Egyptian artist and professor Shady El Noshokaty is currently establishing an educational facility for young artists in Ard el Lewa, a populous, informal neighborhood west of Mohandessin. A number of artists live in the area, including Noshokaty, Magdi Mostafa, Ahmed Sabry, Ahmed Basiony and Hamdy Reda, who runs the Artellewa art space.

The space will open under the auspices of the newly-established Noshokaty Foundation for Contemporary Art Education, with plans to expand on Noshokaty’s existing summer workshops, while also hosting research projects and year-round weekly discussions, screenings and sessions with visiting artists.

Noshokaty has been teaching painting at Helwan University’s Faculty of Fine Arts Education for 15 years, and is currently also on staff at the American University in Cairo. Since 2000 he has been running month-long summer workshops in new media arts, graduating some of Cairo’s most ambitious and innovative young artists.

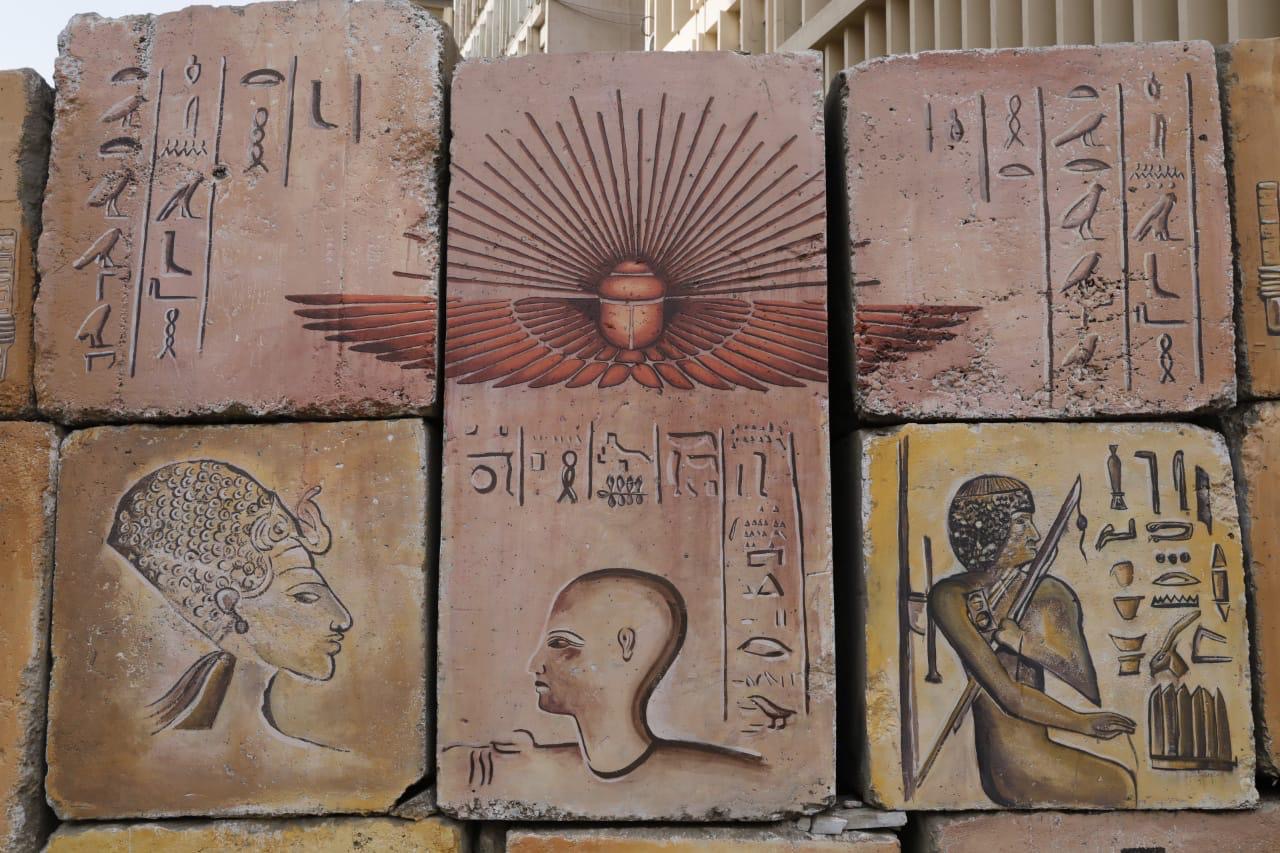

Motivating Noshokaty is his perception of a problem that has persisted in Egyptian art production since the 1920s: the importing of form rather than process. Egyptian artists educated in Europe during that period brought back the visual tropes of Impressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism, then inserted “Egyptian” motifs–Pharoanic designs, fellahin, Cairo street-scenes–which, Noshokaty says, “perpetuated a false identity, exotic and superficial.”

