While the majority of former officials' trials since the outbreak of the revolution have been related to financial corruption, Egypt’s Treason Law – used to try political officials after the 1952 Free Officers coup – is providing an alternate, and controversial, path for prosecuting those implicated in various forms of corruption.

Crimes punishable under the Treason Law 344/1952 include a government official’s abuse of power for his or her own interests, or for the interests of any company, institution, public authority or body. It also encompasses financial crimes including directly or indirectly influencing the increase or decrease in the price of property goods, crops, prices of securities or other government or financial securities listed on the stock exchange and in the markets, for his or her personal benefit.

Government officials may also be punished for abusing their power to achieve a job or higher status for themselves or others.

The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies said this week that it opposes the use of the Treason Law, instead voicing support for “a bill [to] be swiftly drafted that includes the establishment of an independent judicial committee to authorize a program for transitional justice.”

Transitional justice refers to the ways in which countries prosecute past human rights violations.

A transitional justice initiative, which would require the establishment of a special committee or tribunal, has support from many in the human rights advocacy community, but could be more complicated than simply reactivating a 59-year-old law that was once used as its own method of transitional justice.

Bringing the Treason Law into force would require nothing more than a decree from the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, according to Tahany al-Gebaly, vice president of the Supreme Constitutional Court.

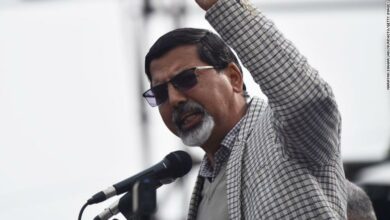

“The Treason Law is extremely relevant today because it brings in a whole other sphere of political corruption charges, which need to be assessed in the investigations of former regime members,” said Nasser Amin, the director of the Arab Center for the Independence of the Judiciary and Legal Profession.

In early June, Fekry Kharroub, former president of the Alexandria Judges Club and current president of the Supreme State Security Court, accused former President Hosni Mubarak of committing treason by attempting to transfer power to his son, Gamal.

“This same law would assess many other criminal charges, such as the role of Mubarak and former Interior Minister Habib al-Adly in ordering security forces to detain, torture and shoot at protesters during the revolution – a clear example of abuse of power – as well as many other corruption probes that extend beyond financial charges,” said Amin.

Mubarak is also being questioned for partaking in arms deals and issues related to “the interests and secrets of the armed forces.”

The Treason Law allows punishments ranging from removing the official from office, political parties, parliament and all state councils, to banning the convicted from running for election or being nominated to any government body or council for a minimum of five years from the date of the sentence, according to Court of Cassation President Ahmed Mekky.

More severe sentences can include imprisonment from three to 10 years and convicts can have their citizenship rights revoked.

But with questions about the ruling military council’s dedication to trying officials from the former regime, there might be a bigger problem with the Treason Law.

“In accordance with Article III of the law, although these court cases are overseen by three [civilian] judges, they are also overseen by four officers of the armed forces appointed by the commander of the armed forces,” Amin says.