Though it was a couple of years ago, weathercaster Anju Singh clearly recollects the message she delivered to camera when unexpected heavy rains started pounding and destroying crops in parts of India.

“We convinced farmers to do water harvesting, so at least water was not wasted and could be used later when there is scarcity,” Singh told DW. “Because the pattern has totally changed.”

As has the job of a weather forecaster. When she started out almost 15 years ago, “the role of weather presenters was just to talk about the weather forecast,” Singh said. “But now they are educators and a kind of bridge between (the) masses and the scientists.”

She is a senior presenter at DD Kisan, the agriculture television channel with India’s public service broadcaster Doordarshan. She’s also a member of Climate without Borders, a global network of weather presenters from more than 100 countries pushing to include more climate change talks in their daily work.

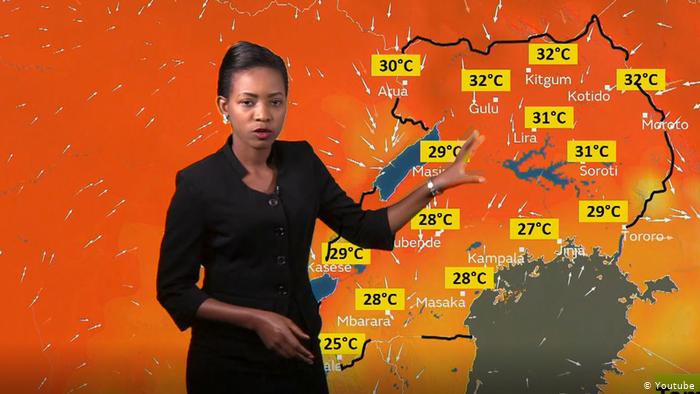

Kenyena Mollen, another member and weather presenter at the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (pictured above) says there is plenty of work to be done.

“We’ve seen there have been extreme events that weren’t there in the past,” she told DW. “Yet the public is not aware of such information.”

That’s where people like her and Singh can make a difference.

“TV meteorologists are unique in that they have an ongoing conversation with the public,” Bernadette Woods, Emmy Award-winning meteorologist and director of Climate Central’s Climate Matters program, told DW. “In many cases, they’re the only scientists the public ever sees.”

Climate Matters provides tools that enable meteorologists and journalists to better inform the public about the impacts of global warming. In 2017, they partnered with the World Meteorological Organization in a campaign to engage weather presenters and climate communicators.

Farmers as the target group

While for many people around the world, weather watching might be about deciding on how to dress or what to do on a given day, for those living from the land, forecasting can make the difference between saving the crop by harvesting earlier than planned or letting the rain spoil it.

Nonetheless, in India, where agriculture employs almost 60 percent of the country’s workers, Singh says convincing farmers about the perils of global warming is hard work. The most effective way, she adds, is to alert them to correlations.

Burning crop residues, for instance, leads to heat accumulation in the atmosphere and produces polluting smoke that may affect farmers’ health.

“We have to think of smarter ways of communicating and convincing people,” Singh said.

Woods agrees: “We’ve got this big global issue, but we feel it locally. So when you can make that connection, it’s pretty powerful.”

More time, more science

Extreme weather events, which Woods says are how most people now experience climate change, can help weather forescasters raise the issue.

“We know that climate change is changing our weather and that gives the opportunity for the TV meteorologists to make those connections for their public,” Woods said.

“For example, when there’s a heavy rain event or when heat is breaking records, they can really tie that to climate science.”

In the case of heat waves, for example, the link with climate change is usually relatively easy to explain. But as Friederike Otto, acting director of Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute, explains, most extreme weather events respond to a much more complex combination of factors.

And that makes the job trickier. “It’s a challenge to provide accurate climate change information that is visually appealing, and that you can talk about in five minutes or less,” Otto said.

As far as she’s concerned, an ideal weather forecast would not offer pure facts, but bring science closer to the public. At the same time, providing the audience with a solid scientific basis would enable them to correctly interpret the facts and figures related to weather and climate change.

Mollen is no stranger to the reality of short airtime, and would also like weather forecasters to receive financial freedom to spread the message in person among the country’s less privileged.

“As weather presenters we should be able to go out in the field and reach out to people unable to watch TV or even unable listen to radio,” she said. “Making the public aware is the best way to achieve the change we all seek.”

Taking the politics out of the weather

One freedom Mollen enjoys though is the fact that weather presenters in Uganda are not under political pressure when it comes to reporting on climate change. The same goes for India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi strongly supports a national shift toward sustainability.

“Now in India, the government is very conscious about it [climate change],” Singh said. “And weather presenters are considered an important part of this whole movement.”

That isn’t the case in the US, however, where Woods says “the biggest challenge” weather forecasters currently face is that climate change “has become a political issue.”

But she, together with hundreds of TV weather forecasters from around the world, is doing her best to move the issue out of the political arena and put it more squarely in the spotlight.