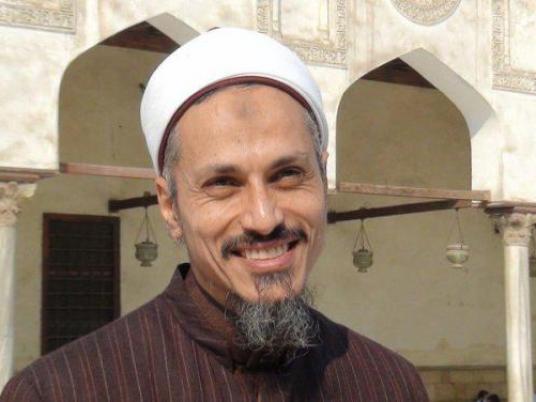

In commemoration of Sheikh Emad Effat's death one year ago, today, in the midst of the violent clashes near the Cabinet building, Egypt Independent reposts an article which was originally published on Mondoweiss.

A sadness, but not like death

When Emad Effat was martyred on Friday, 16 December, just before the call for sunset prayer, something began inside me that felt like death, or like the mourning for death. I didn’t think how strange it was then, nor about what it was exactly, because, after all, a man was shot, his face had become a mask, and his body was rocking on a sea of protesters like something left behind, and I had briefly, so briefly, known him.

Nor did I think it strange when I began to put my clothes on and to tell my wife, in a voice with something wrong with it, “I am going to Tahrir. If you feel you have to come with me, get dressed.”

Later, it was clearer that I had begun to see the strangeness of it when Tarek, who knew him better than me, had called, minutes after I found out, and said, “They killed him, Waleed, they killed Sheikh Emad,” and I consoled him as best I could. But at the time, it seemed only to become apparent when we finally found out where the body was and walked past the small battle on Qasr al-Aini to the hospital and through that to that quiet clearing, surrounded by that little fence, and the sad yellow lights that light downtown, where another kind of battle was raging.

The figure of a sheikh in robes and turban, head and shoulders taller than a crowd of men and women all raising their voices asking him for something, begging him, with a keen, howling sadness that seemed to tear itself from inside them. And the sheikh, whom I knew, begging them to understand that he could not give it.

As we walked toward him, he pulled away from them as though wounded and rounded a corner. We followed him and found him standing alone.

I took his hand and looked him in the eye to remind him that I knew him, a little, and saw that same keen, howling cry trying to rip itself out of him that was still filling the air from the crowd a few feet away. I knew then that I was wrong to come, that this was not my place, and that is why I used those words of condolence, which held infinite meaning in the fewest words. I covered his hand with both of mine and said, “Only God remains.”

I spent some nights in Tahrir after that, because I knew now that what I felt for Sheikh Emad and his death was not mourning, but that it shared with the mourning for death some things, and that one of those things was sadness, and I wanted to know if it was a sadness for death, or maybe something like death. I would walk along the river and turn right, and there, at the end of the road, was the wall they had built, primitive, clumsy and huge, as though to mark the end of the world, and behind it nothing but the blinding cold light of the military spotlights, as if behind it lay nothing but heaven or hell or that light they say the dying see.

As I walked toward the wall, people stood gathered here and there, almost for warmth, around some figure speaking. One of them cried out, “These martyrs — these matryrs whose blood is on the ground — are they any better than us?” And the people in the crowd would shake their heads and say, "no." And I thought, surely that can’t be right. Surely dying is the calamity, and we were privileged to live: we who felt, or did not feel, that howling cry of mourning, and they who left blood behind, for us.

But then, as I sat on the ground and leaned my back against the wall, I thought of that man with the mustache, and the blood on his shirt, who told me last February, for no reason I could see, and with a look of grief in his eye, “This blood is not mine. It belongs to the guy who was standing behind me. The officer holding the rifle was on the street below me, and I was on the bridge. I saw him just as he raised the rifle and I stepped out of the way. The bullet hit him right in the chest. I turned to pick him up, to help him, but he was dead, you see?” I nodded, because I did see, but then the man relaxed as though he had been anxious that I wouldn’t see at all, and with that easing up, he presented me with the real thing he wanted to say about that man who got shot. “Lucky bastard,” he said. “Must just have been a better man than me.” And something other than mourning had come into his eye.

