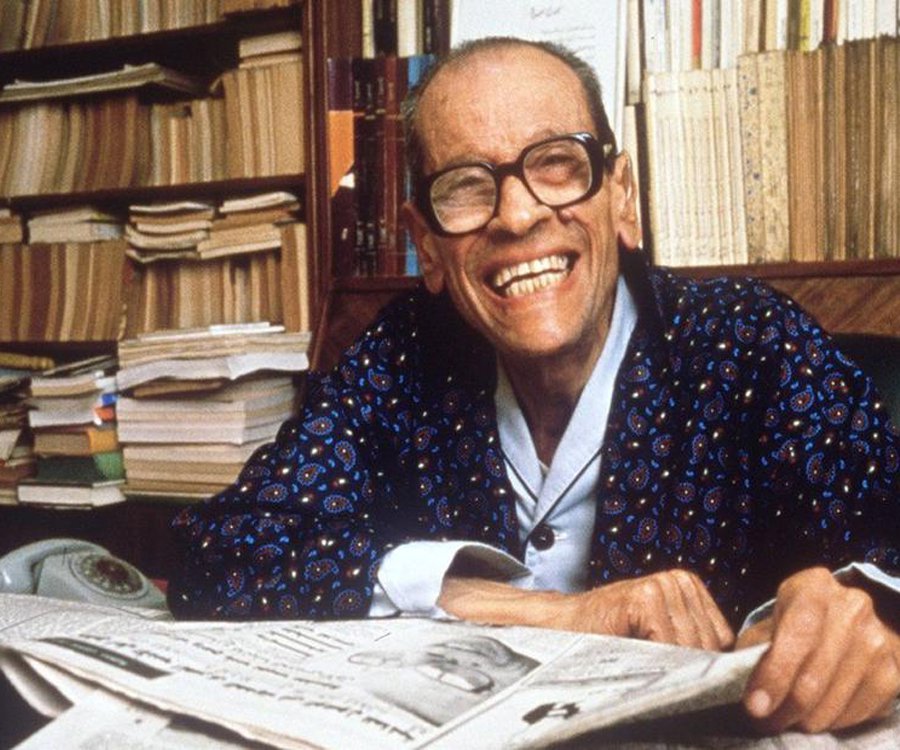

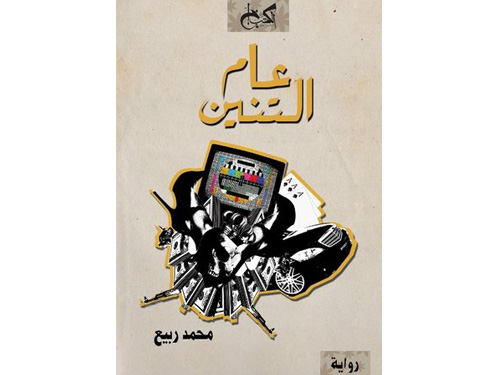

Egyptian novelist Mohamed Rabie comes off very shy compared to the daring topics he delves into in “The Year of the Dragon.” The 2012 novel explores life under the Mubarak regime using real and fictitious historical allusions that explain the nature of the bureaucracy and how it affects people’s lives.

“I didn’t intend to write a history,” Rabie tells Egypt Independent. “I was interested in seeing how the lives of some Egyptian characters are related to that of the head of the state.”

One of the novel’s characters, Naeem, who works in bookbinding, decides to die when he turns 60. His death isn’t physical though. Naeem prepares all the formal documents that make the government believe he’s dead so his family can claim a premium from an insurance company.

