It resembled the welcome a warrior receives upon returning from victory.

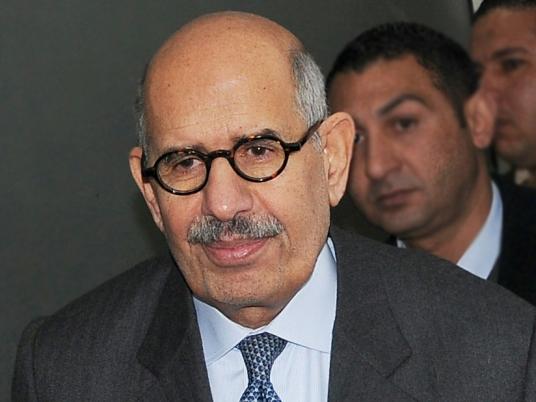

In February 2010, thousands of young Egyptians rallied at Cairo International Airport to receive the Nobel peace laureate Mohamed ElBaradei, not to congratulate him on a long career of esteemed international diplomacy but to express their vehement endorsement of a man whom they hoped would spearhead political reform in Egypt.

The festive scene encouraged the notion that new momentum for democratic change might take shape. Yet, after only a few months, the hype began to dissipate.

“There is a lot of disappointment especially among the most ardent supporters of ElBaradei,” says Manar al-Shorbagy, a political scientist at the American University in Cairo. “A lot of mistakes happened through last year that led to losing that momentum [for change].”

As the year nears its end, analysts are reflecting on the ElBaradei phenomenon, which stands as a 2010 landmark, to explain what went wrong and what could have or still can be done.

The former head of the UN nuclear watchdog first came to the fore as a reform advocate after throwing his full backing behind local opposition voices calling for a democratic transition. He went further by presenting himself as a potential alternative to the ruling regime. From abroad, he expressed his willingness to run for the presidency if a set of constitutional amendments were adopted to ease restrictions on presidential nominees. The announcement was followed by a wave of cyber activism in which thousands of Egyptians swore allegiance to the 68-year-old.

Upon his arrival to Egypt, several opposition figures rallied around him, helping to form the National Association for Change (NAC). Under his auspices, the NAC started collecting signatures in support of his seven reform demands which include lifting the state of emergency and introducing a package of constitutional amendments that would ensure full judicial oversight of elections and easier conditions to field presidential candidates. Since then, ElBaradei has been calling on Egyptians to sign his petition.

“If I have 10 million signatures on the petition, then I have a different platform," ElBaradei told Al-Masry Al-Youm earlier this month. "I won’t even need to speak to the regime because I’ll have a mandate.”

But for al-Shorbagy, Elbaradei’s framing of the reform debate around his seven demands is “a narrow way of looking at change”.

“When you tell people if you do not sign, then you are not part of change, you are imposing on them reform coming from above,” says al-Shorbagy. “If you are opening Egypt for change, this has to be from the bottom to the top. You need to make people decide.”

The media has been the primary tool of ElBaradei’s quest. He has promoted his cause fervently in both the foreign and local media. Dozens of interviews have been done with the new reformist in major Western newspapers, the most respected local privately-owned dailies, and TV stations.

In the lead-up to Egypt's recent parliamentary poll, ElBaradei consistently urged opposition parties to boycott, citing vote-rigging guarantees. Most parties turned a deaf ear to his call. Yet, as soon as the opening round concluded and proved to be fraudulent, the liberal Wafd party and the Muslim Brotherhood, the two most prominent opposition forces in Egypt, withdrew from the run-off.

Meanwhile, the government-owned press waged a smear campaign against him, accusing him of being ignorant of Egyptian realities. Some papers adopted a more vulgar approach by tapping into the man’s private life and questioning his faith in a highly religious and increasingly conservative Egyptian society.

“ElBaradei has to move from the media arena to the real organizational arena,” says Khalil al-Anani, Egyptian Political analyst at Durham University’s Insitute for Middle East Studies. “One of the possible scenarios is for him to join an existing party. If he has a problem with old traditional parties, he can join a new party like the [liberal] Democratic Front Party for example.”

Dina Shehata, an expert with Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, however, begs to differ.

“ElBaradei should be at an equal distance from all players,” says Shehata. “He is the symbol that should gather all national forces. He should not be counted as the ally of one particular party.”

Most Egyptian opposition parties suffer from internecine strife and lack any real grass-roots presence. Throughout his journey, ElBaradei has been reluctant to develop strong ties with such weak entities. He did, however, approach the Muslim Brotherhood, hoping the nation’s largest and most organized opposition group would endorse his plea. The group eventually posted his reform petition on its website calling on its members and sympathizers to sign. In only a few weeks, the site attracted hundreds of thousands of signatories. But such rapprochement between the liberal-minded politician and the Islamist faction of the opposition disappointed liberals, seculars and Copts alike, given the averse stance of ElBaradei’s new ally on democracy and secularism.

“Up until now, ElBaradei’s discourse has been fluid,” says al-Anani. “He should have his own project. He should clarify his position on the economy, the relationship between the state and religion and foreign policy. Up until now, we have not heard his views on the Palestinian issue for example.”

Al-Shorbagy agrees with al-Anani, contending ElBaradei still ignores issues that constitute major concerns to large segments of Egyptian society such as unemployment, poverty and relations with Israel.

“He does not discuss these issues; he considers them details,” she says. “If you avoid talking about issues that matter to the people, if you do not communicate with people through their own experience, then there is miscommunication.”

One of the main sources of many people’s disappointment in ElBaradei has also been his physical absence. ElBaradei spent most of 2010 abroad, only coming to Egypt on short visits. This attitude has to be changed if ElBaradei wants to bring about real change, contends Al-Ahram's Shehata.

“He has to take his role seriously and show some commitment," says Shehata. "Part-time activism does not work.”

ElBaradei came to the scene at a juncture where Egypt is torn by political and socio-economic disenchantment. Over the last six years, Mubarak has become the target of vehement local criticism. Voices calling on him to step down and embark on real democracy have grew in audacity.

Labor unrest have also put Mubarak’s regime under tremendous pressure. Thousands of social protests and strikes objecting to the regime’s neo-liberal economic policies have rocked Egypt over the last six years.

Besides, there is growing anxiety over the future of the presidency given that Mubarak has not said whether he will run for a sixth term in September 2011 presidential election.

“If it [ElBaradei’s phenomenon] continues on the same pattern, the momentum will be lost for good," concludes al-Shorbagy. "But not the momentum for change, the momentum for ElBaradei.”