I knew what he meant of course, but I had a bitter thought then. Maybe he’s right, I thought, and gathered my coat around me in the cold. The sadness was for death, and the dying felt that, and their families and their friends. And perhaps that other thing, that other thing that came into his eye, was only a thing that the living felt, when others died and not themselves. And I would have sat there, thinking bitter thoughts in the cold at the bottom of the wall had it not been for that story that Mahmoud Samy of the April 6 Youth Movement had told us. Before telling the story, Mahmoud said to Moataz and me that it was God who chose martyrs, and that He would never pick one of us. “Why?” We asked him. “Because,” he answered, “we’re sons of bitches.”

And then he told us the story of that boy he was standing next to, on the same bridge, on a different night, when after the Battle of the Camel, and near dawn, he had joined those who slipped past the barricade the protesters had set up. They had attacked the bridge from which the police and thugs were firing. “He was two centimeters in front of me and to the side, and then a wound appeared in his back, near his kidney. There was no sound, it just appeared, and then he cried out as he was running, and fell. We picked him up, me and another man, to carry him to the field hospital. He died before we got there. On the way, when I looked down at him he was smiling. The man who was carrying him with me yelled out to clear the way, 'Out of the way, boys! A martyr is coming!' I yelled at him to be quiet, and looked down at the boy we were carrying to see if he had heard. He was laughing.”

There was a silence after he told that story. And now, at the bottom of the wall, there was another silence, and it was filled with Sheikh Emad. I remembered his wife on television, saying, “When Emad went on pilgrimage this year, he asked for martyrdom, and when I asked him about it he said, ‘God willing, it will be this year, and in Tahrir.’” No, I thought. Those who go, go their own way, laughing. On this side, at the foot of the wall, lie the mourning and its sadness, and that other sadness that isn’t tied to mourning but may be tied to death, all that exists for us.

Nor did I find out that night if it was tied only to death, but the next night I saw a child, homeless, perhaps 11 years old, in torn clothing, barefoot and filthy, sitting on the shoulders of a man, chanting slogans and throwing his fists in the air. He was shouting at Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi that he wasn't afraid, and then, because he was shouting as hard as he could, his voice broke, and he faltered and then he was yelling in a broken voice with all the strength left in his birdlike body, his voice no louder than a whisper until I wanted to beg him to stop. I felt something in me soften, sadden, and with the saddening I wanted to cover him with my coat. And the thing inside me I had for Sheikh Emad was there, and the same sadness that came with it, and which I now knew I had for that little boy also. It grew until I walked to the pavement and sat down.

Later, when he was sitting on the same pavement with his head bowed, I walked up to him. My shadow covered his body, and he looked up at me towering above him. “What the hell are you doing here?” I asked him. He answered, his voice still a hoarse whisper, “I want Tantawi to go away.” “Why?” I said. He sounded tired, and he said in a tired monotone, “Because he is unjust and the people are being exploited, and the revolution was triggered the middle classes but is only going to be continued by people of the lower classes like us.” I pressed my lips together to keep from laughing. I even managed to keep myself from asking which political movement had taught him those words. It didn’t matter anyway, there were many of these movements in the square, and many boys who felt they understood more than the others. What mattered was now, when I thought of Sheikh Emad, as when I looked at that little frail bird of a boy, the sadness that came to me came with a smile.

Nearer to dawn, I met another little boy, sitting on the fence. He came to listen to us talk around the fire. I was tired and I had a pain in my back. I was asking the men around me when the hell the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces was going to leave so I could go lie down. The boy was watching me, chubby, barefoot and dirty; he was knocking with a stick against the fence he was sitting on, over the fire. Halfway through my rant, he tilted his chin toward me and spoke. “Hey,” he said. I stopped. “Yes?” I said. “You want the council to leave?” I said I did. “Wait,” he told me. We all waited, but he looked at us, with total confidence, and continued to tap his stick against the fence. After a while, I said, “Wait?” “Yeah,” the boy told me, “Wait. Make a decision and then wait. Wait long enough and one day you’ll turn around and find them gone.” A long moment passed. I turned around to the man standing next to me. “This boy is a political prodigy,” I said and the man smiled. The boy nodded regally in acknowledgment. Then a thing happened that brought back the sadness of Sheikh Emad.

