Authorities have recently released a number of political activists and prisoners of conscience in a bid to improve Egypt’s international image ahead of crucial parliamentary and presidential elections, analysts said.

Last week, Blogger Hany Nazeer was released after being detained without charge for 21 months on allegations of insulting Islam.

Nazeer’s release comes on the heels of recent promises by the government to release all prisoners arrested under Egypt’s emergency law for offenses unrelated to either drug trafficking or terrorism. In May, the 29-year-old emergency law was renewed for another two years, drawing ferocious criticism from rights groups and Egypt’s political opposition.

A blogger from the Upper Egyptian province of Qena, Nazeer was detained in October 2008 shortly after posting a link on his blog–Karez el-Hobb (“Evangelist of Love”)–to a controversial novel entitled Teiss Azazil fi Makka (“The Bull of Azazi in Mecca”). Said to have been written by a seventh century monk, the writer tells the tale of how he had inspired Prophet Mohammed to establish a new religion.

Nazeer’s blog had also contained posts about human rights and Coptic issues. “I talked about sectarian violence…and the Coptic situation and the difficulties associated with building churches and with Copts taking leading positions in government,” Nazeer said.

Nazeer’s link to the novel, however, ended up triggering angry reactions on the part of local Qena residents.

“After he posted the link to the novel, angry villagers besieged his house, so he ran away,” said lawyer Huda Nasrallah, who worked on the case.

According to Nasrallah, police took Nazeer’s brothers hostage in an effort to coerce the blogger into turning himself in to authorities.

“Hani surrendered when police threatened to take his sisters,” recalled Nasrallah. “He was then detained and transferred to Burg el-Arab prison.”

Nazeer was detained with the use of arrest warrants issued by the Ministry of Interior–a common practice under the emergency law. Although the court issued eight subsequent release orders, Nazeer remained behind bars.

“There were no official investigations of Nazeer within the last two years,” said Rawda Ahmed, a lawyer with the Arab Network for Human Rights Information who worked on the case. “And we were prevented three times from visiting him in prison despite having legal permission.”

Nazeer says his almost two years in detention were marked by considerable discomfort and occasional humiliations.

“Some 35 prisoners were confined to a 6.5-meter by 3.5-meter cell,” Nazeer told Al-Masry Al-Youm via telephone from Qena. “There were no beds, and we didn’t have enough room to sleep on our backs.”

“Once they punished all my cellmates by forcing them to undress in front of other prisoners,” Nazeer recalled. “Only myself and a couple others were exempted from the humiliation.”

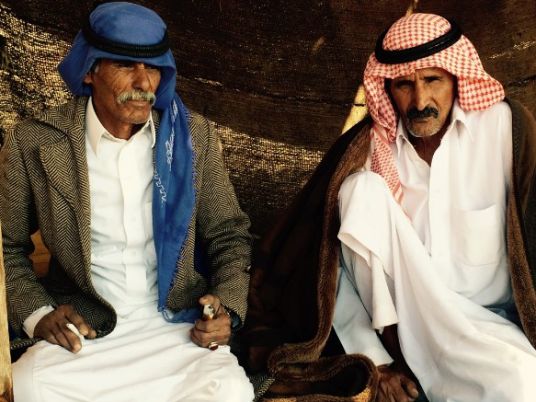

Throughout the course of Nazeer’s detention, a number of local and international human rights groups made appeals for his release. His case has made him one of Egypt’s most prominent prisoners of conscience, along with Bedouin activists Musaad Abu Fagr and Yahya Abu Maseera.

Analysts and human rights experts, however, believe the release of Nazeer, along with dozens of Bedouin activists, amounts to little more than an attempt on the part of the government to improve its image vis-a-vis human rights or to reduce tension with the Bedouin tribes of the Sinai Peninsula.

“The release of high-profile detainees is a message by the government to contain pressure on its human rights record, especially following the recent renewal of the emergency law,” said Hossam Bahgat, director of the Cairo-based Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

According to human rights organizations, around 300 detainees have been released since June, in line with the government’s earlier pledges.

Nevertheless, Bahgat dismissed the assumption that that the release of detainees is intended to improve the regime’s image domestically. “Releasing political detainees is still not a top priority on the opposition’s agenda,” he said.