More must be done to understand the ecological roots of the spread of bird flu in Egypt, an epidemic that has one of the highest rates of infection in the country yet, experts on the illness say.

The government is set to launch another nationwide campaign to halt the spread of H5N1 avian influenza, according to the Integrated Regional Information Networks, an independent news service of the UN. Few details of the campaign have been announced, but it will offer awareness programs in rural areas and incentives for the poultry industry to check for and report illnesses in their animals.

While educating those most at risk is important, experts say the government must focus more attention on understanding the roots of bird flu.

So far, research has focused on a “genetic component,” said Basma Sheta, a PhD student at Mansoura University who is researching the virus. “But what about the origin and migratory birds, if they are the main hosts? There’s no ecological view in Egypt, it’s not studied, so we need to start talking about the ecological aspects of this information.”

Indeed, little is known about where the H5N1 virus has hit, aside from large-scale poultry producers.

“There’s no database because people are simply housing ducks and chickens in the backyards; right now we just have an idea of poultry for main producers, not backyards,” said Sheta.

When the first documented infection appeared here in 2006, researchers thought it had been carried by migrating birds. Of Egypt’s 470 bird species, 320 are migratory, traveling four different paths.

But Watter Al Bahry, a bird enthusiast and wildlife photographer, dismisses the claim, saying that no migrating bird has been found carrying the illness thus far. It’s more likely, he said, that the H5N1 virus entered the country from farms in Europe or China, which supply chicks to Egypt.

“Some wild birds died because of sewage from affected farms dumped at breeding habitats,” said Bahry.

According to IRIN, the campaign will involve coordination between the Health and Agriculture ministries and poultry producers. The government will create incentives for poultry growers to report illnesses in their animals.

While targeting breeding and poultry farms is a good step, Sheta said it is equally important to reach rural areas, where many keep backyard animals as a source of income and protein.

“All recent cases [of bird flu] come from rural areas … so you need to speak with them. We’re working on that now,” said Sheta.

“Egypt is a migratory station for birds coming from Europe and Asia. Big numbers of birds migrate through, so that could be one factor and then the second may play to cultural traditions and customs that affect transmission.”

Most of the victims in Egypt have been young girls or women, who are generally in charge of looking after poultry in rural areas.

“In rural areas, ducks and chickens live in close areas, children may play amongst the poultry or women may be in the kennel and a few meters away is a dead bird,” she said.

The Health Ministry campaign comes after the ministry confirmed last month two cases of humans infected with bird flu.

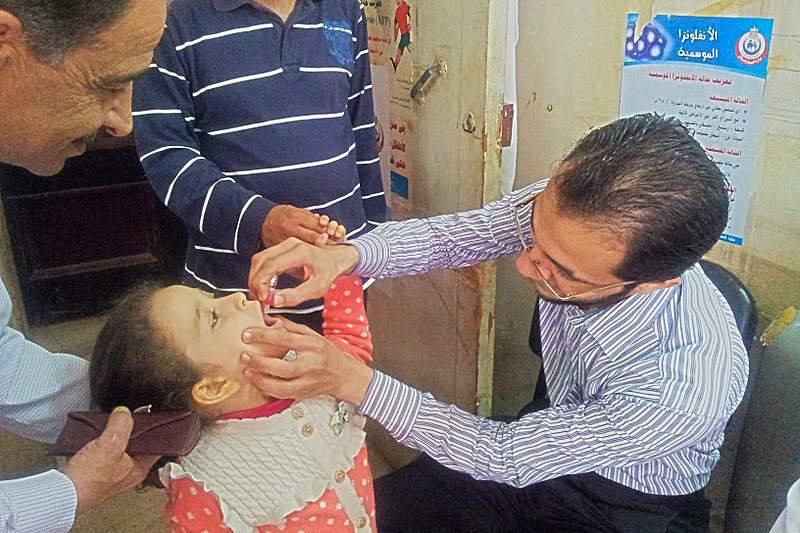

According to the World Health Organization, a 2-year-old girl from Cairo was diagnosed with avian influenza after being exposed to backyard poultry.

A 31-year-old man from Fayoum who was also exposed to privately owned poultry tested positive for the virus.

In rural areas, birds including chickens and ducks are traditionally raised on rooftops, often in close proximity to young children.

Last year saw 39 reported cases, the highest number of H5N1 infections in Egypt in one year, according to WHO statistics. The organization reported 15 deaths from bird flu in 2011, also the highest in Egypt’s history. Egypt has the world’s second-highest H5N1 case count behind Indonesia, and third-highest fatality total after Vietnam and Indonesia.

Bird flu, at present, is not easily transmittable. The virus usually infects people who have come in direct contact with diseased birds. The government took measures to stop infections in 2010, including banning poultry from being transported across governorates, and increasing pressure on poultry breeders to keep animals healthy.

But Sheta said more needs to be done. Of the 159 cases confirmed to date in Egypt, 55 have been fatal, according to WHO.

Sheta said efforts must be placed on developing technology and tracking the virus.

“The medical vaccination has not yet been developed effectively, and in rural habitats you have no control,” Sheta said.

There have been 342 human deaths worldwide from 581 confirmed bird flu cases since 2003, WHO has reported.