“I … I just have a question,” the boy said in a low voice. He pressed his lips together like the small boy that he was, and looked down at his feet. “What exactly is the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces?” As the laughter started, I smiled and softened for the third time that night. When the laughter died down, I took a step toward him. “It’s like this,” I started. As I explained to him, as best I could, what SCAF was, and why it needs to go. I thought about what one of Sheikh Emad’s relatives said when asked why Sheikh Emad was in the square: “He was there because he couldn’t bear to see anyone suffer.” I think that what’s inside me right now for this boy. It is what was inside Sheikh Emad until the moment he died, and this is what’s inside me also for Sheikh Emad. But I don’t know. What I do know is this: that it is a sadness, but not like death.

A fierceness, not quite like battle

The bullet entered sheikh Emad's body on that Friday in December, just before the caller called for the sunset prayer, through his left side. It made an entry wound, passed through the lungs, and then exited through the right side of his body, making an exit wound. The bullet passed right through the body, not settling, indicative that it was shot at close range. Lacerated blood vessels leading to a sudden drop in blood circulation and death. Sheikh Emad was not taking part in the sit in in front of the Cabinet building, he was simply passing through by accident. The bullet, entered sheikh Emad's body through the right side, made an entry wound, passed through the lungs, entered the heart, passed through the heart, killing him instantly. It then passed through the left side of the body, causing an exit wound. The trajectory of the bullet was straight, with no curvature: he was shot at close range. Sheikh Emad was, in fact, present at the sit in, but only to urge the protestors to go home. The bullet was shot from a distance. The first report is denied by the same official government body that made it. The bullet wound that killed sheikh Emad Effat lacerated his liver and kidney. Sheikh Emad Effat, in charge of the written fatwa-issuing section at the government's Dar il-Ifta Department, affiliated with the Department of Justice, was at the sit in, and did not tell the protestors to leave, but was only there to calm everyone down and encourage them to be more reasonable. The bullet, entered sheikh Emad's body through the right side, made an entry wound, passed through the lungs, entered the heart, passed through the heart. But it was shot from a distance, possibly from a rooftop. It killed him instantly.

When sheikh Emad was martyred that strange thing that began inside me, while sad, was also fierce like battle. At the clearing in front of the morgue a battle cry was raised, also, “Let us tell people the truth!” And the sheikh from Dar il-Ifta, who I knew a little, raised his hands as though calling for a truce and tried to answer each question as it came, and, finally, pulled away and walked around the corner. “Its sheikh Emad's family and friends,” a friend of mine told me. “Dar il-Ifta issued a formal statement. These people want it corrected. And they want it known who shot him. The sheikhs said they would wait for the forensic report. We told them it would be fabricated.” He shrugged. A sort of rhythm began in my chest, something fierce and relentless. I recognized it because it had become so familiar over the past year, and it beat and beat, all through that night and into the next day at the mosque when the dignified employee of Dar il-Iftaa took up his dignified microphone and said in his dignified voice that “We don't know, you or I, who is, in fact, the murderer of sheikh Emad…” and was cut off by ten thousand lions roaring, hurt and angry. And then the afternoon when they wouldn't let us take him to Tahrir, where he would have wanted to go, and the next night, when after we took his body to be covered with earth, we walked and we walked and we went to Tahrir for him, and when we arrived at the wall that was being built in Tahrir, and all through the battle which raged at the foot of it.

It kept on beating as we came to the road, and saw the wall at the end of it, and the fire raging behind it and the shouts, and for a moment it seemed the beating was inside me and that even so, it came from in front of me and I was walking toward it. I stood still as the thousands shouting out for sheikh Emad walked by me, because I knew what I would find at the wall. Fire and smoke, a rain of rock, a trembling at first and then that fierceness, and all the time a beating, like a second heartbeat of rock and metal all around us, and we would be free, and yet. And yet.

