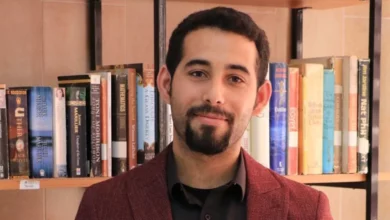

Maged Zaher’s latest collection of poems, “The Revolution Happened and You Didn’t Call Me,” is a slim, postcard-shaped volume of very short poems. The collection follows Zaher’s travels between Cairo and Seattle between July 2011 and February 2012.

On each page, stanzas are framed by a pair of faintly dotted diagonal lines, as though the sheets could be gently torn out and sent in the mail.

The collection — Zaher’s third — opens with a two-line poem from Seattle. Here, the poet is leaving home in the summer of 2011 and returning to Cairo, the city of his birth. Zaher’s Cairo is both “a city under deconstruction” and, later, a city “under heavy rebranding.” Things are changing here, although we are not entirely sure how, why or to what end.

But where the city is headed is not one of the volume’s core concerns. Instead, it is more interested in the meaning of each individual moment. Many creative works have taken “the revolution” or ensuing social upheavals as their fodder. Most become quickly outdated: after a month or two, the views expressed within seem to be from another era, or even another planet.

Zaher’s poems escape this by juxtaposing the moment not against its imagined place in a linear history, but against itself.

The poems are exceptionally short, most not more than four or five lines. This brevity was, Zaher says, required by the moment.

“I was always interested in the short form,” Zaher says via email. “One of the poets I admire a lot is the Japanese haiku-ist Hosai Osaki. That said, I didn’t expect to write short poems myself. But at the moment I started doing so, I almost had to, since I was very tired, in the sense [that] I had energy only to write short poems. So in a way, it all happened by chance.”

He found the style worked well for him.

“Later I found that I enjoyed the short form a lot — it worked well in capturing one thing and one thing only, and it gave me a chance to make movement between poems instead of between lines.”

Indeed, it is the space between the poems that does a lot of the collection’s work. Each poem is spare and untitled. The intense, minimalist focus gives the collection a gallery-like feel: It is as though we are walking through the poems, taking a moment to smell and taste each one — and to recall our own similar experiences — before we move on. There are a lot of pauses here and many leaps of faith, as though every Cairo moment requires turning the page into some new unknown.

From the summer of 2011:

Inside the square, a gondola/We are on a coffee break

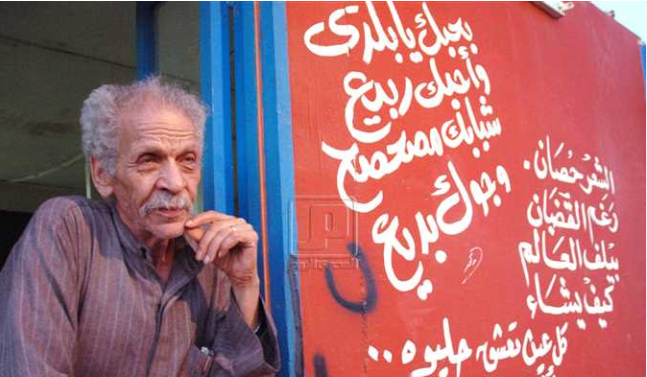

While the prosecution presents its case: “Sir, I’m here” — the journalists are jetlagged/ And the graffiti artists are carrying the burden

And then, on the next page:

Browsing comments about the riot police’s patriotic violence —/We are the remaining communists/ In a postmodern version of everything

Even in their abstractions, the poems have an intimate, narrative quality. Events are foregrounded, but they are never placed in a trajectory where one thing logically follows another. Instead, they follow their own personal logic: It is Cairo /So I am up all night /Texting flawed translations

The collection’s main section paints a particular picture of Zaher’s times in Cairo. He spends his time with “quality nihilists,” the fashion-conscious old left, anarchists, remaining communists, and tea makers. He often thinks about his privilege and “class struggle all the time,” but he is equally interested in how his nostalgia colors his relationship to Cairo.

Images often surface and resurface in different forms; many of them evoke specific memories from Cairo’s summer of 2011: Intense window-or-aisle politics/Counter-revolution road rage/And its promised piecemeal luxury

Other poems give a more general feel of the city and could have been written in 2011 or 2001.

This is Cairo, so humor also bubbles up often: Biting into a prolonged nostalgia/There are well-meaning CIA operatives around/ And they mostly train kind assassins/ Oh love, oh careless love

“The short form allowed me to try different things,” Zaher said, adding that his relationship with the form developed over time. Some of the shortest poems have a lovely, aphoristic quality and are not unlike haiku: A cup of tea is an elaborate world —/And it takes time to dig oneself out.

After the section dated mid-July 2011 to the end of September 2011, Zaher returns to Seattle. Here, the narrative is “in between historical events,” and the world is much lonelier, less vividly realized.

Seattle is less concrete than Cairo and much more forgettable. It is a place where: “If you follow the attached link/The state will happily deliver its violence to your computer screen.”

The collection ends with “a second Cairo trip, etc.” in February 2012. Here, the landscape has changed from the earlier section. Cairo has grown more unsteady; there is more violence and less optimism. One poem says, “There are bearded men/And lovers/Walking to McDonald’s/(The one next to the armored vehicle).”

Humor is still a refuge: Surrounded by judgmental cops/And fear of imagined violence/Puns help a little/As I am watching the world go digital

At the book’s end, nameless people are using “electoral maps to plot the next move” — whatever that might be. There are important things to be considered, regarding Cairo’s future and the upcoming elections. However, these concerns “escape me now/But they can be shelved for a future poem.” The last page in the book moves to a space beyond politics, to an elevated longing.

Airport hallucinations

An exclusive excerpt from Zaher’s "The Revolution Happened and You Didn’t Call Me":

“I will be your terrorist today” the poet said to the pilot on their terminal to terminal train. The pilot smiled, and said that he was contemplating suicide few hours earlier from the top of a pointless Seattle monument.

We eventually discussed death; the irreversible damages that happen to the body before it arrives. We competed describing one’s father’s lung cancer and the other accompanying his uncle’s corpse to the dead bodies washing room. Later, I left him and went to the ticket counter to get my next flight boarding pass. It was time to go to other airplanes to talk to other people about similar things.

The transit city feels rugged, people on bikes had expressionless expressions, this is when I decided to enter the bookstore and give them a book as a gift. I told many people that to have been raised on socialist realism meant that I had a longer recovery path.

I am not looking forward to Cairo, the new regime businessmen in their pretend smug piousness are scavenging the dead corpse of the city stricken by insane poverty with the same viciousness of their predecessors. The revolution is tired and feels like far history.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.