“I am torn between two fathers. Both are from the same generation, both have roots in Upper Egypt, and both are the embodiment of fatherhood. One is a shared public father for everyone, and the other is a personal father. My public father is a leader who is often spoken of in the home, street and school. He is everywhere like nature. Like the water, air, soil or rays of the sun. My personal private dad is different. In a moment, I can run into his bedroom.”

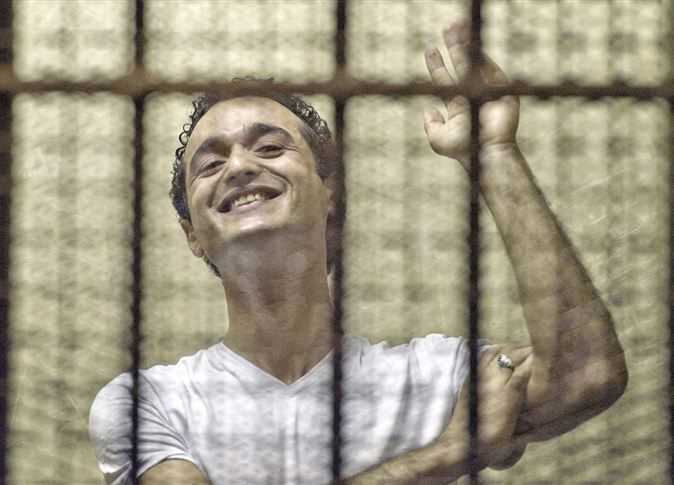

Nine-year-old Nada Abdelkader narrates a reality for generations of Egyptians. She is the embattled protagonist in Radwa Ashour’s 2008 novel Farag whose Sorbonne-educated father was imprisoned by her “public father” Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1959 for espousing “questionable” views. Confused by the absence of her biological father and the pervasiveness of the nation’s caregiver, Nada explains that despite pride in her father “it was Nasser who raised me.” Later in life, Nada would herself join a line of family members who were imprisoned for their political dissidence at the hands of Egypt’s successive totalitarian “fathers”.

For millennia, Egypt’s “fathers” have been omnipresent. They adorned every public space in the country. From sphinxes in their likeness and obelisks describing their insurmountable achievements, to every government office and street corner decorated with varnished, to doctored photos of their younger selves. Since his assumption to the presidency, Hosni Mubarak has tried to craft a different kind of image for himself compared to his predecessors. In contrast to Nasser’s image as the consummate populist leader and Sadat’s wiser-than-thou wily visionary depiction, Mubarak adopted the image of a benevolent, tolerant, and compassionate father. Of the three, his was the only officially commissioned photograph where the president smiled as if comfortingly saying, “with me, everything is alright.” While his characteristic smile led some to dub him “la vache qui ri” (the laughing cow), it deceptively fore-grounded Egypt’s slow and crippling deterioration. This was a father whose inability to judge the severity of his country’s ailments was beyond even the parody of leadership in Albert Kossary’s The Joker.

Fathers are meant to provide. In his 30-year paternal tenure, Mubarak transformed a caregiver state into one that punished its people. He spoke of bounty but provided none of it. He expressed egalitarianism but acted preferentially. He advocated for the masses but empowered the few. And he did it all while smiling at Egyptians everywhere they looked. For most, he was a wolf in sheep's clothing, a father whose kind exterior underplayed his ruthless core. And to some, Mubarak was the blemish-free and kind father without whose watchful eye we could not function or survive. Those were the blindly obedient who advocated for so-called stability and security throughout the 18 days of protest, whom Egyptians have mockingly called the “Couch Party”.

After Mubarak’s seemingly permanent move to Sharm El-Sheikh post-February 11, the “Couch Party” has developed new approaches to old agendas — celebrate the revolution, appropriate its symbols and accomplishments, demand an end to demands, and attack the protesters, figuratively and literally. Today members of the “Couch Party” have descended onto the streets in their slim hundreds, labeling themselves the “silent majority” to disempower the unfinished revolution. Buoyed by a court decision to overturn a ruling to remove the name and image of Mubarak and family from public establishments, they converged on Roxy Square to apologize and honor him and plead for continued military rule. With the encouragement of Supreme Council for the Armed Forces' (SCAF) smear campaign to demonize the April 6 youth movement, the silent majority turned into a violent minority, attacking peaceful protesters marching towards the Ministry of Defense headquarters. All the while, Egypt’s new foster father, SCAF, has condoned “public” actions against critics with central security and military police providing cover.

The latest episode involves a smear campaign by SCAF member General Hassan El-Roweiny who accused the April 6 youth movement of receiving foreign assistance in the form of training in peaceful protest at the hands of Serbian student movement Otpor! The irony of this claim is deplorable and laughable in equal measure. It should be no secret to anyone that the military is the country’s largest single recipient of foreign assistance, with $1.3 billion annually from the US government alone. Clearly, they are turning to the age-old fathers’ mantra, “do as I say, not as I do.”

But the military’s camouflage uniforms have started to wear off. For a revolution that takes pride in its leaderlessness, the army's only option has been to try and remain outside the limelight, concealing their role as the political puppeteers in the hardly post-Mubarak era. Yet there is no mistake; SCAF is calling all the shots behind closed doors, engineering their invisible yet eternal presence while carefully deflecting attention and scrutiny. Signs of this are now aplenty, but it is hardly more evident than in an incident relayed by Hossam Bahgat of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) who attended a British Embassy reception with 150 other invitees on 9 June to commemorate the Queen’s birthday. The newly appointed UK Ambassador James Watt dutifully stood up and raised a toast in honor of Field Marshall Tantawi, referring to him as “Egypt’s acting president.” Evidently, in the hallways of power, there is no people’s revolution. What does this mean? Could this revolution be a remarkable and historic sleight of hand? Has SCAF packaged and delivered a soft coup d’etat in a civilian revolution’s gift wrapping?

In this ongoing struggle between competing powers — street vs. state apparatus — Egypt’s authorities may have miscalculated and underestimated the revolutionaries’ threshold for infantilization. This is not the same country where the child Nada Abdelkader revered her "public father" Nasser. Instead, she has now come of age, dissented, and disowned all forms of patriarchy. Egypt’s interim rulers must realize their rule is mandatorily interim. The new Egypt no longer bows to paternalism, but rather rejoices in its orphanhood.

Adel Iskandar is a media scholar and lecturer at Georgetown University.