What’s the first thing that comes to your head when you hear the word Bedouin? For many of us, it is a fairly predictable variation on hospitality, nomadic lifestyle, tradition and camels.

And if you go on a desert trip spending a few days with a Bedouin guide or guides, depending on how many you are, your associations with the word Bedouin are likely to remain pretty much the same.

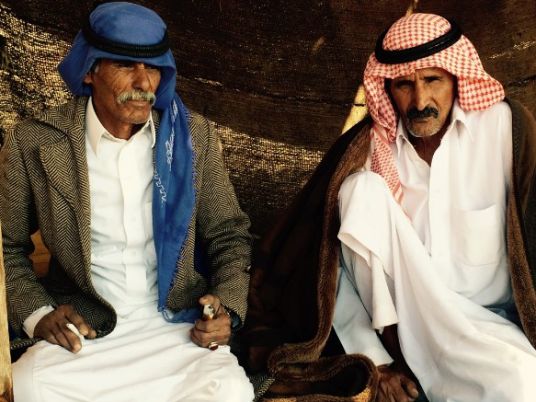

This is not because these associations bear a particularly close relationship to reality, but because they are produced and reproduced in all sorts of places, including tourism. Images like these of the Bedouin have long been present in art and literature, in state policy and now increasingly the tourism sector.

While the images associated with the Bedouin evoke an exotic timelessness, the touristic encounter is not one between a tourist and a Bedouin hailing from a community untouched by the passage of time, bumping abruptly into modernity.

What might be called a Bedouin economy has long been a mixed economy, combining pastoralism, animal herding, agriculture, trade and wage labor. Bedouins have not sat outside of history, but have been very much shaped by all sorts of forces, local and global, from colonial powers to newly formed nation states and government-sponsored development projects.

That this is so should hardly need saying, except that the Bedouin are still often viewed as somehow being beyond the clutches of history and time.

Egypt’s three deserts — the Sinai Peninsula, the Eastern or Arabian Desert and the Western or Libyan Desert — together make up most of the country’s territory, but hold a minority of the population. Until the mid-20th century, these deserts were administered separately from each other and it was not until the late 1940s that Bedouin received national identity cards and were brought into the army as Egyptian citizens.

Tourism in the desert

As we wandered through and around white rock formations of the White Desert — equally but differently beautiful in the bright daylight glare, the caress of the sunset and the surprisingly light moon of the early month — conversations with our Bedouin guide meandered.

Like many who work in the tourist industry, our guide was pretty scornful of the revolution. “Maybe other Egyptians might benefit but we didn’t need it,” he says, anxiously reiterating his concern that visitor numbers improve.

Meanwhile, Saad Ali, one of the co-founders of Badawiya travel agency, focuses his blame for dwindling tourism on President Mohamed Morsy. Both are concerned about buzzwords “security” and “stability,” so that their livelihoods can resume.

While tourism in general is down, Ali says there has been a 10 percent increase in Egyptian visitors, since other parts of the country generally popular with local tourists are gaining a reputation as unsafe.

The high season is from winter to spring, meaning that even when tourism is not down, those who work in the sector have to find other work for much of the year.

Our guide said he busies himself with odd jobs such as gardening, mechanics or carpentry when he does not have desert safaris, but is generally bored doing so.

And it is not just the desert guides.

“Several people’s livelihoods are affected by tourism, for example, even the local butchers who provide meat for safaris,” Ali says.

Guides and drivers receive training on how to safeguard the environment. Indeed, our guide left not a scrap of rubbish and seemed visibly upset when he saw a car giving its passengers a view from high on a rock formation — something he said was not allowed, as it is part of the White Desert protectorate.

The blurb on the Badawiya website reads, “Our philosophy is to protect the White Desert and at the same time to work on developing the Farafra Oasis community.”

Al-Hayah Farafra Development Association, co-established in 2004 by some of the co-founders of Badawiya, works on community development and seeks to use participatory methods to bring different parts of the community together, including women.

One of its initiatives, in collaboration with Badawiya, is a six-day trip once or twice a year to clear rubbish left behind by desert safaris and garbage scattered during the stormy season.

Although a number of funders are listed on Al-Hayah’s website, Ali explains the main source of funding for projects come from Badawiya's profits. An ailing tourism industry means fewer resources for these projects.

‘The native of the desert’

Desert safaris have become increasingly popular and central to this is the “native of the desert” — the Bedouin guide.

That the image of the Bedouin is being repackaged, commodified and sold in the tourism market is obvious from even a brief perusal of the desert safari websites. Take this one for instance: “In the Bedouin culture, the most important thing is the Guest. This has enabled the Bedouin to seamlessly integrate working in tourism with their culture and daily lives.”

This commodification of Bedouin identity can be seen across the region in Bedouin theme parks and villages, camel races, museum exhibits, poetry recitals and Bedouin culture festivals. In fact, in 2005, UNESCO observed that in Jordanian tourist spots Wadi Rum and Petra, “the increase of desert tourism and its demand for ‘authentic Beddu culture’ may lead to its distortion,” focusing particularly on orally transmitted culture.

As they interact with the tourists, cooking food, setting up camp, making tea or simply guiding them through the desert, the Bedouin explain aspects of their lives.

Tourists look for an exotic other, a romantic experience with the thrills of adventure as well as the mystery of the desert’s silence and open space. And the Bedouin become obliging hosts.

In a sense, tourists constitute the audience before whom the Bedouin acts out or performs a Bedouin identity. This is not simply about Bedouin hospitality, then.

But nor is it so simple as the guide making the consumer happy and matching the image of the Bedouin propagated by the tourist industry. With dramatic changes over the past century, Donald Cole, previously at the American University in Cairo, argues that ‘Bedouin’ now denotes less a way of life than an identity marker.

And perhaps what they present is not the same to everyone. Perhaps guides adjust their presentations of themselves according to who is in front of them. Indeed, our guide had very different ideas of foreign tourists and Egyptian tourists, suggesting that Egyptians did not fully appreciate the beauty of the desert.

The guides are all good cooks. Our guide, unlike some others we spoke to, said he would cook for his wife at home, because “the little girl keeps her up at night a lot, so it’s only fair.” But he had quite clear ideas about what women should and shouldn’t do — Bedouin women, that is.

When it comes to tourists, though, he seems not to mind anything.

“Who am I to judge?” he says. “They have come here to relax.”

While he did concede that he finds some of what he sees from tourists objectionable — and at odds with the ‘Bedouin identity’ he presented — his approach is perhaps an attempt to make sense of contradiction, a way to reconcile his identity as a Bedouin as he understands it, while also deriving meaning and even enjoyment from his work.

He was full of philosophical reflections, beginning many sentences with “Human beings are …” Some seemed rooted in lives related to the desert, such as “water does not go from the more thirsty to the others first,” or “he who is thirsty drinks first.”

For those who might think the Bedouin frame of reference is somehow widely different from peasant or urban Egypt, at times, his use of sayings was quintessentially Egyptian — such as “Al-haraka baraka,” or “Movement is a blessing.”

Anxious getting on a camel — my first time in over 15 years, I think — I ask the guide her name. He smirks.

“Halima,” he says.

He does not name the camels, they don’t have names. But if I am going to ride this thing without being scared, she is called Halima — a fiction of the touristic encounter that I am only too happy to indulge.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent’s weekly print edition.