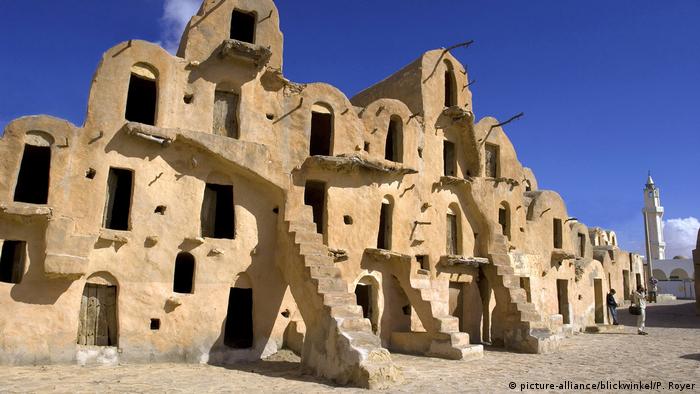

For 10 years, Juanita Reimer has lived at the edge of the Sahara desert in Douz, Tunisia. Since leaving her home in Canada, she has been working Berber and Bedouin families to show visitors a side of life in the country most never see: from the vaulted granaries in the towns of Tataouine, inhabited since the 12th century, to the pitted cave homes of her friends, dug directly down into the earth.

In those ten years she has seen those families, for whom tourism is vital, take knock after knock: First, the 2011 revolution that sparked the Arab Spring scared many tourists off. Then in 2015,two terror attacks at beach resorts in the UNESCO listed city of Sousse in the central-east decimated the industry. In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic came.

“It was really, really hard and still is,” Reimer said. “After the revolution and the terrorist attacks, a lot of people had to sell their camels, which was really tragic. Now, many people have just gone off into the desert with their animals and families to supplement the animals’ food with whatever grows there.”

But after a three-month lockdown, the country has recorded zero local cases for almost a month and will be the first nation in the North Africa to reopen its borders, on June 27.

In Sousse, Osama Mani, who handles reservations at a major upscale hotel, said locals who rely on tourism were trying to get back on their feet.

“We were expecting a good year, a good season of tourism. But the coronavirus felled these hopes and crushed them,” Mani said. “We are dealing with it step by step now and have brought in a health protocol. Because Tunisia is winning against the coronavirus, I think it will be a good destination for people from all over the world.”

While many other countries continue to struggle against the virus, Mani said Tunisians put down their success in keeping cases of the virus low to their spicy harissa and olive oil.

Tight restrictions see positive results

Tunisia has seen encouraging numbers and it needs them: Tourism accounts for 10% of its GDP and the economy is expected to shrink by 4.3% due to the virus, the steepest drop since independence in 1956.

With only 1,087 confirmed cases as of Friday, June 12, it has seen no new local positive tests since May 19 and no imported cases since June 2, according to World Health Organization (WHO) spokesperson Inas Hamam.

The WHO praised the country’s early surveillance, tracing and quarantine measures and a comprehensive lockdown introduced in March, when the number of confirmed cases was less than 100, Hamam said. By comparison, Italy did the same when its numbers were at 10,000.

“I think two reasons why countries like Tunisia have done better is: one, people here don’t have a sense of entitlement. They respect the curfew, they get it,” Reimer said. “The other thing is they have a sense of community. They don’t just say, ‘I want to go out,’ no, it’s like ‘maybe I won’t get sick but there’s people in my village who are older.'”

A way to go on distancing

But even with so few cases, the government has not considered declaring the country “coronavirus free,” Hamam said.

The government still classifies the state of control of the virus as the WHO’s most serious standard, “community transmission”, meaning widespread, unchecked and uncontrolled.

According to Hamam, this doesn’t reflect the situation. But authorities are being cautious about easing restrictions while many people are not respecting safe behaviors such as wearing masks and physical distancing, she said.

One local handball referee, Abdelhak Etili, noticed this early on, taking it upon himself to hand out red and yellow cards to those not keeping a safe distance.

Increasing frustration

The government’s attempt to balance restrictions and the economy also reflects a nervousness about its power.

In April, authorities arrested two bloggers who had criticized the government’s handling of compensation for struggling families, echoing some of the conditions that saw the previous regime ousted and uprisings spread across the region in 2011.

In fact, protests in seven cities across the country in late May demanding jobs and an end to the country’s stubborn high unemployment added to sentiments in some quarters that things are now worse than they were before the revolution.

Caught in two minds

Mohamed Karmani, who runs a jewelry and crafts shop in the climbing stone lanes of Sousse’s heritage-listed Medina quarter, said business had gotten worse since 2011. However, he was still hesitant about reopening the country.

“I want the tourists to come here, but maybe they will bring the virus with them. I want the country to make special preparations so we can know these tourists are healthy and not coming here with the virus,” he said.

Whether Tunisia’s tourism industry recovers soon also partly depends on when European countries decide to relax restrictions on those travelling abroad.

On the edge of the Sahara, Reimer said her friends are holding out “cautious hope.”

“One person told me, ‘Damn it, of course we have to shut [the business],'” she said. “They don’t want to lose their families either, they realize the dangers.”