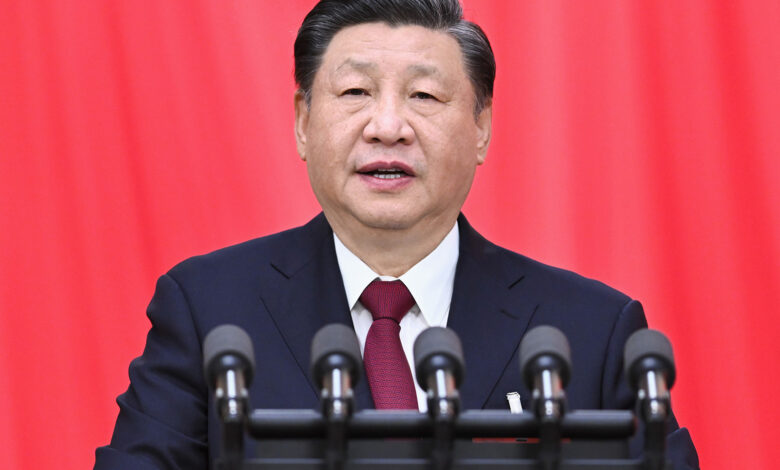

As is often the case with Beijing’s opaque decision-making, no explanation was given for Xi’s apparent decision to skip a major global gathering on which China has placed a high priority in the past. Premier Li Qiang, the country’s second-ranking leader, is expected to attend in Xi’s place.

Beijing’s reticence has invited a wide array of speculations and interpretations, from Xi’s potential health issues and domestic troubles at home to a snub at host country India, whose relations with China have frayed over an ongoing border dispute.

But viewed from the lens of China’s great power rivalry with the United States, analysts say Xi’s expected no-show at the G20 could also signal his disillusion with the existing global system of governance – and structures he sees as too dominated by American influence.

Instead, Xi may be prioritizing multilateral forums that fit into China’s own vision for how the world should be governed – such as the recently concluded BRICS summit and the upcoming Belt and Road Forum.

“There may be an element of a deliberate snub to India, but it could also be a statement that there are different governance structures Xi Jinping thinks are important – and the G20 may not be one of them,” said George Magnus, an economist and associate at the China Center at Oxford University.

“(Xi) may have wanted to make an example of the Indian G20 and said, ‘this is not something that I’m gonna go to because I’ve got bigger fish to fry.’”

Disillusion with G20

To some analysts, Xi’s absence may mark a shift in how China views the G20, a premier global forum that brings together the world’s leading advanced and emerging economies representing 80% of global GDP.

China used to see the platform as a relatively neutral space for global governance and placed a high priority on G20 diplomacy, said Jake Werner, a research fellow at the Quincy Institute in Washington DC.

Since its first leaders’ summit in 2008, China’s top leader has always attended the gathering – including by video link during the Covid pandemic. And when China hosted its first G20 summit in 2016, it pulled out all the stops to make the event a success and showcase its growing clout on the world stage.

Since then, however, relations between the world’s two largest economies have been fraught with rising tension and rivalry. Now, “China sees the G20 space as increasingly oriented toward the US and its agenda, which Xi Jinping regards as hostile to China,” Werner said.

About half of the group’s members are US allies, which the Biden administration has rallied to take a tougher stance in countering China. Beijing is also increasingly viewing tensions with other members – such as the border dispute with India – through its difficult relationship with the United States, Werner said.

Beijing has bristled at New Delhi’s growing ties with Washington, especially its engagement in the Quad – a US-led security grouping decried by Beijing as an “Indo-Pacific NATO.”

“China sees India in the anti-China camp and therefore doesn’t want to add value to a major international summit India is organising,” said Happymon Jacob, a professor of international studies at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Divisions over the Ukraine war are also casting a shadow over the summit. So far, India has not been able to broker a joint statement in any of the key G20 meetings since it took over the presidency last December.

China’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion and continued diplomatic support for Moscow has amplified its friction with the West.

“China has said that it thinks the G20 should be limited to economic discussions. It shouldn’t be politicized around the geopolitical fault lines that the United States and the Europeans want to push,” Werner said.

Chinese analysts concur that Beijing may see the G20 as a platform with diminishing value and effectiveness.

Shi Yinhong, an international relations professor at Renmin University, said the G20 has become a more “complicated and challenging” stage for Chinese diplomacy compared with several years ago, as the number of members friendly to China has dwindled.

Alternative governance structure

Xi last attended the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, in November last year, when he emerged from China’s Covid isolation and declared his return to the world stage. During the two-day summit, he held diplomatic meetings with 11 world leaders – including US President Joe Biden – and invited many of them to visit China.

Since then, a long line of foreign dignitaries have knocked on Beijing’s door to meet Xi, including G20 leaders from Germany, France, Brazil, Indonesia and the EU, as well as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

All the while, Xi has only made two trips abroad this year – and both are central to his attempt to reshape the global world order.

In March, Xi traveled to Moscow to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin – an “old friend” who shares his deep distrust in American power. Last month, he attended the BRICS summit of emerging nations in Johannesburg, South Africa, where the bloc announced the admission of six new members.

The expansion, hailed as “historic” by Xi, is a major victory for Beijing, which has long pushed to turn the loose economic grouping into a geopolitical counterweight to the West.

Magnus, the expert at Oxford University, said the expanded BRICS is an example of the alternative governance structure Beijing wants to build – it includes some of the most important countries in the Global South, with China taking a central role.

In recent years, Xi has laid out his vision for a new world order with the announcement of three global initiatives – the Global Security Initiative (a new security architecture without alliances), the Global Development Initiative (a new vehicle to fund economic growth) and the Global Civilization Initiative (a new state-defined values system that is not subject to bounds of universal values).

While broad and seemingly vague in substance, “they’re designed as an umbrella under which countries can coalesce around a narrative set by China, which is different from the kind of governance structure that prevails under G20 auspices,” Magnus said.

Next month, the Chinese leader is expected to host the Belt and Road Forum to mark the 10th anniversary of his global infrastructure and trade initiative – a key element in Beijing’s new global governance structure.

Magnus said initiatives like the Belt and Road, BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization – in which Beijing is either a founder or a major player – now have a much elevated status in China.

“These entities exist as alternative structures to the ones which China has traditionally joined and had to share the limelight with the United States,” he said.

“It’s also sending a message to the rest of the world – not just Global South countries but also wavering countries in the liberal democracy world – that this is China’s pitch.”