I tried to remember what it was for, this beating and the fierceness, and I did it for sheikh Emad, because I knew now when I saw that wall that it wasn't when he was shot on that street. That it was for him also, the beating and the fierceness but that it didn't start with him or end with him, but only went through him. I thought at first that it may have been a fierceness for battle, but I looked at the fight and felt a kind of patience, a longness of the spirit that had nothing to do with that kind of battle. I almost lost the thread when I woke up the next morning and found that they had gone into the square, after I had left, just after I had left, and the numbers had dwindled and they killed who they could in the dark, and beat others and stripped women on the street and tore at their flesh like hyenas in uniform. The fierceness rose, relentless and hard, and for some nights after that I arrived at the square in the still of the night, and waited for them till dawn.

There in the middle of the night, I thought of sheikh Emad. I knew, from one of his students, that he had been here, right here on this ground, since last January. That he took care of his family, went to work at Dar il-Ifta, and that he would then take of the robe and turban. In his tracksuit, he would come to Tahrir, as though he were not a teacher of men, and sit and sleep on the ground like the rest of us. Some of his students said they saw him sweeping garbage off the sidewalk. And he would stand before the bullets, the rocks and the fire when he had to, if it came to that. He had done it, in the end.

I thought about them going to work in the morning. Major General Mansour al-Essawy. We do not under any circumstances move against anyone except if they try to break into the ministry building: violence is unacceptable. Major General Abdel Moneim Kato. International law permits armed forces to respond to attacks against it by protesters. Major General Adel Emara. Our soldiers were protecting embassies and gas stations. They are armed with a stick, not bullets, not gas, nothing of the sort. Lieutenant General Reda Hafez. The Egyptian army has not, and will not, ever, fire a single bullet at the Egyptian people. Field Marshall Hussein Tantawy. The widely promulgated videos of the girl in the blue brassiere were falsified. The soldiers were actually helping the woman reclothe herself. She was wearing provocative clothing.

"Emad,” the sheikh's wife said in an interview on television, “Always told the truth. If he said assalamu alaykum, peace be upon you, to you, in greeting, then it was a prayer. A prayer for peace.” Among the last conversations that he was to have, perhaps two weeks before his death, was one overheard by Tarek as he sat in the sheikhs office at Dar il-Ifta.

A man called asking for a fatwa, a non-binding legal opinion from sheikh Emad, Tarek told me. He wanted to know if it was permissible according to the Sharia, for a police officer or other government official to fire upon protesters. “No,” said sheikh Emad. “And if they are attacking the police with rocks?” The man asked. “No.” “And if they are destroying property and causing damage?” “No.” “What if they are causing civil strife among them Muslims,” the man said, invoking the most grievous of social acts in the religion. “No.” “Is there any circumstance where perhaps a police officer is entitled to shoot at a civilian?” “In theory,” sheikh Emad said to the man, “It is possible that there is a circumstance where an officer may shoot a civilian, non-lethally, but I, for one, will give no such opinion.” There was something about the no of sheikh Emad that was, like this thing inside me, fierce. And yet, although his no did not explain it, there was something in it of that relentlessness, that patience and that longness of spirit that I sensed as I watched that last battle at the foot of the wall.

I could not in the nights I was in Tahrir thinking about him, understand what this thing was inside me which was in part sad, and in part fierce and patient all at once. I did not understand because you see, if it was fierce, then how could it not be like battle?

I was answered by a man who came to stand next to us and warm himself by the fire, and who was, may he forgive me, the most ugly man that I had seen in many years. Tall but with a hunched back that made him slightly shorter than me, with a wide mouth with almost no teeth in it, thin and bent, with muscles which were grotesquely strong in some places and atrophied in others. He snorted when he spoke, and laughed and swore as he told us about how he had spent the last couple of weeks in a strange monologue with no breaks in it.

