Since the Institut d'Egypte burned down in December during clashes resulting from a sit-in by the cabinet being violently dispersed by police, people have been concerned about the national treasures of rare books damaged by the fire.

Few knew of the books hosted in the historic building, except for the famous “Description de l'Égypte” (Description of Egypt). Thankfully, several copies of the 20-volume book written by a team of French scientists who accompanied Napoleon Bonaparte during his invasion of Egypt (1798 – 1801) lie safely in the country’s old libraries. Several more important, yet less known, books, however, have been tragically damaged. And at Dar al-Kotob (The National Library), where the books have been moved, conservators continue to work diligently.

“More than 10,000 books have been completely burnt,” says Dar al-Kotob Director Zain Abdul Hady. About 20,000 books were damaged by the fire and water, while another 20,000 arrived in good shape, he adds.

“This is one of the largest book restoration initiatives that have taken place in modern times,” says Abdel Hady, adding that it's even more difficult than the major flood of the Arno River in 1966 that damaged nearly one-third of the holdings at the National Central Library of Florence, which consisted of about 25,000 books including, most notably, its periodicals and Palatine and Magliabechi collections.

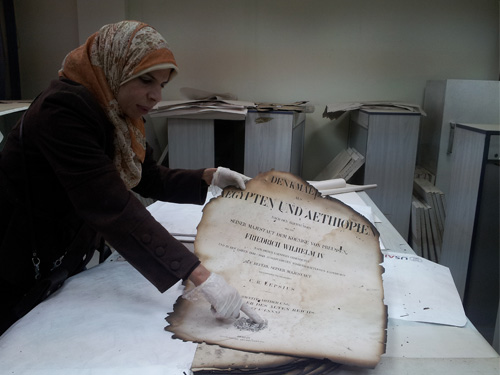

Among the rare books which were damaged is “Denkmäler Aus Aegypten Und Aethiopien”(“Monuments From Egypt And Ethiopia”), a massive 12-volume compendium.

Around 900 plates show ancient Egyptian inscriptions with commentary and descriptions made by a group of German Egyptologists headed by Karl Richard Lepsius. These plans, maps, and drawings of temple and tomb walls remained a primary resource for Western scholars well into the 20th century. But, they are also useful today, as they document monuments that have since been destroyed or re-buried.

For example, the book mentions a “Headless Pyramid” in the Saqqara area that is believed to house the tomb of King Menkauhor. Archaeologists could not locate it until May 2008, when a team led by Zahi Hawwas removed a 25-foot-high sand dune to re-discover the pyramid.

The book was donated to the Scientific Institute by Prince Mohamed Ali Tewfik, and was dedicated to Frederick William IV, the King of Prussia who had sent the archaeological mission to explore antiques on the Nile banks all the way from Cairo to Ethiopia in 1842.

“Monuments From Egypt And Ethiopia” was unfortunately severely damaged by the December fires. “It was damaged by the fire, the water used to extinguish it, and the rubble when the institute’s roof collapsed after the fire,” says Hanan Khodeir, a restoration researcher at Dar al-Kotob.

The book’s colorful plates faded from the heat of fire, but the harder part according to Khodeir came when volunteers used water to extinguish it, mixing the ink with the rubble on the surfaces of the pages.

The pages of “Monuments From Egypt And Ethiopia” arrived to Dar al-Kotob scattered between several packs of paper; Khodeir and her team started collecting them according to the similarities of damage. They did not know of the book at the time. But, they developed a plan, asking for the help of German, French, Italian and Spanish translators to sort out the pages once they have been dried.

The sorting committee then compares the papers that were found to the Scientific Institute’s database, as well as available copies elsewhere around the world. They, then, arrange them according to the book’s content.

"We will start to work on restoring the book to its scanned photo (if the book existed in any other library) or the imagined model that the sorting committee will come up with," Khodeir says.

Khodeir and her team started drying the books once they arrived at Dar al-Kotob using strongly absorptive paper sheets (those used for newspapers) and packaging the books using airtight plastic bags. “Otherwise, the books would rot, [and] we would have no chance of saving them,” she explains.

Over the past few months, work shifts have been doubled at the library to speed up the process, exchanging the wet sheets with dry ones until the book pages are totally free of moisture.

The huge number of damaged books pushed them to use printed newspaper sheets, risking the ink of the newspapers sticking to the books, until some local newspapers donated plain sheets.

Abdel Hady is working with three evaluation committees: Dar al-Kotob restoration experts, the Islamic Treasure Foundation, and an Italian committee headed by Mahmoud al-Shaikh, professor of manuscript at Florence University. They recommended the disposal of books that have been completely burnt.

That means they must get rid of an unidentified book containing wonderful paintings of Ottoman fashion designs and Urdu language, as it is completely burnt.

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) by Leonardo da Vinci is a book with more fame and fortune; with its 12 volumes, bound set of drawings and writings by Leonardo da Vinci. It comprises 1,119 leaves dating from 1478 to 1519, with the contents covering a great variety of subjects including flight, weaponry, musical instruments, mathematics and botany. This codex was gathered by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni in the late 16th century.

Khodeir only recognized the name of Leonardo da Vinci and accordingly classified the book as an important one. She explains that the book had two kinds of damage: its edges were burnt and rubble sticks to front page and some inner pages.

According to Abdel Hady, this means that the book will also need to be disinfected as all of the books at the institution have not been restored since it was built in 1798; so even the survived books will need to be restored.

“We need 15 years of hard work and LE100 million to restore the institution to the best possible condition,” says Abdel Hady.

He had directed Dar al-Kotob's entire budget to the books’ restoration, but he is also trying to reduce the budget. They started to experiment with manufacturing the restoration sheets locally instead of importing them as every sheet costs LE80. Using cotton, wood pulp and linen they started to make samples to submit to the three committees for approval.

Abdel Hady describes the restoration process as “huge, yet unavoidable,” saying he has to make difficult choices in order to save the books. He expects that no one can save all the 55,000 books that have arrived at Dar al-Kotob since 17 December.

The less complex restoration of the building itself is almost finished, according to the state-run daily Al-Ahram. The restoration was undertaken by Arab Contractors in a mission that spanned 100 days. Shelves have also been restored, awaiting the return of salvaged books, in an incident that awakened many to the limited access and knowledge surrounding relics like the books of the Institut.