More Americans with diabetes will get a break on their insulin costs in 2024.

Sanofi is joining the nation’s two other major insulin manufacturers in offering either price caps or savings programs that lower the cost of the drugs to $35 for many patients. The three drugmakers are also drastically lowering the list prices for their products.

The moves were announced in the spring, but some didn’t take effect until January 1.

Drugmakers have come under fire for years for steeply raising the price of insulin, which is relatively inexpensive to produce. The inflation-adjusted cost of the medication has increased 24 percent between 2017 and 2022, and spending on insulin has tripled in the past decade to $22.3 billion in 2022, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Some 8.4 million Americans rely on insulin to survive, and as many as 1 in 4 patients have been unable to afford their medicine, leading them to ration doses – sometimes with fatal ramifications, according to the association.

Congress, the White House and new players in the market have increased pressure on insulin manufacturers to lower their prices. Eli Lilly and Sanofi announced that they would institute $35 caps shortly after President Joe Biden called on drugmakers to do so in his State of the Union address last year.

Medicare enrollees now pay no more than $35 a month for each of their insulin prescriptions, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, which Democratic lawmakers pushed through Congress in 2022.

But drugmakers also faced changes to the Medicaid rebate program that would have likely cost them hundreds of millions of dollars each if they didn’t lower their list prices.

$35 price cap

Sanofi established a $35 monthly cap on out-of-pocket costs for Lantus, its most widely prescribed insulin in the US, for all patients with commercial insurance starting January 1. It already limits the cost to $35 for all uninsured patients.

Novo Nordisk in September launched the MyInsulinRx program, which provides a 30-day supply of insulin for $35 to eligible patients, including the uninsured. The company also offers a copay savings card that allows eligible patients to buy its insulin products for as little as $35 and no more than $99, depending on their health insurance coverage.

And Eli Lilly in March instituted an automatic $35 monthly cap on out-of-pocket costs for those with commercial insurance buying its insulin products at participating retail pharmacies. The uninsured are able to download the Lilly Insulin Value Program savings card, which allows them to get the medication for $35 a month.

Insulin makers are more willing to cap out-of-pocket costs now because of the public pressure to increase affordability and because of new competitors, such as Civica Rx, said Tim Lash, president of West Health Policy Center, which focuses on lowering the cost of health care. Civica Rx is working on manufacturing and selling insulin for no more than $30 a vial.

The caps will also help the three companies cement their relationships with their patients.

“The amount of profit that they might be giving up [by capping costs] is relatively limited,” Lash said. “The goodwill that they get is very significant.”

Saving millions in Medicaid rebates

All three companies are also lowering the list prices for many of their insulin products, which lawmakers and patient advocates have pushed for for years.

Sanofi cut the list price of Lantus by 78 percent to $96 for the prefilled pens and $64 for the 10-milliliter vial starting January 1. It reduced the list price of its short-acting Apidra insulin by 70 percent.

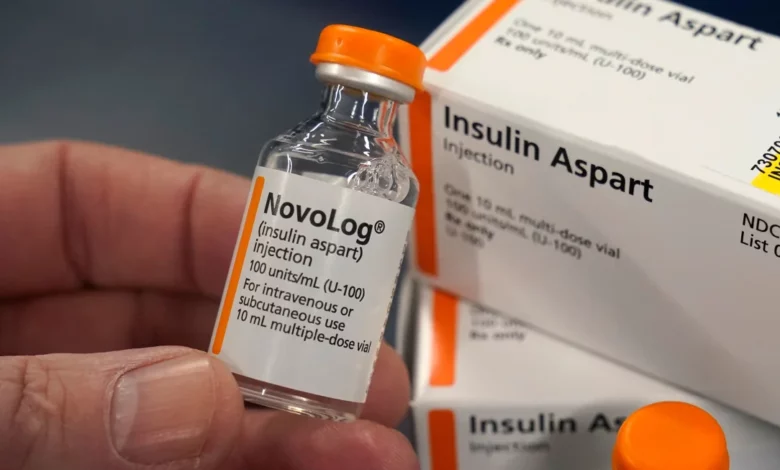

Novo Nordisk lowered the list prices of several of its insulin vials and prefilled pens, including NovoLog, Novolin and Levemir, by up to 75 percent as of January 1. The new list price for NovoLog is $72 per vial and $140 for the FlexPen.

And Eli Lilly said it would slash the list prices of Humalog, its most commonly prescribed insulin, and of Humulin by 70 percent by the end of 2023. Humalog will now carry a list price of $66 per vial.

These moves were carefully timed and will save the companies hundreds of millions of dollars a year, experts said. That’s because the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act made a major change to the rebates that drug manufacturers pay annually to state Medicaid programs – a change that kicked in on January 1.

The rebate is based on how much a drug’s list price has increased compared with inflation and how deeply it is discounted in the commercial market. Until now, that rebate was capped at 100 percent of the drug’s average manufacturer’s price, which is a proxy for its list price.

But that cap disappeared on January 1, so the rebate could now be larger than the amount the drugmaker earns from Medicaid for the medication. About 15 percent to 20 percent of brand drugs have reached the cap, according to IQVIA, an analytics and research company.

By cutting the list prices for Humalog and Humulin, Eli Lilly could avoid having to pay an additional $430 million in Medicaid rebates in 2024, said Spencer Perlman, director of health care research at Veda Partners, a consulting group that provides policy analysis to institutional investors. Plus, Eli Lilly could earn an additional $85 million in profits from Medicaid because of the way the rebate formula is designed.

Novo Nordisk could avoid about $350 million in new rebates and earn nearly $210 million more on NovoLog and Levemir. Sanofi, meanwhile, could avoid $560 million in rebates and earn an additional $200 million in profit on Lantus.

Asked for a response about the Medicaid rebate payments, Novo Nordisk said changes in price trigger several operational requirements and affect multiple parts of the company, which is why it implemented them on January 1.

Sanofi said it reviews its pricing and access strategies to balance patient affordability with enabling the company to continue to invest in innovation.

Eli Lilly responded that it weighed multiple factors – including changes in the marketplace, legislation and regulations – to determine the right time to lower list prices in a way that is affordable for patients and ensures that the company can continue operating a sustainable insulin business that can keep providing the drug to Medicaid at little to no cost.

Drugmakers would have been hit so hard because they all hiked the list prices of their insulin, and they provide hefty rebates to pharmacy benefit managers to ensure their products are covered by insurance plans.

“Before the price cuts, these older insulin products were multitudes higher from a pricing perspective than they were 30 years ago when they were first launched, and they were highly rebated,” Perlman said.

This story has been updated with additional information.