I learnt a new word the other day: “stratocracy.” That’s a ruling system where the state is ruled directly by the military. Apparently, it’s rather different from a military dictatorship, where power merely resides with the military.

I might be hazy on the distinction but I don’t think I’m having too much trouble assessing the current situation. The military holds the reins and it shows no signs of giving them over to any other drivers any time soon. It’s not that I suspect that the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) want to remain in power for ever. They merely want to consolidate their power completely. The army does not trust, nor has it ever trusted, civilians to take those reins, and anybody who thought otherwise must be suffering something of a rude awakening now.

When former President Hosni Mubarak stepped down in February of this year, he ostensibly ceded power to the army. In actual fact, it’s almost certain that it was the army that took the final decision and asked him, politely, to step aside. The events of the last nine months have been so momentous that people forget a basic fact: the military has ruled this country for over 60 years. Hosni Mubarak, much like Anwar Sadat before him and Gamal Abd El-Nasser before him, were the customer service section of the military. Of course, regardless of how one feels about them, Sadat and — even more so — Nasser, were leaders in their own, indisputable rights, but they were still military men. However, removed from the everyday stench of corruption and abuse, the army remained above the fray. During the decades of war, Egyptians always held the army in high regard, and that regard carried over into peacetime. And when it supported the 25 January revolution, the army effectively purged itself of any wrongdoing, stepping forward to safeguard Egypt’s people and her institutions.

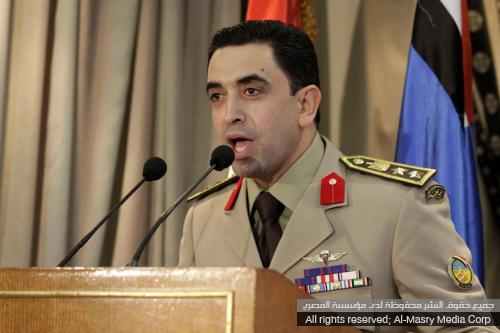

On 12 February, the day after Mubarak stepped down from — or was shoved off — his pedestal, a SCAF spokesman saluted the martyrs of the revolution (the first time the military had ever saluted civilians) and pledged to oversee the transition to a civilian government elected by the people. The timeline suggested was six months, which struck many as somewhat unrealistic. The idea was that they would help usher in parliamentary elections, followed by presidential ones. Somewhere in between, a constitution was to be re-written, guided by the results of a referendum on amendments to the 1971 Constitution, to be held in March.

The problems started when the SCAF assigned the writing of those constitutional amendments to a committee that it had hand-picked without any reference to anyone else. At no point did the army provide a plan B — what would happen if the people of Egypt said they did not approve those amendments. At any rate, they were approved by a resounding 77 percent of the vote. At the time, the SCAF made an announcement to quash rumors about delaying the presidential elections until 2012.

Seven months later, the SCAF imposed a new timetable, with presidential elections possibly to be held as late as mid-2013.

During the course of those past nine months, there has been a gradual erosion of national confidence in the army. It was slow, at first: a constitutional declaration that followed hot on the heels of the referendum; a staggering rise in the number of military trials for civilians – an estimated 12,000 so far, almost four times the number under the former regime; increasing allegations of torture by army personnel; the harassment and censorship of journalists critical of SCAF; a refusal to lift the Emergency Law, despite earlier promises to do so.

Three weeks ago, during a demonstration by several thousand Copts protesting the burning of yet another church, a mêlée of violence left 28 dead, many crushed under a military armored personnel carrier, which appeared to actively chase them down, a soldier firing an automatic firearm from its turret. The army, which had promised that it would never raise a hand against Egyptian civilians, appeared to have broken that promise. In a press conference several days later, two SCAF members insisted that it had not been the army that was shooting, because its soldiers “carried no live ammunition.” The army regretted the loss of life profoundly, the generals said. But they did not apologize. An apology carries an implicit admission of responsibility, and that, they said, lay at the door of violent protestors, fifth columnist instigators, and the always-popular “foreign hand.” In other words, the responsibility was anyone’s but their own. The incident, one of the worst instances of public violence in the country’s recent history, indicated, at the very least, a startling incompetence.

Months ago, the creeping worries could be allayed by telling ourselves that it wasn’t that the SCAF had any ulterior motives; they were simply new to civil administration. They were, to put it kindly, bunglers, not power-seekers. However, at this point in time, several things have become clear. The army has no desire for rapid, expansive, change. Far from it. It fared well under the old system and it needs to tread very carefully to check that this new democracy lark doesn’t upset its apple cart. That translates into deliberately sluggish policies, constantly mulled over by a puppet government that appears largely incapable of taking any decisions on its own.

To complicate matters, the SCAF appears to court favourites among the political parties. Indeed, it often behaves much like a political power itself, dividing to conquer. Nor does it have to suffer the irritating drawback of having to please its party or any constituency. It pleases itself. And the leading political parties have all played into the SCAF’s hands, squabbling over electoral issues while ignoring the most problematic issue: holding the SCAF to a timeline detailing the transfer of power.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who’s paid attention to the army, discreet though it has always been. The protection it offers has always been heavily laced with condescension. The combination of an honest need to protect the country from incompetent civilian bunglers and the need to maintain power produce a powerful motive to delay any transfer of authority.

All this begs the question: now what? The army’s ascension to power was legitimate and the way it relinquishes it must be equally legitimate. The March amendments covered the presidency, and it is easier to hold new presidential elections than have the country leaderless until a constitution is written. More to the point, that constitution must ensure that once a civilian administration takes power, it may not be tossed aside by the military. Egypt’s new constitution must be written quickly and it must be written without any military preconditions. The army may be the supreme protector, but it is not supreme. It is an institution that serves this country, much like the judiciary and the police. That means it must be accountable. Exceptionalism was the rule under the old order. It has no place in the new one.

Mirette F. Mabrouk is a Nonresident Fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at The Brookings Institution.