"The birdshot was weak when it hit me cause of my trousers but that whore-son rubber bullet shit they use marked my body up all over haha hahaha hoooooo boy I took me some of that rubber from here and then I said its all over thank you for the show boys I said I swear by my mothers tit I would never try to conquer Jerusalem again I swear to God brother sons of bitches treacherous sons of bitches you talk to them hey! why don't you shoot them over there with that stuff you got there why the hell are you shooting at me I'm just trying to talk some sense into all of you and then when it's all over and what happened happened you hold up your hands for truce snort snort you wanna drive us out of our fucking minds or what yelling peaceful! peaceful! so what're you going to do we went in to talk to them well boys they say forgive us will you we have orders you know how it is and then when the trouble starts again they punch snort hahahaha I swear to God cousin they punch you full of holes enough already you whore-son bastards hahaha four times is more than enough for me thanks. Treacherous fucking bastards. It won't do man won't you see some sense it can't be that you're my cousin and maybe my brother and then when we've talked and we're all alright now and we say hey why don't we go somewhere and all that and then you haha snort fuck me up with that rifle cause some kids came in and threw some rocks you shoot me with that rifle and i'm running running running and tripping over myself and each other like we're playing video games jumping over doors and whathaveyou like monkeys they don't know who who's coming and who's going bam! bam! bam! and that poor sheikh coming to keep the peace and three dead just three how can that be out of all these thousands fighting where's the justice where's the justice where's the justice God dammit and why would we want to burn the place if we did it would be smoke and ashes no and those heathen cocksuckers with that girl with the bra you know she's a doctor didn't you know they said a blue bra fuck me what does it matter for fucks sake ha ha snort ha what colour bra she's wearing?”

And right there, hands out over the fire and crying with laughter, seeing this ugly man with the obscene tongue which made me flinch, who was utterly lacking in manners and filled with a strange, grotesque innocence I had a fierce and generous and patient thing inside me. I thought, as I wiped the tear from my eye, of sheikh Emad sitting on this ground, as a teacher of men, clearing the garbage for them off the side of the street. And I thought, as I tried to catch my breath, it's a fierceness alright, this thing you feel for him, or through him. And then, as I looked at the graceful monster standing next to me and laughed again, I thought: its a fierceness, but not quite like battle.

And consumes one, like life itself

After the bullet had passed through the body of sheikh Emad Effat, his body hit the ground, and his spirit rose to meet its Lord. A short while after that the caller called for the sunset prayer, and night fell on a Friday in December. His family and friends, his teachers, his students, and many others who did not know him mourned him. Them and others felt towards him something else also which wasn't mourning but which shared with mourning something sad and something fierce, and something else which I didn't yet know, and I was one of those. All this is beyond dispute.

And yet, that night, in the tiny clearing in front of the morgue, under the sad yellow lights, there was a dispute. His family and friends, among them a woman wearing a scarf on her head who if I remember correctly was his wife, wanted Dar il-Ifta to tell the world how he was shot, and who it was who was standing next to him, and carried him, whose hands were drowned in his blood, and who tried to save him. Above all, they wanted them to say where he was when he was shot, and why. Why he was there, and why he was shot.

The sheikh they were disputing, who is called sheikh Amr Alwardani, and who was sheikh Emad's faithful friend, repeated again and again, that he is gone, and that “We do not want people to buy and sell him in the markets of this thing.” The sheikh who had been there earlier, and who had taught them both, and who loved them both like his own children, and whose name is sheikh Ali Gomaa and who is the Grand Mufti at Dar il-Ifta, had responded by saying, “We take only the facts. We will wait until the forensic report reveals the facts about his killing.” Something is wrong here, I thought, and a kind of anxiety began to rise in me. They are missing something. I've heard this kind of talk before, I thought, and as I thought that I knew that the anxiety came because those words are a veil, and behind them, there was something at stake which those words covered.

I called Nuri, a student of all three of those sheikhs, the one who was gone, the one who was his friend, and the one who was his teacher. It was an international call. “Help me, Nuri,” I said, over that distance, “Help me. I don't understand, what are they doing?” But Nuri didn't know and, calm from the distance he said, “And it seems to me, you also, don't know what you want them to do.” The next day, when sheikh Emad's wife suggested that we pray over his body in Tahrir, and then go to bury him, sheikh Ali refused. She asked why. “Azhar is a symbol,” he said. “Let us maintain the symbol.”

For the next three days, at around 3:30 in the morning, the army would switch off the lights in Tahrir square, and, using soldiers on the ground and snipers on the roofs, sticks and sidearms, fists and feet, beat, imprisoned and tortured and killed untold numbers in an effort to clear the square. At dawn, they instantly retreated. This is indisputable. At the end of those three days, while we sat in Tahrir all night, hoping numbers would protect those camped out there, Major General Adel Emara gave a press conference.

