The attacks have forced some of the world’s biggest shipping and oil companies to suspend transit through one of the world’s most important maritime trade routes, which could potentially cause a shock to the global economy.

The Huthis are believed to have been armed and trained by Iran, and there are fears that their attacks could escalate Israel’s war against Hamas into a wider regional conflict.

Here’s what we know about the Huthis and why they are getting involved in the war.

Who are the Huthis?

The Huthi movement, also known as Ansarallah (Supporters of God), is one side of the Yemeni civil war that has raged for nearly a decade. It emerged in the 1990s, when its leader, Hussein al-Huthi, launched “Believing Youth,” a religious revival movement for a centuries-old subsect of Shia Islam called Zaidism.

The Zaidis ruled Yemen for centuries but were marginalized under the Sunni regime that came to power after the 1962 civil war. Al-Huthi’s movement was founded to represent Zaidis and resist radical Sunnism, particularly Wahhabi ideas from Saudi Arabia. His closest followers became known as Huthis.

How did they gain power?

Ali Abdullah Saleh, the first president of Yemen after the 1990 unification of North and South Yemen, initially supported the Believing Youth. But as the movement’s popularity grew and anti-government rhetoric sharpened, it became a threat to Saleh. Things came to a head in 2003, when Saleh supported the United States invasion of Iraq, which many Yemenis opposed.

For al-Huthi, the rift was an opportunity. Seizing on the public outrage, he organized mass demonstrations. After months of disorder, Saleh issued a warrant for his arrest.

Al-Huthi was killed in September 2004 by Yemeni forces, but his movement lived on. The Huthi military wing grew as more fighters joined the cause. Emboldened by the early Arab Spring protests in 2011, they took control of the northern province of Saada and called for the end of the Saleh regime.

Do the Huthis control Yemen?

Saleh agreed in 2011 to hand power to his Vice President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, but this government was no more popular. The Huthis struck again in 2014, taking control of parts of Sanaa, Yemen’s capital, before eventually storming the presidential palace early the next year.

Hadi fled to Saudi Arabia, which launched a war against the Huthis at his request in March 2015. What was expected to be a swift campaign lasted years: A ceasefire was finally signed in 2022. It lapsed after six months but the warring parties haven’t returned to full-scale conflict.

The United Nations has said that the war in Yemen has turned into the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Nearly a quarter of a million people have been killed during the conflict, according to UN statistics.

Since the ceasefire, the Huthis have consolidated their control over most of northern Yemen. They have also sought a deal with the Saudis that would bring the war to a permanent end and cement their role as the country’s rulers.

Who are their allies?

The Huthis are backed by Iran, which began increasing its aid to the group in 2014 as the civil war escalated and as its rivalry with Saudi Arabia intensified. Iran has provided the group with weapons and technology for, among other things, sea mines, ballistic and cruise missiles, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones), according to a 2021 report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The Huthis form part of Iran’s so-called “Axis of Resistance” – an Iran-led anti-Israel and anti-Western alliance of regional militias backed by the Islamic Republic. Along with Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Huthis are one of three prominent Iran-backed militias that have launched attacks on Israel in recent weeks.

How powerful are the Huthis?

American officials have been tracking iterative improvements in the range, accuracy and lethality of the Huthis’ domestically produced missiles. Initially, home-grown Huthi weapons were largely assembled with Iranian components smuggled into Yemen in pieces, an official familiar with US intelligence told CNN previously.

But they have made progressive modifications that have added up to big overall improvements, the official said. In a novel development, the Huthis have used medium-range ballistic missiles against Israel, firing a salvo of projectiles at Israel’s southern region of Eilat in early December, which Israel said it intercepted.

