You may have heard that there’s a new Omicron spinoff that’s quickly gaining ground in the United States. Maybe you wanted to ask your doctor about it or search for more information online – but what was it called again?

Exactly.

Scientists know it as XBB.1.5, a name assigned because it is the second generation of the recombinant Omicron subvariant XBB.

X is the way scientists designate a recombinant, the result of two viruses that have swapped sections of their genetic material. The BB part is just alphabetical order. The first known recombinant was called XA, the second XB and so on. Now, they’ve run through the alphabet and are doubling up: XAA, XAB, all the way to XBB.

It hasn’t always been this hard.

In May 2021, the World Health Organization announced that in order to enable better public communication and to avoid the stigma of naming new variants after the countries where they were found, it would assign Greek letters to viruses that had acquired mutations that made them more transmissible, helped them evade current therapies, or made them more severe.

WHO said it would give these new names to viruses that its experts had designated as variants of interest or the even more consequential variants of concern. That gave us the familiar Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta variants as well as a slew of others that only rose to regional importance, like Epsilon, Theta and Mu.

It’s been more than a year since WHO gave a new variant a Greek letter name, however, creating a communications gap that some experts believe may be hindering efforts to protect public health.

Where did the Greek letters go?

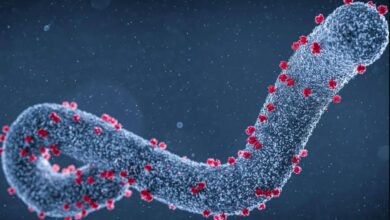

When Omicron – also known as BA.1 – blazed around the world starting in November 2021, it was so genetically distinct from the viruses that came before it that its branch of the SARS-CoV-2 family tree struck out in totally different direction.

Our immune systems barely recognized any of it. BA.1 generated new waves of infections, hospitalizations and deaths, as well as a slew of new descendants.

At the time, scientists argued that the second Omicron strain – BA.2, with dozens of new gene mutations –was as genetically distinct from BA.1 as Alpha, Gamma and Delta had been from each other. Some said they thought BA.2 deserved its own Greek letter.

But that never happened. Instead, WHO quietly stopped designating Variants of Concern or Variants of Interest categories that call for new Greek names.

Instead, it created a new category, Omicron Subvariants under Monitoring, to signal to public health officials which of these spinoffs should be watched – which might sound a lot like the reason to designate variants of interest and variants of concern in the first place.

The organization left the door open to designate new names if it deems a variant to be sufficiently different, but it hasn’t seen the need to do that for more than a year.

Yet the coronavirus has continued to evolve, becoming more transmissible and more immune-evasive over time. These changes have been consequential, too.

As Omicron has mutated, for example, immunocompromised patients have lost key therapies like the long-acting antibodies in the preventive Evusheld. All of the monoclonal antibodies developed to help people with severe Covid-19 infections have lost their punch against the latest subvariants.

The mRNA vaccines have also been updated in an effort to better protect people from the currently circulating viruses that cause Covid-19.

Still, WHO says it doesn’t see a need to distinguish between them.

“The fact that the many individual (sub)variants are not given their own label does not diminish the importance of these variants,” WHO spokesperson Christian Lindmeier said in an emailed statement.

“A new label, (i.e. a new assignment of a variant of concern,) would be given if there is a variant sufficiently different in its public health impact, and which would require a change in the public health response,” Lindmeier wrote.

A false sense of security

Some scientists say they agree with this strategy.

“I am actually fine with not giving new Greek letters to subvariants of Omicron,” Michael Worobey, a computational biologist who studies pandemics through viral genomics and viral evolution at the University of Arizona, wrote in an email to CNN.

Worobey points out that there are two ways the new coronavirus has been changing over time. The first is by moving, continuing to circulate and infect people around the world. This type of evolution happens more incrementally and generally doesn’t cause many big changes at once.

The second way viruses change is by camping out, chronically infecting people with impaired immune function. One person in Houston has been tested as recently as October and found to be infected with a version of the Delta variant that has acquired 17 mutations in its genome, Worobey said. There’s another patient in Spain with almost as many mutations.

Worobey says these viruses have the potential to create another Omicron-level emergence, and he’s OK not naming Pi until one of these zombie viruses emerges and begins to spread.

But others think WHO’s shift in strategy could be misleading.

“Variants within Omicron are really pronounced and distinctive. It’s not like Omicron is one thing at all. It has evolved hugely,” said Bette Korber, a laboratory fellow and variant specialist at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Korber says that even when Omicron emerged, it had two “parents,” BA.1 and BA.2.

And each has continued to evolve, so scientists have logged more than 650 subvariants and sublineages within the Omicron strain.

“But the WHO has stopped naming them at this point, so [people] get a false sense of security,” Korber said. Continuing to use the Omicron name makes it sound like the virus isn’t changing anymore, “but in fact, it’s changing hugely.”

Korber said she’s been in public lectures where “very good doctors” have said, ” ‘Well, now it’s not evolving anymore. It’s just been Omicron for over a year, so you don’t have to worry about that anymore.’ ”

Looking for better ways to communicate

Ryan Gregory, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada, says that without new Greek letter names, we’ve lost the ability to easily communicate about the virus.

“If you said ‘what’s that rustling around in the bush?’ and someone else said ‘a mammal,’ well, that’s not especially helpful, right? It’s not enough information.”

Scientific names for sublineages like BQ.1.1 are very precise, he says, but they quickly get unwieldy. It’s like calling the mammal in the bushes by its Latin name, Mus musculus.

“What we are missing is the equivalent of, in animal and plant taxonomy, the common name. So if you said ‘what is that’ and I said ‘it’s either a mouse or a rat,’ now you know exactly what I’m talking about,” he said.

It’s so frustrating for even scientists to discuss subvariants that Gregory decided to make up his own nickname for XBB.1.5: Kraken, after the mythological sea monster. It has stuck so far.

He isn’t the first to take on the task. Before Kraken, social media users dubbed the BA.2.75 subvariant Centarus. It was also a hit.

Gregory says the names caught on because they serve a purpose, allowing people to have thoughtful discussions about the virus, its changes and how it could affect them.

But DIY naming isn’t a perfect solution, as it isn’t exactly standardized. Mention Kraken to someone who isn’t on Twitter, and they might not know what you’re talking about.

“My strong preference really would be that we don’t need names because we’ve not seen the constant evolution of many more variants that we need to watch. That will be the best because we’ve mitigated them,” Gregory said.

But a close second would be a formal naming system handled by appropriate groups that would be used specifically for communication so people can be kept up to date, he said. “Not to cause panic, obviously, but to let people be informed and not get lost amongst the obviously technical stuff.”