Pressuring teens to get fit is counter-productive, according to a new study that suggests they are more likely to exercise if they feel in control of their choices.

The research team recruited participants of approximately 13 years of age because it’s just before this point — when they are around 10 — that kids are believed to decrease their activity levels by 50 percent.

“Our results confirm that the beliefs these kids hold are related to physical activity levels,” says lead author Rod Dishman, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Georgia. “But can we put these children in situations where they come to value and enjoy the act of being physically active?”

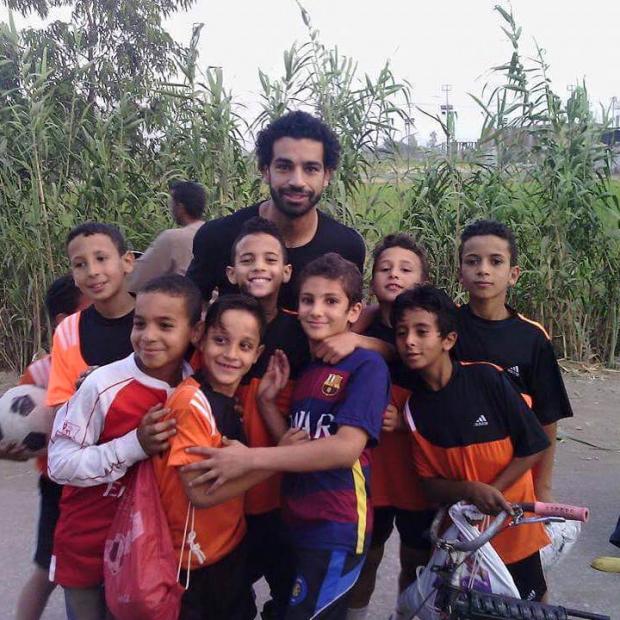

Helping kids identify with exercise at a younger age could be one solution, says Dishman, with the goal of them reaching middle school and considering themselves to be fitness-savant.

More structured games during the early years that integrate exercise into academics or increasing efforts to create community sports leagues are in store, according to Dishman.

“Just like there are kids who are drawn to music and art, there are kids who are drawn to physical activity,” he says. “But what you want is to draw those kids who otherwise might not be drawn to an activity.”

Shame is not the answer, according to the study, which overwhelmingly found teens were less likely to exercise out of pressure to do so.

“The best thing is to do it because it’s fun,” says Dishman. “It’s the kids who say they are intrinsically motivated who are more active than the kids who aren’t.”

Published in the journal Medicine & Science In Sports & Exercise, the study follows on the heels of research conducted in the UK that suggests making a special effort to motivate young teens to exercise could cut their risk for diabetes.

The researchers measured the insulin resistance of 300 youngsters every year starting when they were nine years old until they turned 16.

Type 2 diabetes was 17 percent less likely to occur in the more active participants by the time they turned 13, regardless of their body fat levels, according to the study.

According to the study, 13 is the age at which incidence of type 2 diabetes peaks, and unsurprisingly, the 17 percent advantage dwindled progressively until participants turned 16, indicating the need to start exercising at a younger age.

“Insulin resistance rises dramatically from age 9 to 13 years, then falls to the same extent until age 16,” says study author Dr Brad Metcalf, of the University of Exeter. “Our study found that physical activity reduced this early-teenage peak in insulin resistance but had no impact at age 16.”