Yemen: Dancing on the Heads of Snakes by Victoria Clark (Yale, 2010)

Largely ignored, Yemen was prominent for a brief time in world headlines when it was said to have been the country of origin for the explosives that a young Nigerian man used in an attempt to blow up an airplane outside of Detroit, Michigan. This was last December, and interest in this important and fascinating country eventually waned. But a new book by Yemeni-born journalist Victoria Clark will hopefully redirect some needed attention to the country.

Yemen: Dancing on the Heads of Snakes (the subtitle references Ali Abdullah Saleh’s own metaphor for ruling the country) is “a lively mix of politics, travelogue and history.” Its potential for furthering discussion on Yemen, before that discussion is forgotten entirely, is deemed impressive: “For the armchair commentators at Fox News and similar organizations, this book ought to be required reading. It is easily the best and most readable account of Yemen’s current problems and their daunting complexity.”

The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898 by Evan Thomas (Little, Brown & Company, 2010) and The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War by James Bradley (Little, Brown & Company, 2009)

Now that America is at war with two countries and its president has nevertheless been given the Nobel Peace Prize, one might hear the echoes of a different president: Theodore Roosevelt, who also won the award for peace in spite of his not unappreciative attitude toward war. Two new histories by Evan Thomas, editor at large at Newsweek, and James Bradley, author of Flags of our Fathers, don’t focus exclusively on Roosevelt, but in their books about America and war, Roosevelt nevertheless “hovers over and inside them.”

Thomas’s book, which focuses on Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and William Randolph Hearst–in addition to Roosevelt–“with its style and panache, is hard to forget and hard to put down.” Bradley has written a “provocative study of a little-remembered ‘imperial cruise’ that, in [Bradley’s] view, set the stage for World War II in the Pacific.”

War Games: The Story of Aid and War in Modern Times by Linda Pollman (Viking, 2010)

“Does humanitarian aid prolong wars?” is the provocatively titled review of Dutch writer Linda Pollman’s likewise provocatively titled book, War Games, in which she asserts that “humanitarianism has become a massive industry that, along with the global media, forms an unholy alliance with warmongers.” It’s an undoubtedly polarizing argument, but a necessary one, for as it becomes increasingly difficult to target those in need, there is a greater chance that aid will go to the perpetrators.

Pollman’s book is passionately written and researched, but her “indignation is large enough to contain a variety of contradictions.” Nevertheless, War Games is as convincing as it is disconcerting.

Into Suez by Stevie Davies (Parthian, October 2010)

The idea for Stevie Davies’–who the reviewer refers to as “one of our most consistent and continually undervalued writers”–11th novel, Into Suez, came while the author was protesting the Iraq War, because “Suez could be seen as the blueprint for every instance of disastrously mishandled Middle Eastern policy that followed.” Through her protagonist, Alisa, who, along with her daughter, joins her husband who is serving at Ismailia, Davies manages to “encapsulate imperial wrong-headedness in a single, indelibly recorded incident.”

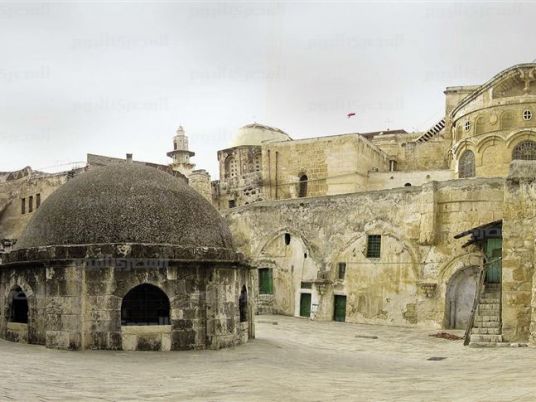

A Wall in Palestine by René Backmann, Translated from the French by A. Kaiser (Picador, February 2010) and Rebel Land: Unraveling the Riddle of History in a Turkish Town by Christopher de Bellaigue (Penguin Press, March 2010)

These two new books examine the importance of language in conflict and post-conflict societies. An insightful review in the Los Angeles times calls Rene Backman’s thorough discussion of the wall in Palestine “worthwhile reading even for those who don’t agree with its conclusions.” Christopher de Balligue, meanwhile, is described as “a lovely writer, thorough reporter and deep thinker, although his mix of historical figures and local characters is sometimes hard to follow.”