It is 7:30 pm in Hadeyek al-Qobba Square, named for the popular neighborhood in north Cairo where it is located. Cars flock to the bus station in the heart of the square with co-drivers popping out to call on passengers. A mixture of men walk by, some in traditional robes and slippers, reflecting their rural backgrounds, while others prefer shirts and jeans. The same variety is apparent among the women, some of whom are in black robes and cover their faces, while others wear colorful headscarves tied to the back of their heads.

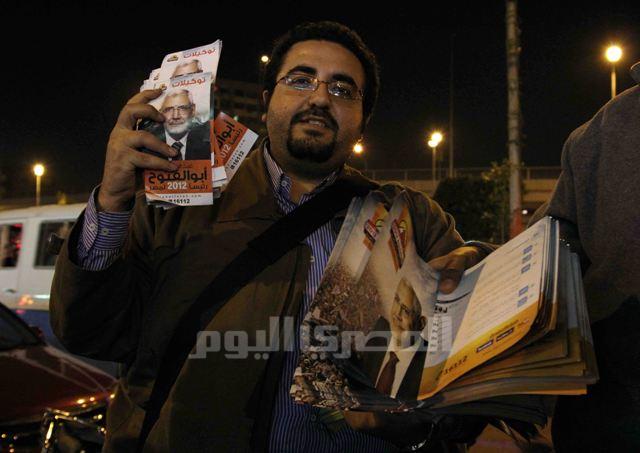

In the background, a nearly one meter-long orange banner dangles from the top of a flyover that links the area to the upper-middle-class neighborhood of Heliopolis, bearing the photo of presidential hopeful Abdel Moneim Abouel Fotouh. Not too far from this political advertisement, a dozen enthusiastic young men, mostly in their 20s, convene. In less than 30 minutes, they will conquer the neighborhood on a political mission.

“We are the Free pro-Abouel Fotouh Campaign. We are today in Hadayek al-Qobba,” announces 29-year-old Mohamed al-Nahhas in a fervent tone, as if he were a battalion leader seeking to mobilize his soldiers. “We will be divided into groups of five. What we do here is make people more aware of Abouel Fotouh.”

This is the youth-led campaign that kicked off last month to rally support for the 60-year-old potential presidential contender independently from his official run. Tired of the formalities and the centralized politics of conventional campaigns, less than ten revolutionary young men took it upon themselves to launch a more spontaneous and aggressive campaign that can achieve a larger and quicker outreach.

Decentralized and diffuse

“There is a huge difference,” Nahhas, a co-founder, tells Egypt Independent of his campaign and the official one, as he walks down the street handing out flyers.

“The main centralized campaign is concerned with conferences and the media, but we hit the street. It is true that official campaigners hit the street too, but not as much as we do and not with the same logic. We seek to build an intimate relationship with people.”

So far, Nahhas has collected an email list of 300 potential volunteers in Cairo alone. Ahead of every tour, Nahhas circulates the details, and different faces always show up. The campaign arranges five evening tours a week, each lasting almost three hours. When volunteers sense that Abouel Fotouh has no significant following in a particular neighborhood, they arrange second and third visits.

Initially named “Abouel Fotouh's cafes,” the campaign has been invading coffee shops in popular areas, the main evening hub for many men, to promote Abouel Fotouh. They then expanded their operations to movie theaters, restaurants and metro stations, according to one of the founders.

Most volunteers have had experience in other political campaigns, such as the No to Military Trials campaign that sought to raise discontent against the referral of civilians to military trials and “Kazeboon (Liars)” in which activists toured the country to display videos exposing military brutalities. Others had accumulated the expertise through their involvement in the April 6 movement and the pro-Mohamed ElBaradei campaign.

Basem Fathy, 27, belongs to the latter group, who dared to defy Hosni Mubarak by calling for civil disobedience and arguing that political reformist ElBaradei should replace Mubarak.

Based on his previous activism, Fathy contends that most political campaigns lacked the genuine interest in reaching out to large segments of society or acting vigorously on the street.

“They are isolated in cyberspace and when they transcend this isolation, they go to television channels that are mainly watched by [the same audience],” says the graduate of Cairo University's school of natural sciences.

“Our goal was to break that pattern and reach out to people directly,” says Fathy, one of the active members in the campaign.

Given their revolutionary nature, these youths refused to abide by the bureaucratic rules and the hierarchical nature of Abouel Fotouh's official campaign.

“Any official presidential campaign is a bit bureaucratic and centralized by default,” says Mohamed Atef, one of the Free Campaign's founders. “To make a decision, one has to wait for his immediate leader, who in turn has to refer the matter for whoever is above him.”

