Late on Tuesday night, the walls of the American University in Cairo (AUC) were no longer covered with the colorful murals of the martyred Al-Azhar Sheikh Emad Effat. The dead of the Port Said football violence, whose portraits had a few months ago replaced the faces of those who lost their eyes during the Mohamed Mahmoud Street clashes last November, vanished too.

Employees of the Cairo Governorate local council, with the protection of the police, removed the colorful graffiti painted on the AUC walls. Meters away, in Tahrir Square, construction workers are tirelessly working to renovate the middle of the square, covering dust with grass, and planting trees where just days ago there were tents and a makeshift gallows. The country’s revolutionary epicenter is changing again.

On Saturday, police dispersed demonstrators against the anti-Islam film, rampaging across Tahrir Square, burning tents, and evicting vendors. A sort of cleansing or re-ordering seems to have begun, and the erasure of the Mohamed Mahmoud street graffiti seems to be part of the plan.

It isn't just Tahrir which has seen crackdowns of late.

Police dispersed a sit-in by Public Transportation Authority workers demanding better wages, briefly detaining one of the strike leaders.

In addition, Nile University students protesting the public prosecutor’s decision to hand their campus over to Nobel Laureate Ahmed Zewail clashed with security forces who violently dispersed their sit-in, arresting five students who were released later.

In this context, some activists see the cleansing of the graffiti as a mark of an increasingly sanitized political environment, with little room for dissent or disruption.

Yet, others say that attempts to cleanse the square should not be taken so seriously. Before the Mohamed Mahmoud Street clashes in November there were similar attempts, rolled back by the rising tide of protest.

“The issue is not that harsh as many feel. It is a reflection of a traditional state mentality,” said Ammar Abo Bakr, a Luxor-based graffiti artist whose work filled the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street.

On Wednesday, Interior Ministry officials reportedly denied any responsibility for removing the murals.

Only the graffiti painted on the AUC walls at the beginning of Mohamed Mahmoud Street was removed; the rest of the artwork on the street is still vividly present.

Media reports previously said that the AUC administration vowed to protect the paintings on its walls, but AUC professor Kim Fox told Egypt Independent that it was only an initiative by some of the university’s faculty, and that the administration had not officially commented.

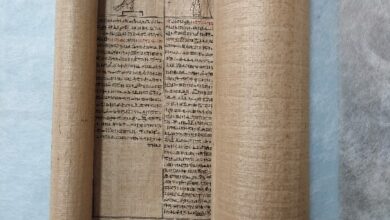

The attempt to remove the murals comes a few days before Al-Shorouk publishing house is expected to release a book entitled “The Walls are Chanting: The Graffiti of the Egyptian Revolution.”

“This is the retarded mentality of the regime,” Abo Bakr said. “They perceive graffiti as dirt that should be removed. This is what police officers were saying while they were covering the walls with white paint. They do not understand that this is art, not dirt. They will never understand.”

Security attempts on Tuesday to remove graffiti on Mohamed Mahmoud Street and the walls of the AUC buildings were not the first. Security forces have repeatedly painted over murals depicting those who were martyred and injured since the revolution erupted on 25 January.

Repeatedly in April and May, graffiti insulting members of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, was removed, then repainted. One face made up of two halves — ousted President Hosni Mubarak and SCAF head Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi — became iconic.

The latest removal attempts stirred the anger of activists who remember the Mohamed Mahmoud Street clashes, and saw their memories colorfully alive on the AUC walls.

Protesters and graffiti artists returned to the AUC walls on Wednesday afternoon to paint more graffiti and write anti-police slogans, in what transformed into a protest against police brutality and Muslim Brotherhood rule, as they projected their anger at the Brotherhood-affiliated President Mohammed Morsy.

Abo Bakr, along with other street artists, repainted the AUC wall with the face of a protester sticking his tongue out and saying, “Wipe it away again, you cowardly regime.”

Central Security Forces trucks were parked in front of the white walls, which were rapidly filled with anti-police slogans. Security officers standing nearby told Egypt Independent that their presence is to secure the street and the square, not to prevent protesters from painting graffiti.

The trucks withdrew shortly after when the number of protesters increased, as they cheered loudly to celebrate the police force’s departure.

More graffiti artists are planning to repaint the AUC walls on Friday, and the photos of the graffiti stencils published on Facebook seem to be more aggressive towards the Brotherhood and Morsy. Activists say that as the previous artwork was directed against Mubarak and the SCAF, now the graffiti shall be directed against the new regime that is following the steps of its predecessors in removing the revolutionary street art.

“This is what graffiti is all about. They remove the graffiti so we can paint it again, it is not that difficult. We are documenting history, and they cannot remove history,” Abo Bakr said.