There is something definitely strange about Egyptian politics.

Opposition parties decide to participate in elections, even though they know from experience that they will be rigged. Having decided to fight for scraps–or, perhaps, for the nobler goal of bearing witness to the fraud they are victims of–these opposition candidates then become indignant when they realize that the elections are not being rigged their way, or are rigged more than was expected.

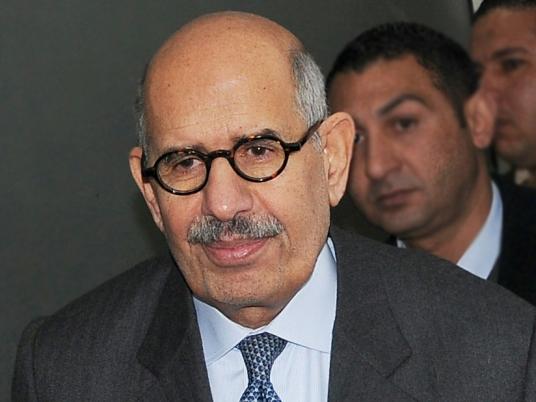

These parties then decided to stage a boycott, only a few months after rejecting earlier boycott proposals–essentially boycotting of an event that has already taken place. Kudos here to Mohamed ElBaradei’s principled opposition to participating in elections under the current political climate, which made a lot more sense–both logically and politically.

The opposition movements, denied a presence in a parliament in which they would not have any power or influence on legislation, then decided to create a shadow parliament, whose power would be even less tangible and whose legitimacy even more flawed than the real one. What kind of parliament, after all, appoints itself without any election at all?

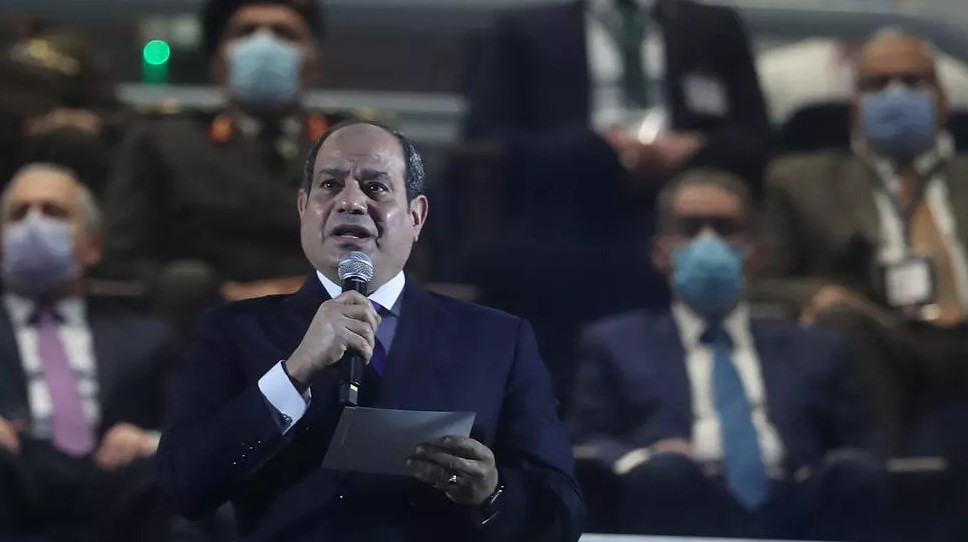

No wonder President Hosni Mubarak could easily quip, during his recent inauguration of the incoming parliament, that the shadow MPs were welcome to have their fun.

But to be fair, there is also something strange about the president’s speech.

One would think that a country in which the ruling party secures 93 percent of seats in a parliamentary election universally seen as fraudulent might acknowledge that there was a problem.

When a country’s most respected judges announce they want nothing further to do with election monitoring, since their court rulings and monitoring reports are simply ignored, it might be time to listen.

When legal scholars point out that the last three elections could very well be illegal–along with the legislation these elected parliaments have produced–it might be time to change the way things are done.

While parliament and the judiciary are of doubtless importance, it might be time to finally acknowledge that checks and balances between the branches of Egypt’s government are not only uneven, but non-existent. The executive not only dominates, but acts in a predatory manner against the other branches.

Rather than maintain the illusion of a country run according to a constitution, with laws written and enacted by a representative parliament, where courts ensure that those laws are enforced, the opposition now has a golden opportunity to stop going along with this charade.

Mubarak chose to devote most of his speech to the new assembly to proposed legislation to drive further economic reform. There are bills that aim to overhaul health insurance, make mortgages available to a much wider segment of society, regulate water usage, ensure internal markets work correctly, and a whole lot more.

If you were to look at the spate of reforms planned for the next few years, along with those of the last few–over which, incidentally, neither ruling party or opposition MPs had much of a say–you would realize that an epochal change is coming to Egypt. For the first two decades of his rule, Mubarak blocked these changes. Now, however, they appear set to become one of the biggest parts of his legacy.

Political reform, however, won’t be. It’s now clear, and should have been a long time ago, that this was never something Mubarak was interested in.

For much of the past decade, the opposition that managed to get into parliament–the Wafd, Ghad, Tagammu and Nasserist parties, as well as the Muslim Brotherhood–fought over seats at a table at which they had no say, while laws were being drafted elsewhere.

The temptation for these parties is to wait things out–eventually, there will be a new president, and perhaps new opportunities. But they could also focus on a single cause–a project that promised to unite leftists, Islamists, liberals and everyone else. At a time when they appear adrift, a simple unifying project might be just what’s needed to transcend the institutional façade, without pretending that parliament is a working institution or that court rulings matter.

I would choose something both grand and simple. I would campaign the president–clearly the only person that matters–to put an end to police brutality. It doesn’t necessarily need to be about ending the Emergency Law (although Mubarak had promised to do just that in 2005), or carrying out ElBaradei’s seven points for reform, as worthwhile as these are.

The campaign would be about asking the chief executive to give the order, clearly and publicly, that police must be held accountable for their actions and that torture must stop. I wouldn’t expect an overnight miracle, but this tactic has worked before in other countries.

Morocco under King Hassan II had been notorious for torture and political detention even worse than Egypt’s. But in the 1990s, as his reign came to an end, he realized that things had to change and began preparing his legacy. Political prisoners were released, secret prisons were closed, and torture largely stopped. This does not mean that Morocco became a democracy, but at least it became a country in which the public did not live in fear of government officials and had a little more trust in the state.

Mubarak might just be convinced that his legacy should involve more than stability and economic growth.

You could call it the Khaled Saeed project.

Issandr El Amrani is a writer on Middle Eastern affairs. He blogs at www.arabist.net. His column appears every Tuesday.