As a means of popular expression, graffiti and street art have served to reflect the ongoing spirit of the 25 January revolution. At times, they have highlighted the demands of the revolution; at others, they have documented events and commemorated the many martyrs that have sacrificed their lives over the past 11 months.

The art first appeared on the walls surrounding Tahrir Square, and focused on stencils of deposed President Hosni Mubarak, with graffiti centered around messages like "Down with Mubarak," "Depart” and “Leave." Activists, artists, and protesters spray-painted such messages on the army's tanks and personnel carriers that were deployed in Tahrir Square and other city squares starting 29 January. The anti-police graffiti ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards), and "Police Are Thugs," were also spray-painted, particularly following violent confrontations with security forces in the early days of the revolution; similar graffiti has resurfaced with recent violence on Mohamed Mahmoud Street.

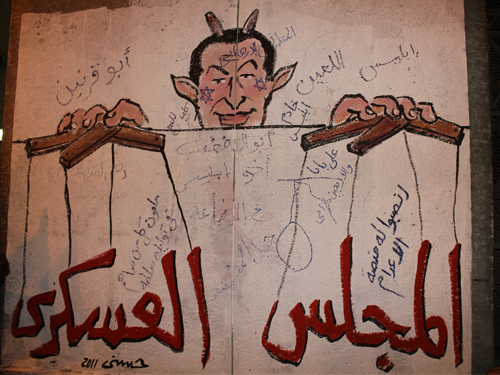

After the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) took over on 11 February, the themes of street artists began changing with the course of events. With Mubarak gone, graffiti began calling for the trial of the ousted dictator and his regime. When Mubarak and his sons finally appeared in court in August, calls for "a just trial" and "retribution" became the common themes.

Street artists were quick to react to the fact that while Mubarak, his sons, and top police officials have been put on trial before a civilian court, the ruling military junta has referred about 12,000 civilians to military tribunals since last winter's uprising. "No to military trials" and "No military trials for civilians" have been spray-painted across walls of downtown Cairo. And the iconic portrait of Amr al-Beheiri, a political activist who was arrested on 26 February and sentenced to five-years in prison by a military tribunal, was repainted several times. In fact, a group of street artists organized the “Mad Graffiti Weekend” in May in response to stencils of Beheiri and some of the revolution’s martyrs being painted over.

Following the authorities’ repeated crackdowns on protesters in Tahrir Square, Maspero, Mohamed Mahmoud Street and outside the cabinet, anti-SCAF graffiti immediately appeared on armored personnel carriers, as well as governmental and public buildings across the country.

In the second half of 2011, graffiti has returned to the "depart" theme — this time the message was directed at the SCAF. "Down with military rule" and "Down with the Field Marshal" appear to be the most widespread messages in Cairo and Aswan. Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi (and his iconic underwear), his deputy Sami Anan, and chief of military police Hamdy Badeen have been featured in numerous pieces of street art. "Wanted" stencils have been spray-painted for each of the leading generals.

The piece of street art that had the greatest impact this year was the “Wanted” stencil made for First Lieutenant Mahmoud Sobhi — dubbed the “eye-sniper.” Stencils of this junior police officer saturated Cairo's street walls after he was filmed firing birdshot into the eyes of protesters along Mohamed Mahmoud Street in November. The stencils called on people to search for Sobhi and hand him over for prosecution. Some included a LE5,000 reward. The “eye-sniper” handed himself in a few days after the manhunt began.

Over the past year, street art and graffiti have changed in both public and state perception from a form of “vandalism” to a valid form of protest, and although much has been erased in the past few months, more continues to crop up every day, a clear testament to the fact the “revolution continues.”