Every few minutes the ground shakes as blasts echo through the battered streets of Siversk, in eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk region. Sometimes it’s outgoing Ukrainian fire, sometimes the Russians firing back.

An elderly woman in black pants, heavy shoes, and a dirty grey overcoat and headscarf shuffles up the street. Another explosion rings out. She flinches, her eyes open wide, but she doesn’t miss a step. She joins a crowd of several dozen, mostly elderly residents bundled up against the cold.

The roads are covered with mud and rubble thrown up by countless incoming rounds. The few vehicles must swerve around water-filled craters where bombs fell. The upper floors of some apartment blocks have been reduced to rubble and barely a window on the street is intact. Telephone and electrical wires snake along the ground, long dead.

On the edge of the crowd, standing alone, is 72-year-old Lubov Bilenko. Her face is flat, devoid of emotion, her dark eyes without expression – the thousand-mile stare.

“Of course, we were very scared before,” she says in a low voice. “Now we’re used to it,” she says of the shelling. “We don’t even pay attention anymore.”

Bilenko tells CNN she has ventured out of her apartment, where she lives alone, to the main road to collect her monthly pension, brought to town by a mobile unit of Ukrposhta, the Ukrainian Postal Service. Bilenko’s pension is just short of $80 a month. It’s just enough to buy a bit of food from one of the few shops still open.

The little yellow-and-white Ukrposhta van comes to Siversk once a month.

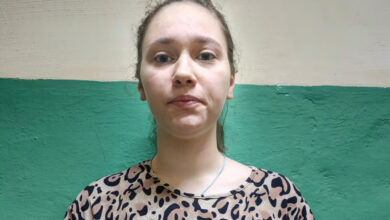

Anna Fesenko, a blonde woman with a quick smile, heads the mobile unit. As she and her colleagues check documents against a list of recipients and hand out cash, Anna coaxes a smile and an occasional chuckle from weary town residents.

Fesenko says she has been with Ukrposhta for 15 years. Those years of predictable, methodical postal work didn’t prepare her for what she does now.

“I could never have imagined such a nightmare,” she tells CNN.

Before heading the mobile unit, Fesenko worked at the post office in Bakhmut, about 22 miles south of Siversk. But in mid-fall the fighting around the town became so intense that she and her colleagues there had to evacuate.

She understands her job is not just to hand out pensions: It’s to remind the people in Siversk they haven’t been forgotten. “I think we’re the only one connection between them and the rest of the world,” she says.

Not everyone, however, is willing to even go outside.

“I live within a 20-minute walk from here, but my wife is afraid to come here,” says 63-year-old Volodymyr, who declined to give his full name, pulling on a cigarette before joining the line.

“My wife told me not to spend our pension on cigarettes,” he chuckles, taking another deep drag.

Olha, 73, has made it to the front. Like so many living in the war zone, she has spent months huddling with others in the basement of her apartment building. It’s a cramped, uncomfortable existence. Yet she is willing to put up with it.

“I was born here,” she says, nodding her head forward for emphasis. “This is my motherland.”

Then, yet another loud blast. Olha barely notices. “I will not go anywhere. What will be, will be.”

Overseeing the operation is the head of the Siversk military administration, Oleksi Vorobiov. He’s nervous that so many people have gathered out in the open.

Russian forces are just across a wide valley, occupying hills visible from the pension distribution point. They’re about 10 kilometers (six miles) to the north.

Vorobiov urges people to move back, to spread out “for your own safety.” They ignore him.

“We are trying to choose the right time and place,” Vorobiov says of the pension handout. That means every time the mobile unit comes, it’s a different place and time to avoid being targeted by the Russians.

“But this is war,” he adds. “Today it’s like this” – he nods to the crowd waiting in line – “and tomorrow it can be totally different.”

We left Siversk around noon. The distribution was only halfway done.

An hour later a Russian artillery round slammed into the ground just a block away, Fesenko, the postal official, told us by phone.

No one was injured, she said, but she and her colleagues dispensed with formalities. They quickly handed out the cash they could to those still waiting, she said, and left.