuit against Mansour, accusing him of plagiarism. The novel was about an Egyptian who travels to Austria, where he marries an Austrian woman who converts to Islam and calls herself Fatima.

His popular translation of Michael Hart’s 1978 book “The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History,” was also downplayed by some critics. In the translation, Mansour removed paragraphs and presented his views on the selection as part of the original text.

Still, Mansour’s popularity continued to grow. Egyptian universities invited him to lecture; the Ministry of Education included many of his books in public high school libraries; and he was hired as editor in chief of some of Egypt’s bestselling magazines in the 1960s, such as “Al-Geel” (The Generation) and the women’s magazine “Hiya” (Her). But when Mansour was nominated to succeed the late literary critic Ghali Shoukry as head of the cultural magazine “Al-Qahira” (Cairo) in the 1990s, notable intellectuals including the critic Abdel Rahman Ouf campaigned against it, calling Mansour “the myth writer.” Critics accused Mansour of presenting myths as scientific facts, citing two of his bestselling books, “Those Who Came From the Sky” and “Those Who Returned to the Sky,” which discussed occurences of people and creatures allegedly going to or coming from outer space.

Politics

Mansour rarely discussed politics overtly, yet his writings, often situated in a socio-cultural context, reflected his relationship with Egypt’s various ruling regimes. Under Gamal Abdel Nasser, Mansour hailed the president as a liberator and great leader. But upon Nasser’s death, he launched a fierce campaign against the nationalist president, criticizing his despotic rule, and became strongly aligned with late President Anwar Sadat. Many political commentators believe that he had an influence over the president. He was a member of the delegation that accompanied Sadat on his much-contested visit to Israel in 1977.

Under Hosni Mubarak, Mansour received the state’s most prestigious awards in 1981 and 2000, and was member of the Shura Council for more than two decades. The writer was a vocal supporter of the regime’s crackdown on militant Islamists in the 1990s, and this January he chose a middling position. He wrote in support of the Mubarak regime, dismissing similarities between Tunisia and Egypt, arguing that the latter enjoyed civil liberties, while simultaneously praising the revolutionary youth who marched to Tahrir Square demanding freedom.