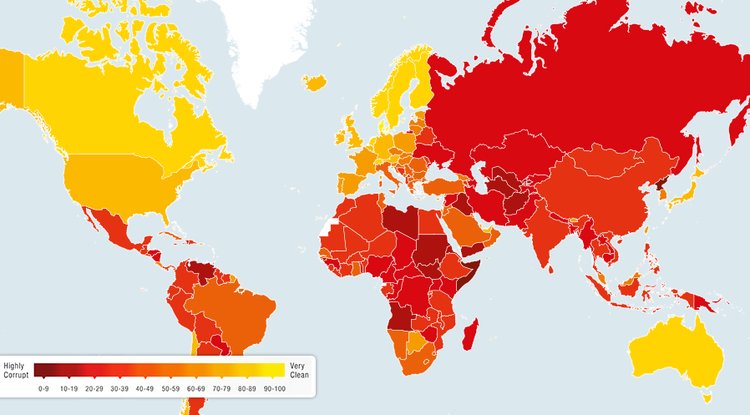

Another character in “The Year of the Dragon” is a man who repeatedly sends messages advising the president on how to deal with the people and maintain his rule; he proposes distracting them away from corruption by focusing on football games, TV programs, and sexual scandals of celebrities. The messages are sent to Salah, a public official close to Mubarak, in the hopes he will communicate them to the president.

In the novel, Mubarak is portrayed like a pharaoh, particularly in the raving scene in the end, in which Egyptians gather and enthrone him as king in 2012 — the year of the dragon according to the Chinese calendar. This imagery of the former president is weaved throughout the narrative as Rabie references events that reflect the nature of the regime.

“People describe my book as a political novel. But I don’t care for genres, it’s just a novel,” says Rabie. “I used two main ideas; the first was the stagnant life of Naeem, and the other one is expressed in the messages sent to Salah, which show that the seemingly stagnant political life in Egypt has a momentum underneath. We couldn’t observe it historically, but imagination allows me to surpass history [in my novel].”

Bureaucracy and the world of government officials are common themes in Rabie’s work. They were an essential element in his first novel “Kawkab Anbar” published in 2011 as Shaher, an employee at the Ministry of National Endowments, goes to write a report on a forgotten public library in Cairo that the state is considering demolishing because it’s in the way of the new metro line.

“You think that bureaucracy in Egypt is a strict system that exists to prevent gaps and frauds, but it doesn’t do that; what Naeem did could happen in reality,” Rabie says.

Rabie reflects on his experience with government officials that bring up this recurring theme in his writings, saying: “I’ve never worked for the government. But I have dealt with state officials. Bureaucracy makes you lose your morality; you are obliged to pay a bribe to get what you need.” He relates the stubbornness of minor state officials to their desire to be similar to the ruler.

In the novel, Naeem is aware of what employees want; he knows which documents can make him appear deceased. He knows how to bribe employees by giving them newspapers and magazines, if not money. Naeem doesn’t believe that he is committing fraud by claiming death; he is just “moving his name from one document to another.”

Cheating the government is nothing new, Rabie argues in his novel. He writes that in the early 19th century, when the state of Mohammed Ali Pasha decided to record all births in Egypt, prostitutes found themselves in trouble. They couldn't claim a father for their children. So a former clan chief named Abu Regl claimed the parentage for the children, and no one could prove that he was lying.

But Rabie’s boldness in “The Year of the Dragon” is not only in his poignant socio-political critique. He also experiments with language, using colloquial Egyptian words common on the streets rather than literature. “Ta’rees” for instance has no direct equivalent in English, but it is used to expresses hypocrisy and ignoring major faults as a widespread trait in Egypt over the past few years. The broken street language Naeem talks because of his aphasia condition is another example.

Rabie’s novels have been particularly popular among young readers. Asked what he thinks are the criteria of success for writers, he responds, “I don’t know, maybe the real success is to continue writing.”

In “The Year of the Dragon,” Rabie touches the political and banal daily experiences in people’s lives although the novel isn’t constrained by the limits of realism. He does, however, recognize the pressures currently placed on writers to be relevant.

“What is happening in Egypt seems horrible; the monotony that we used to live in gave us space to reflect on writing. That no longer exists,” he says. “Most people are interested in news, and I hope we [the writers] can surpass that soon.”