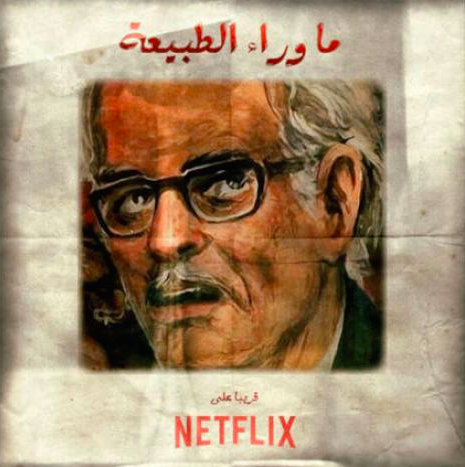

When Egyptian author Ahmed Khaled Tawfik first launched his hit horror book series “Ma Waraa al-Tabee’a” (Beyond The Natural World) in 1993, he found nothing better to begin with than the character of Dracula. In the series’ debut story “The Vampire,” a group of scientists try to bring Count Dracula back to life.

A hundred years after Bram Stoker’s death – 2012 marks the Irish writer’s centenary – his best-known novel “Dracula” remains the ultimate symbol of horror in various cultures.

“Bram Stoker’s story continues to have a huge impact on people,” says Tawfik, “as all cultures have this fear of vampires.” Tawfik adds that anyone interested in horror literature must have read “Dracula” at least once, although in Arab countries, this mostly happens in other languages.

Despite the popularity of the novel, it remains quite difficult to find a complete Arabic translation of “Dracula.” Tawfik says he once read a complete one, which he found in his father’s library, but could not remember the name of the translator.

Among the available abridged versions of “Dracula” is a 2011 translation by Bashar Rafee that was published by the Syrian Rislan Publishing House. Another was published by the Egyptian Dar al-Hilal in 2005. In the latter, translator Lucy Yacoub summarized what she dropped out in a couple of words to keep the story flowing. Dar al-Bihar, famous for publishing short versions of classics, also released in the same year a bilingual (English-Arabic) version of Dracula.

But Tawfik considers himself the first to introduce the character of Dracula to Arabic readers, particularly young ones among which his books are very popular. He featured it in “The Vampire,” and a two-part narrative: “The Myth of Pale Ones” and “The Myth of Blood of Dracula.” In them, he writes about a Romanian village plagued by vampires and waiting for Dracula’s return.

Like literature, “Dracula” is also present in Arab cinema and theater, although he is often presented in a comedic context, as a parody for villains and corrupt individuals. Kuwaiti playwright and theater director Abdel Aziz al-Mossalam, for instance, who experimented with horror theater, produced a number of plays in the late nineties like “The Vampire” and “Dracula Time.” “Dracula Time” was about a vampire who sucks the blood of the newly married Badreya and turns her into a vampire; so her family seeks out Dracula to save her. The production was big, yet it was awkwardly complemented with many songs, dances and jokes.

Egyptian theater has also experimented with “Dracula.” In 1989, theater director Abdel Ghany Zaki presented a commercial adaptation by Magdy al-Ebiary titled “Dracula’s Sons.” Ebiary used the idea of sucking people’s blood as a metaphor for drug trade.

As for Egyptian cinema, the most prominent experiment with “Dracula” was the 1981 film “Fangs.” Written for the screen and directed by the late Mohamed Shebl who was fond of horror films, “Fangs” is a horror-as-social-commentary kind of production. Popular Shaabi singer Ahmed Adaweya starred as Dracula, the prince of darkness. In the experimental film, Dracula imprisons a young man and his fiancée in his palace, like Stoker’s Dracula who imprisoned Jonathan Harker, and he wants to suck the girl’s blood and turn her into a vampire. But the film’s narrator, the late filmmaker Hassan al-Imam, clearly says the moral of the story: sucking blood is not exclusive to myths, making reference to the social and political corruption of the seventies. The film ends with the revolutionary act of rebellion where the people let the burning sunlight into Dracula’s palace.

But, Dracula or “The Undead” as Stocker initially titled his novel, does not die, and continues to inspire various works of art across cultures.