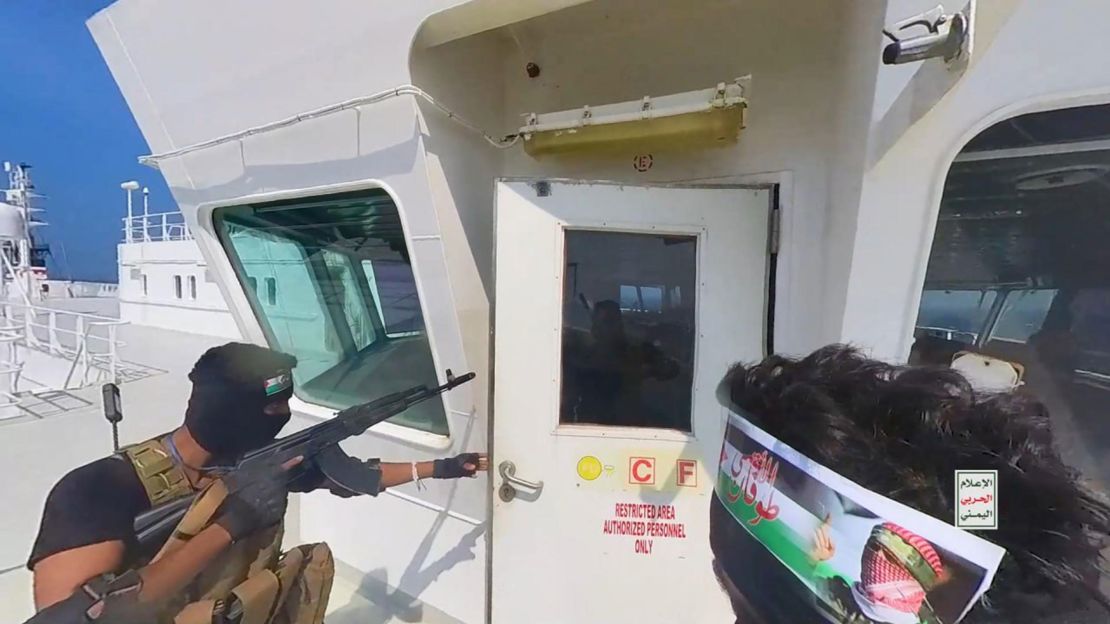

While the Huthis may not be able to pose a serious threat to Israel, their technology can wreak havoc in the Red Sea. They have used drones and anti-ship missiles to target commercial ships – some of which aren’t believed to be linked to Israel – prompting the USS Carney, a warship in the Red Sea, to respond to distress calls.

Why are the Huthis attacking ships in the Red Sea?

While, through a combination of geography and technology, the Huthis may lack the capabilities of Hamas and Hezbollah, their strikes on commercial vessels in the Red Sea may inflict a different sort of pain on Israel and its allies.

The global economy has been served a series of painful reminders of the importance of this narrow stretch of sea, which runs from the Bab-el-Mandeb straits off the coast of Yemen to the Suez Canal in northern Egypt – and through which 12 percent of global trade flows, including 30 percent of global container traffic.

In 2021, a ship called the Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal, blocking the vital trade artery for nearly a week – holding up as much as $10 billion in cargo each day – and causing disruptions to global supply chains that lasted far longer.

There are fears that the Huthi drone and missile attacks against commercial vessels, which have occurred almost daily since December 9, could cause an even greater shock to the world economy.

Four of the world’s five major shipping firms – Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, CMA CGM Group and Evergreen – have announced they would pause shipping through the Red Sea amid fears of Huthi attacks. The oil giant BP said on Monday it would do the same – a move that caused oil and gas prices to surge.

The attacks could force ships to take a far longer route around Africa and cause insurance costs to rocket. Companies could pass on the increased cost of moving their goods to consumers, raising prices again at a time when governments around the world have struggled to tame post-pandemic inflation.

The Huthis say they will only relent when Israel allows the entry of food and medicine into Gaza; its strikes could be intended to inflict economic pain on Israel’s allies in the hope they will pressure it to cease its bombardment of the enclave.

Championing the Palestinian cause could also be an attempt to gain legitimacy at home and in the region as they seek to control northern Yemen. It could also give them an upper hand against their Arab adversaries, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who they accuse of being lackeys of the US and Israel.

How has the world reacted?

The attacks could be intended to drag more countries into the conflict. Israel has warned that it is ready to act against the Huthis if the international community does not. National Security Adviser Tzachi Hanegbi said this month that there needs to be a “global arrangement” to address the threat “because it is a global issue,” referring to the Huthi attacks as a “naval siege.”

The US on Monday announced a new multinational naval task force comprising the United Kingdom, Bahrain, Canada, France, Norway and others, to “tackle the challenge posed by this non-state actor” that “threatens the free flow of commerce, endangers innocent mariners, and violates international law.”

Mohammed al-Bukhaiti, a Huthi spokesperson, told Al Jazeera on Monday that the group would confront any US-led coalition in the Red Sea.

Just as the Biden administration is beginning to yield to pressure for it to push Israel to wind down its campaign in Gaza, the US may find itself being pulled more deeply into the Middle East by the ragtag – but effective – Huthi rebels who have made themselves impossible to ignore.

CNN’s Katie Bo Lillis and Natasha Bertrand contributed reporting.