TUNIS (Reuters) – Tunisians voted for a new parliament on Sunday but quiet polling stations gave an indication of the economic disillusionment that has emerged since the 2011 revolution and brought political newcomers to challenge established parties.

By 11:30 am, turnout across the country was only 6.85 percent, the electoral commission said, compared to 7.3 percent at the same stage of last month’s first-round presidential election, in which only 45 percent of registered voters cast ballots.

The failure of repeated coalition governments that grouped the old secular elite and the long-banned moderate Islamist Ennahda party to address a weak economy and declining public services has dismayed many Tunisians.

“After the revolution, we were all optimistic and our hopes were high. But hope has been greatly diminished now as a result of the disastrous performance of the rulers and the former parliament,” said Basma Zoghbi, a worker for Tunis municipality.

Unemployment, 15 percent nationally and 30 percent in some cities, is higher than it was under the former autocrat, Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali, who died last month in exile in Saudi Arabia.

Inflation hit a record 7.8 percent last year and is still high at 6.8 percent. Frequent public sector strikes disrupt services. Financial inequality meanwhile divides Tunisians and the poverty of many areas has become an important political theme.

Any government that emerges from Sunday’s election will face the competing demands of improving services and the economy while further reining in Tunisia’s high public debt, a message pushed by international lenders.

While the president directly controls foreign and defense policy, the largest party in parliament nominates the prime minister, who forms a government that shapes most domestic policy.

For weeks, the names and faces of candidates have been posted on the walls of schools, which double as polling stations on election day, and leaflets have been stuffed through mailboxes or under car windscreen wipers.

However, at four polling stations visited by Reuters on Sunday, there seemed to be few younger voters.

One of them, Imad Salhi, 28, a waiter, was concerned about the direction of Tunisian politics. “I am very afraid that the country will fall into the hands of populists in the next stage,” he said.

POLITICAL NEWCOMERS

Sunday’s vote for parliament is sandwiched between two rounds of a presidential election in which turnout has been low and which advanced two political newcomers to the runoff at the expense of major-party candidates.

It is not clear what that may mean for Sunday’s election, in which Ennahda is one of several parties hoping to emerge with most votes, including the Heart of Tunisia party of media mogul Nabil Karoui.

Weeks before the presidential vote, Karoui was detained over tax evasion and money laundering charges made by a transparency watchdog three years ago, which he denies, and has spent the entire election period behind bars.

However, his success in the first round of the presidential election along with the independent Kais Saied, a retired law professor with conservative social views, has put pressure on the established parties.

Saied has suspended campaigning, saying he does not want to gain an unfair advantage over Karoui, who has not been able to meet voters or give any interviews so far from his cell.

If no party emerges as the clear winner on Sunday, it could complicate the process of building a coalition government.

Reflecting the uncertain atmosphere, Ennahda and Heart of Tunisia have sworn not to join governments the other is part of, a stance that bodes ill for the give-and-take vital to forming an administration.

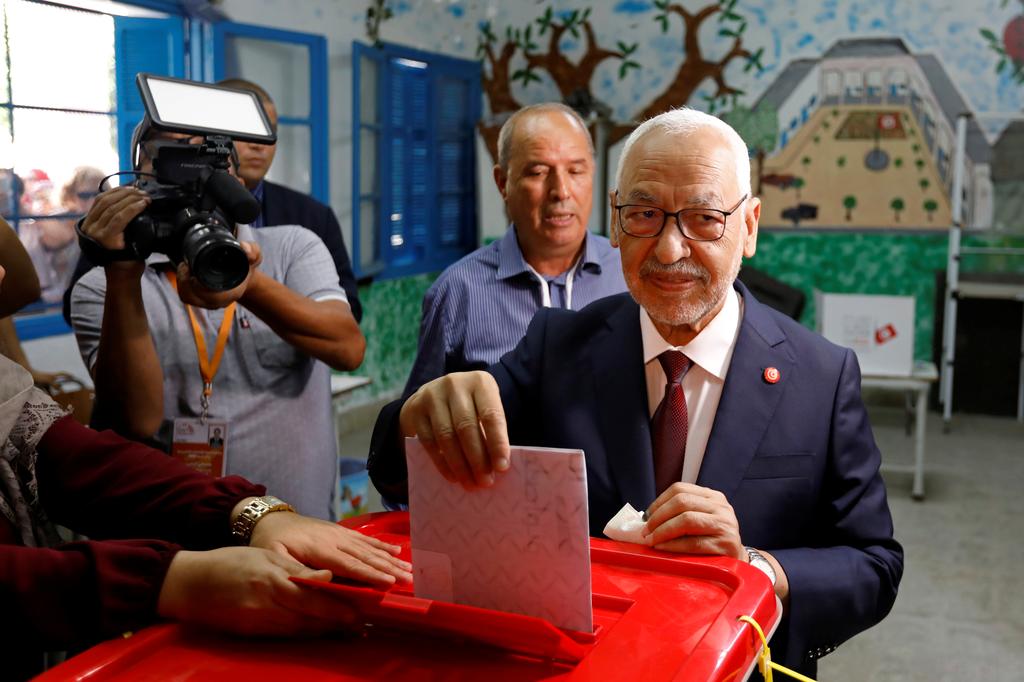

“Tunisians should be proud for their democracy but the focus should be on economic and social conditions of Tunisians,” Ennahda leader Rached Ghannouchi told Reuters after voting in Tunis.

Local monitoring groups reported some voting irregularities on Sunday, alleging some voters may have received money from parties or candidates. Ennahda urged the electoral commission to investigate.

If even the biggest party fails to win a large number of seats, with many independents standing, it may struggle to build a coalition reaching the 109 MPs needed to secure majority support for a new government.

It has two months from the election to do so before the president can ask another party to begin negotiations to form a government. If that fails, the election will be held again.

Reporting by Tarek Amara and Angus McDowall; Editing by Alison Williams

Image: Rached Ghannouchi, leader of Tunisia’s moderate Islamist Ennahda party, casts his ballot at a polling station during the parliamentary elections in Tunis,Tunisia October 6, 2019. REUTERS/Zoubeir Souissi