Monday marks the fifth annual World Autism Awareness Day, a day when autism organizations around the globe raise awareness through campaigns and fundraising events.

This year, the Egyptian Autistic Society has launched its first large-scale national awareness campaign under the slogans, “I’m autistic, give me a chance” and “I can’t speak much, but I have a lot to say,” in an attempt to attract attention to key issues surrounding the disorder in Egypt, where it still struggles to be officially recognized and addressed appropriately.

Autism is an inadequately understood neural disorder that appears in a child’s first three years of development, and can severely impair one’s social and communication skills for life, especially if left undiagnosed in its early stages.

Such impairments can make it difficult for people with autism to interact with and properly make sense of the world around them. Autism is considered a spectrum disorder, meaning that the condition affects different people in different ways.

Statistics from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention say that one in every 500 people has some form of autism, and despite continued awareness, recent updates from the center have shown this number to be rising.

Autism is also believed to have a genetic basis, and those with autistic relatives are 20 percent more prone to having the disorder. However, autistic people often do not exhibit clearly visible traits of the disorder, nor can it be clinically diagnosed through MRI and CT scans.

This fact has made it difficult to appropriately diagnose and address the condition in Egypt, where, for example, autistic people do not find themselves automatically exempt from military service duties and national educational requirements.

“People with disabilities are supposed to be exempt by default,” says Dalia Soliman, the founder of the Egyptian Autistic Society. “But with autism this is still not the case, as they refuse to put it on ID cards as a disability, so we have to constantly search for loopholes, such as having flatfoot, to be exempt from the army.”

But having an official label can be a double-edged sword, because particular high-functioning autistic persons — meaning that they’re only slightly impaired and may even excel in certain cognitive abilities — may miss out on potential job opportunities because they are marked as disabled on their ID cards.

“Autism needs a lot of attention, and it needs to be treated delicately and individually, which is no easy task, particularly here in Egypt,” says Soliman.

Currently, the Egyptian Autistic Society — licensed under the Social Affairs Ministry in 1999 — is the only nonprofit organization that specializes in fighting for the rights of and treating Egyptians with autism, sometimes even when patients lack the financial means. Other private institutions exist, but most are too expensive for the average Egyptian.

There are currently about 350 patients, aged 2 to 22, registered with the Egyptian Autistic Society.

Though it serves as a blessing for many families, the society’s nonprofit status and refusal to turn away patients has brought ongoing struggles, as the organization is continuously overloaded and suffers from a lack of funding and staff.

Funding is attained only by those patients whose families have the means to pay and through direct donations. Soliman says that “even when we find staff, all the training must be done internally.”

But despite the hardships, the organization continues to provide an indispensible service to the autistic community.

Concerned families can contact the Egyptian Autistic Society to receive a full diagnosis for relatives, followed by an individual education plan — because autism is a spectrum disorder — which can be provided at the organization’s headquarters in Maadi.

A key aspect of this plan, which is revolutionary in Egypt, is the idea of mainstreaming.

“Mainstreaming is really the essence of autism treatment: enabling those with autism to function independently within their respective communities,” says Soliman.

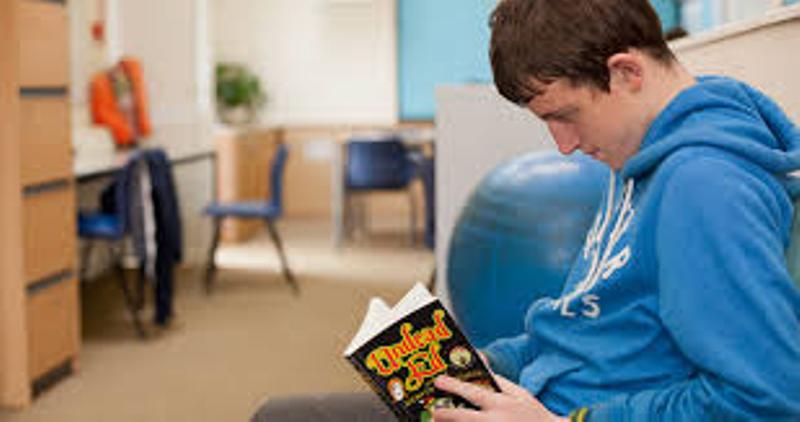

With this method, patients with autism attend regular schools with shadow guardians from the Egyptian Autistic Society so that they can develop their social and communication skills in the mainstream environment. A patient’s ability to mainstream, however, depends on their level of functionality.

With autism, the younger the individual is diagnosed, the higher chance there is that they might be able to function independently in society, says Soliman, who also adds that some of the first patients registered with the society in 1999, were around 10 years old at the time, and are still there.

However, Soliman says mainstreaming hasn’t always been an easy endeavor. In the organization’s early days, parents of students at many schools would threaten to make authorities shut down the school if the autistic child was not removed.

“People were afraid that the child with autism would infect the other students,” says Soliman. “Until recently, autism was still believed to be contagious, and probably still is by some.”

But years of raising awareness and fighting for the rights of those with autism have yielded results, as Soliman says that now most patients coming to the society are correctly diagnosed with autism, compared with 1999, when almost 70 percent were misdiagnosed as having some other disorder.

Also, full-time cooperation with another Maadi school, New Horizons, has also contributed to the success of the mainstreaming process.

Ranwa Yehia, whose 5-year-old son Nadim is now mainstreaming in his first year of school at New Horizons, says the program has really been a blessing, and that she feels lucky.

“Unfortunately, I am not the typical case,” says Yehia, whose youth development background and English-language speaking allowed her to quickly realize Nadim had autism at age 2. “If I only spoke Arabic, and had no background, I might not have realized.”

It is for reasons like this, and those aforementioned, that the first large-scale campaign on World Autism Awareness Day has been set up by the Egyptian Autistic Society.

Leading up to the awareness day, various YouTube autism awareness videos have also been circulating, repeating the slogans, “I’m autistic, give me a chance” and “I can’t speak much, but I have a lot to say.”

To celebrate the day itself, a symbolic walk from the Egyptian Autistic Society center in Maadi to the Wadi Degla protectorate will take place in the morning. Then, in the afternoon, a conference will be held at the center, where a 15-minute documentary on autism in Egypt will be released, followed by a celebratory carnival and live entertainment.

Finally, at night, the pyramids will be lit up in the color blue. Blue is the symbolic color associated with autism.

“While the campaign is a first, and quite exciting, what we really hope and need to see is a raised awareness and continued understanding and tolerance towards the issues in the long term,” says Sarah Nader, a coordinator at the society.

World Autism Awareness Day campaigning will continue to be promoted throughout the rest of the month of April, which is generally considered autism awareness month.