“The point was to be free and not to be linked to the centralized campaign,” adds the 23-year-old lawyer, whose campaign has no hierarchy or no strictly-observed schedule. Sometimes the details of a visit are announced less than 24 hours ahead of time. For campaigners, this spontaneity is more efficient and less costly.

After ElBaradei, Abouel Fotouh

The Free pro-Abouel Fotouh campaign includes youth who initially backed ElBaradei, whose anti-Mubarak campaign kicked off in early 2010.

For most revolutionaries, ElBaradei’s support of democratic demands and sharp political outlook are beyond doubt. However, they have always complained about his reluctance to engage in aggressive presidential campaigning on the street.

“I still find ElBaradei a respectable man but I believe he has a problem in reaching out to people,” says Fathy, who withdrew from ElBaradei’s campaign in May 2010.

Yet, others had drifted away from the Nobel Laureate only few months ago.

“I supported ElBaradei until the time of Mohamed Mahmoud clashes,” says Islam Abouel Azm, only few minutes before the expedition into Hadayek al-Qobba takes off. “He had a weak position then. He did not go to the (Tahrir) Square during the clashes. He did not do anything other than write tweets.”

In November, clashes erupted between protesters on one hand and the police and the military on the other. Dozens were killed in the stand-off that lasted for five days on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square. All ElBaradei's statements were firmly supportive of the protesters, but he did not head to the square until the violence ceased. Back then, he announced that he was willing to give up his candidacy for the presidency and form a national salvation government that would rule for the rest of the transitional period. Yet, neither Islamists nor the generals heeded the call.

In January, the 70-year-old former diplomat dealt a blow to the generals by announcing his withdrawal from the presidential race set for 23 and 24 May arguing that he could only run under a genuinely democratic system.

For Abouel Azm, a 26-year-old road engineer, Abouel Fotouh was the second best choice, not for the simple reason that he had shown up to the field hospital set up near the scene to rescue the victims of Mohamed Mahmoud clashes, but because of his critical views of the SCAF’s performance and his moderate political outlook that distinguished him from other Islamists.

“I felt encouraged to back him after I learned that he represented the reformist trend within the Muslim Brotherhood and had engaged in huge fights for that with the group,” says Abouel Azm.

Beyond Islamists

Many of these pro-Abouel Fotouh volunteers don’t identify as Islamists. In fact, some consider themselves as hardcore secularists.

“I am fully secular, and I totally believe in the full separation between religion and politics,” says Fathy. Yet, Abouel Fotouh's Islamist background does not seem to bother him. “What I care about is to have my liberties protected and I believe they will be under Abouel Fotouh. I do not care what political background he has.”

“I find [Abouel Fotouh] the most suitable president because he is moderate, he is not extremist. In the meantime, he is accepted by the people because he is not tainted with secularism,” he adds.

Secularism is something of a notorious term in the mind of the Egyptian electorate. It is widely held as the equivalent of atheism by a religious voting public.Since Mubarak's ouster, ideological feuds between secular and Islamist parties have been brewing, with the latter always winning voters on their side thanks to their discourse that portrayed their secular adversaries as anti-religious.

In the meantime, secularists responded by arguing that Islamist groups seek to form a theocratic government. Abouel Fotouh has been marketing himself as the missing link between the two camps. The former leader of the Muslim Brotherhood takes pride in his Islamist background and also fully embraces democratic values and individual liberties. In fact, Abouel Fotouh adopted this progressive discourse long before the revolution, outdoing most Brothers, which led to his marginalization within the group since late 2009.

After the revolution, he provided the Muslim Brotherhood's hawks a perfect pretext to expel him when he announced that he would run for president. His announcement was seen as a violation of the group's decision not to field any candidate for the presidential race. In July, the Muslim Brotherhood's Shura Council dismissed him from the 84-year-old Islamist organization.

Despite their commitment to the campaign, not all volunteers are confident that Abouel Fotouh will win. Some even fear that the vote will be rigged in favor of the candidate backed by the ruling military council.

Although the parliamentary vote was widely hailed as fair, there are doubts that the generals will ensure the same level of integrity in the presidential poll, which is scheduled to take place on 23 and 24 May.

“I will support Abouel Fotouh until the last minute, but I do not expect him to win,” says Abdallah Abbas, a 25-year-old graduate of Ain Shams University's school of engineering. “This is not because he is a bad candidate but because the poll will not bring anyone to power who can really benefit the country.”

“The one who steals and kills would not bring to power someone who can hold him accountable for what he did,” says Abbas, referring to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces.