DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — Efforts by the United Arab Emirates to fight the coronavirus have renewed questions about mass surveillance in this US-allied federation of seven sheikhdoms.

Experts believe the UAE has one of the highest per-capita concentrations of surveillance cameras in the world. From the streets of the capital of Abu Dhabi to the tourist attractions of skyscraper-studded Dubai, the cameras keep track of the license plates and faces of those passing by them.

While heralded as a safety measure in a country so far spared from a major militant attack, it also offers its authoritarian government means to track any sign of dissent.

“There is no protection of civil liberties because there are no civil liberties,” said Jodi Vittori, a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace who studies the UAE.

Dubai and Emirati government officials did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The UAE’s surveillance state can offer the parlor trick of finding your car at the massive, multistory parking garage of Mall of the Emirates, home to an indoor ski slope. But multiplied across the cameras watching public spaces, buses, the driverless Metro, roadways, gas stations and even all the emirate’s more than 10,000 taxi cabs, authorities in effect can track people in real time across Dubai. Police also easily gain access to surveillance footage from state-linked developers and other buildings.

A decade ago, Dubai proved those cameras could be quickly used. After the Jan. 19, 2010 assassination of Hamas commander Mahmoud al-Mabhouh at a Dubai hotel, police quickly pieced together the some three-dozen suspected Israeli Mossad operatives who carried out the killing. They later showed video beginning from the operatives’ arrival at the airport to their trailing of al-Mabhouh while dressed as tennis players.

State-linked media at the time suggested some 25,000 cameras watched Dubai. Today, cameras are far more sophisticated and far more prevalent. Technology as well has made the tracking even easier.

Since late 2016, Dubai police have partnered with an affiliate of the Abu Dhabi-based firm DarkMatter to use its Pegasus “big data” application to pool hours of surveillance video to track anyone in the emirate. DarkMatter’s hiring of former CIA and National Security Agency analysts has raised concerns, especially as the UAE has harassed and imprisoned human rights activists.

In the run-up to the pandemic, Dubai police launched a new surveillance camera program powered by artificial intelligence called “Oyoon,” or “Eyes” in Arabic. Police described the project in January 2018 as a means to “prevent crime, reduce traffic accident related deaths, prevent any negative incidents in residential, commercial and vital areas and to be able to respond immediately to incidents even before they get reported.”

The “Oyoon” project included police partnering with government and semi-government businesses that already had a vast network of surveillance cameras.

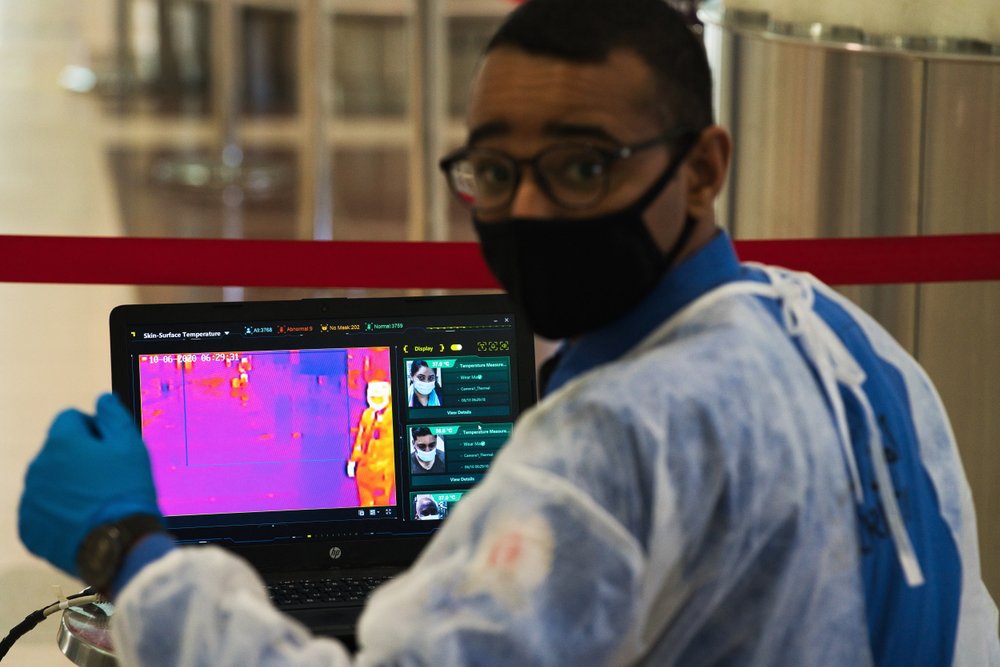

In May, Dubai police Brig. Khalid al-Razooqi said the “Oyoon” system would begin checking temperatures of those passing by, as well as making sure people maintain a social distance of 2 meters (6 feet) from each other.

Outside of “Oyoon” cameras, Dubai police also are experimenting with thermal helmet cameras for officers to check passers-by’s temperatures. Malls and other business have implemented a variety of thermal image scanners. At Dubai International Airport, for instance, those coming in walk past a thermal scanner that also checks people for masks. Dubai’s Silicon Oasis neighborhood similarly has been tracking passers-by with cameras.

Similar technology has been used at the Mall of the Emirates, run by the private firm Majid Al Futtaim. Companies building so-called “disinfection gates,” which fog chemicals on people, similarly use thermal cameras that also can record and upload their data.

Nothing prevents these additional cameras and their data from being fed into wider facial recognition databases in the city-state. The UAE already has such a database from its national ID card system, which residents use for fast immigration clearance at Dubai International Airport.

Meanwhile, the UAE’s capital Abu Dhabi is believed to have its own extensive security camera system. Other emirates as well have touted their camera networks, with the emirate of Ras al-Khaimah announcing in February it installed over 140,000 cameras itself.

This comes as the UAE bans political parties, labor unions and strikes by its foreign laborers — all while commemorating 2019 as its “Year of Tolerance.” Laws in the Emirates also give authorities broad latitude to punish people’s speech, while docile local media remain largely state-owned or government-linked.

“Dozens of activists, civil society leaders, academics and students remained imprisoned during 2019 as part of the broader crackdown,” the Washington-based advocacy group Freedom House said in its recent annual report on the UAE. “The political system grants the Emirates’ hereditary rulers a monopoly on power and excludes the possibility of a change in government through elections.”

Many of the cameras and thermal scanners used by the UAE come from China. A Chinese firm also announced a deal for coronavirus vaccine trials in Abu Dhabi, a deal it struck that included Group 42, a new Abu Dhabi firm that describes itself as an artificial intelligence and cloud-computing company. Also known as G42, the company’s CEO is Peng Xiao, who for years ran Pegasus, the DarkMatter “big data” software.

G42 has partnered with Israeli firms over the coronavirus. It also partnered with China in order to handle the UAE’s mass coronavirus testing program. US Embassy officials in Abu Dhabi earlier declined an Emirati offer to test all American personnel for free due to Chinese involvement in the program, something first reported by The Financial Times.

China’s involvement would raise security concerns for US forces operating in the UAE, said Vittori, a retired lieutenant colonel in the US Air Force. The Emirates, nicknamed “Little Sparta” by former US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, is home to some 5,000 American troops, many at Al Dhafra Air Base. It also hosts the busiest port for the US Navy outside of the United States at Dubai’s Jebel Ali port.

“Having ‘Little Sparta’ with the Chinese surveillance network should be a concern to United States,” Vittori said.

___

Image: FILE – In this June 10, 2020 file photo, an official wearing a mask due to the coronavirus pandemic operates a temperature screening point at Dubai International Airport’s Terminal 3 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Efforts by the United Arab Emirates to fight the coronavirus have renewed questions about mass surveillance in this U.S.-allied federation of seven sheikhdoms. (AP Photo/Jon Gambrell, File)

Follow Jon Gambrell on Twitter at www.twitter.com/jongambrellAP.