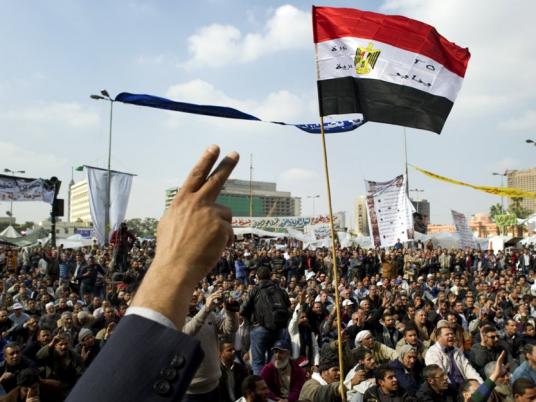

The first presidential election following a popular uprising celebrated for giving Egyptians their voice back is not as glorious and exciting as it was expected to be. Instead, it’s marked by fear and disappointment.

Having learned throughout the last year and a half that there’s no room for dreamy revolutionary aspirations in the world of electoral politics, most people seem to be choosing their candidate out of fear of the alternatives rather than conviction in their choices.

A few days ahead of the big day, a dozen voters from different backgrounds and political inclinations interviewed by Egypt Independent all said that they were choosing “the least bad” option from among the candidates.

“It’s a historic event but its joy was spoiled ever since the parliamentary elections. They taught us that nothing good comes out of elections,” says Zeinab Saad, an engineer.

Saad will vote for former Arab League chief Amr Moussa out of fear of Islamist domination of politics. “It’s not like I’m a fan of Amr Moussa,” she says, expressing a widespread feeling among voters that, with no ideal candidate, they could only choose by elimination.

For housewife Mai Saad, the prospect of an Islamist president is so horrifying that she would rather have no election at all. “I wish that something would happen and the military takes over power; this would be the best option,” she says.

Egyptians approached the parliamentary elections late last year with more enthusiasm. But then they learned the hard way that democratic elections alone are not enough to solve the country’s problems.

An Islamist-dominated Parliament has disappointed those who elected it by occupying itself with trivial arguments and failing to solve any of the people’s most pressing problems.

Meanwhile, problems that resulted from the turbulence of the revolution persist, such as a deteriorating economy, rising crime, and frequent violent outbursts. No advances have been made regarding chronic problems such as poverty, unemployment and illiteracy.

The reignited interest in politics is hanging on by a thread for the majority of Egyptians, who find themselves still living in dire conditions a year and a half following the revolution. Putting politics aside, Mohamed El Kennawy, a 65-year-old doorman, says all he wants is for someone to bring justice.

“The poor people have been buried alive for so many years. We only want someone who’s just to rule us,” says El Kennawy, “I don’t care who comes as long as things will calm down.”

As for those making their choice with the interests of the revolution as their first priority, the election is far from satisfying.

Many have found themselves forced to give up their ideological preferences in order to choose the candidate who can compete with figures from the former regime and Islamist candidates.

The strongest candidates supported by the revolutionary bloc are former Muslim Brotherhood leader Abdel Moneim Abouel Fotouh and Hamdeen Sabbahi, a Nasserist. Other candidates are well respected among narrow circles but stand a slimmer chance of winning, such as leftist lawyer Khaled Ali and Judge Hesham al-Bastawisi.

Many initiatives to unite the revolutionary candidates have failed, but recently there have been calls for all the revolution supporters to vote for Abouel Fotouh as the strongest candidate in the group, regardless of their ideological beliefs, in order to avoid splitting the revolutionary votes.

In a column earlier this week, MP Mostafa El Naggar wrote that “strategic voting, the last resort” shows how the moment previously perceived as glorious and liberating has come down to calculations and damage control.

Alarmed by the rise of the candidates emerging from the old regime and the mobilization ability of the Brotherhood, Naggar tells supporters of the revolution that they no longer have the luxury to follow their hearts or be picky regarding ideology.

“Strategic voting means that the voter chooses the candidate they disagree with partially and doesn’t choose the one with a limited chance of winning whom they agree with completely, or else they would contribute to the winning of a third candidate that they completely disagree with,” he writes. “The interest of the nation now must rise above emotional choices and irrational alternatives.”

Mohamed El Dahshan, a writer, describes his experience voting from Tunisia a few days ahead of the vote in Egypt as bitter.

“Never would I have thought that casting a vote in our first presidential elections, more than a year after the revolution, would feel so uninspiring — bitter, even,” Dahshan wrote in a blog post.

Like many, Dahshan says he’s had to lower his expectations for the first post-revolution president to be able to choose from among the candidates.

Yasser al-Hawary, leading member in the Youth for Justice and Freedom movement regrets the absence of Nobel Laureate and former opposition activist Mohamed ElBaradei from the race. Hawary says that the former candidate who withdrew from the race in objection of the military council’s management of the transitional period could have been the one to unite the revolutionary forces.

“We were looking for the ideal president, now we are looking for the possible president,” says Hawary, who chose to vote for Abouel Fotouh.

With this rationale, Iman al-Tawil, a physician, has chosen Abouel Fotouh, considering the revolutionary candidate with the best chance to win.

“We are not convinced of anyone, but we are only voting because this was the first dream of the martyrs,” says Tawil, adding that if it wasn’t for the gratitude she feels for those who died during the revolution to give her this opportunity she would have boycotted the elections.

The presence of members of the old regime in the race, let alone their high chances of winning, saddens Tawil.

“Think of a martyr’s mother who’s still grieving over a son she lost in the revolution. How would she feel seeing a member of Mubarak’s regime as president?”

In the last few months, the most repeated demand in political demonstrations has been for the military rulers to hand over power to civilians. But as it turns out, the election of a president is not necessarily the happy ending.

“The presidential election is not the end of the transitional period, it’s the start,” says Rabab El Mahdy, a political science professor at the American University in Cairo.

Mahdy says that the new president will face a lot of resistance from those who have an interest against the full transition of power.

Mahdy is a leftist but supports Abouel Fotouh in the elections. For her, like many, the competition in the election is not one between ideologies but rather between revolutionary powers and the old regime.

Mahdy says that the winning of one of the candidates belonging to the old regime will be a loss for the revolution on more than one level.

“The election has a symbolic dimension; if one of the old regime candidates wins, it will be like giving legitimacy to this regime and it will be a symbolic loss for the revolution,” says El Mahdy.

This loss, she adds, will shake the people’s confidence in their revolutionary dreams and make it more difficult to continue the fight for their rights.