Artists must create their own language for art-making rather copying ancient styles which are now the world’s heritage, he argues. Since the 90s, Egyptian artists have started receiving international attention, something that Noshokaty attributes to the use of research, which he says is “a universal language."

Noshokaty’s workshops aim to run in parallel to both government institutions, which can be bureaucratic and seek to maintain the status quo, and alternative art institutions that are often funded though foreign grants and favor the English speaking elite. Because of funders’ expectations, such institutions tend to focus on the end product rather than the process.

Mohamed Abdelkarim, a multimedia artist and graduate of one of Noshokaty’s workshops, points out that these “two camps, middle and upper class, have totally different mentalities and agendas” and that affluent, English-speaking artists are better at writing proposals and getting support, allowing them to devote most of their time to art. Furthermore, according to Abdelkarim, art faculties at Egyptian universities refuse to teach new media.

Noshokaty prioritizes the large segment of the population who, because of financial constraints, have access to only government educational institutions, the curricula of which largely fail to incorporate contemporary art or encourage free creative thinking. He wants the foundation to reach out to both middle and upper class with their dissimilar understandings of art-making.

Noshokaty does not feel connected to zeitgeisty “alternative” arts education programs; he aims to compliment existing government university programs by turning students into researchers. “University art faculties focus on craftsmanship, which is useless without content.” Indeed, a preoccupation with language and self-discovery is also evident in his own artwork, such as the ongoing series Stammer which involves video, performance and sculpture.

Noshokaty’s workshops encourage analytical thinking, provide skills, and educate participants about new media art. Screenings have included downloaded versions of American artist Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle, documentation of exhibitions from Noshokaty’s travels, and David Lynch movies. Each screening is followed by a discussion.

Past workshops have created strong peer groups; many participants continue their conversations and some collaborate on establishing independent art organizations and exhibitions. “Each workshop has created its own Facebook group, where they have discussions,” reports Noshokaty, with a smile.

It is not unusual for students to attend consecutive workshops, with some going on to serve as instructors. Two former students, Ahmed el-Shaer and Hala Abushady, created classes in computer game art and video art, respectively. Other topics include performance, sound, and comic strip art.

Medrar for Contemporary Art, which organizes the annual Cairo Video Festival, new media workshops and an archive documenting the art scene, was founded by alumni of Noshokaty’s workshops. Former participants also put together the independent exhibition Cairo Documenta, which opens at the Viennoise Hotel this week in parallel to the 12th International Cairo Biennale.

For Abdelkarim, Noshokaty’s 2003 workshop was a turning point. As a student at the Faculty of Fine Arts Education at Helwan, he was making work he now calls “old-fashioned,” and was not interested in exploring new media. Abdelkarim spent that summer at home in Minya, making a sculpture to submit to the Youth Salon, the annual juried exhibition at the Palace of Arts. When the piece suddenly collapsed, a disappointed Abdelkarim returned to Cairo, where his friends persuaded him to attend the visiting artists’ talks at Noshokaty’s workshop.

“The first day it was Hassan Khan, the next Moataz Nasr and then Amal Kenawy,” he remembers. In one week, Abdelkarim says he went from “making art from a historical age” to embracing the contemporary. The resulting video was accepted at the Youth Salon.

The foundation space, which will host forthcoming workshops, currently consists of a 300 square meter empty basement, directly beneath a design studio run by Mohamed Taman and named after the Arabic letter noon. Noshokaty’s students will be working with the studio to produce a publication chronicling the workshops so far.

The space will be divided into a studio for Noshokaty, and space for the workshops: he aims to furnish it with four computers and a library. The proximity of his studio to the education space will facilitate an examination of the art-making process as part of the artists’ education.

Noshokaty plans to ask resident artists at galleries such as the Townhouse, Artellewa and the Contemporary Image Collective to speak there, rather than establishing a residency program for the foundation.

Noshokaty hopes that the foundation will attract not only art students but students from other faculties, such as music. Workshops will continue to be free and open with no selection process, and participants must bring their own equipment.

Funding will depend on the sale of Noshokaty’s own artwork. Another challenge will be attracting students to the new space. Previous workshops were held on Helwan University premises, lending the gatherings an official air that students and their parents trusted; the university also provided dorms for traveling students.

Visitors can familiarize themselves with the space at an art opening tomorrow evening at Artellewa, as Noshokaty has lent it for the group exhibition The One and the Multiple. The foundation itself will open in March.