It contained, among other things, an impressive list of facts. That girl with the blue bra, was covered in the end by a soldier. That soldier was struck by a rock. The incident is under investigation. The building burned during the events contained rare books, among them the Description of Egypt made during the French expedition. Civilized countries have independent judiciaries. The Description of Egypt is a very important book. The army did move in on protesters, in order to build a wall. The wall separates soldiers from protesters. It's good to be reasonable. The building where the Description of Egypt was kept is a very important building. There are many street children, poor people, and people who have taken drugs in Tahrir. Do you realise just how important the Description of Egypt is? These street children who are poor and on drugs, occasionally raise their hands in the victory sign. Sometimes this is in front of buildings containing rare books. Countries without history, and nations without memory, if both were, say, burned in a building containing rare books, are nothing. The soldiers in the army are the soldiers of this country. Those soldiers are your brothers. Revolution. Order. Stability. Elections. Democracy. Egypt. Egypt. Egypt.

"What we are seeing, boys,” Motaz said as we watched this conference, “is the failure of language.”

But what I was also seeing was two flags on one side of of Major General Emara, two on the other, and above him a large icon of an eagle, drawn in abstract lines. It wasn't any particular eagle, you understand. And that was when I thought about the last thing I had inside me for sheikh Emad.

I had met sheikh Emad, once, and seen him several times in the Dar il-Ifta when I worked there four or five years ago. I used to pray on the second floor where the open praying space was surrounded by the offices of the bureaucracy of the place. Sheikh Emad sometimes walked by, tall and slim, and with the kind of severe elegance that only integrity can give he would stride up the stairs. The pictures of him now all over the Internet are almost always of him smiling and almost fragile, but that is what I remember, except perhaps the one time I think I remember him speaking to sheikh Amr Alwardani. Then he was filled with a delicate grace, and a gentleness, and, of all things, precise, almost aristocratic, diction. And that is all.

I have since then, however, found out other things, from people he held him much closer to his heart, and who held him to theirs. His wife corrected the interviewer: Do not make the mistake of letting the sombre nature of the robe and turban fool you, she told her. “Emad was,” she faltered, searched for the word, shook her head, “sometimes he would just, for no reason, send you an Umm Kulthum song… when he saw something he liked, he would let loose a loud whistle,” she said, smiling. I understood. A female student of his, Najah Nadi, living now in the States, wrote how he kept a bag of sweets, from which he would occasionally throw one to his students, grown ups all, when they answered a question correctly. In an earlier letter, she wrote him a letter after she heard the news. She rebukes him for being the cause of the loss of his own presence, “And you, O sheikh, why would you ask God for martyrdom, knowing full well that He would answer you?” Yes. Why would such a man, make such a request.

"He never asked my opinion on going down to the square,” said the Grand Mufti, “He blamed me for not going there myself. He would say of it: 'the air around Tahrir now, is purer to me than the air around the Kaaba.' I criticized him for the statement.” And who knows, perhaps the martyr was wrong on this one, or perhaps he has the reward for that opinion. Yet he saw something there. And he saw it before all of us. Nadi's letter tells how he would send them email after email since she became his student years ago, filled with nothing but concern for the murder of the muslims in lands other than his own, in Afghanistan and Iraq and Palestine. About this latter one of his students said it was the subject of most of his emails. Ibrahim al-Houdaiby once tweeted about the massacre of the Copts in Maspero, that any talk which does not begin with the condemnation of this crime of murder, through bullets, tanks and media, is talk which is an affront to humanity and patriotism. Sheikh Emad, who tweeted nine times in his life, added, “And to religion.”

What he saw there consumed him, and moved him to speak and to act. When the time for elections came, he declared, without fear of blame, his opinion that to vote for ex-members of the regime is a sin outright, as it is to vote for anyone who has been proven to be corrupt, whether from the past regime or not. He stood before the bullets and the rest of it. And something about what he saw, before and after had about that which was so lucid it drew aside the veils. El-Houdaiby said to a journalist once, “He assured me that the travel ban that the regime had put on me would be lifted soon, and when I wondered how this could happen, he said Mubarak won’t last until April 2011.” And after the events. He would strip off his turban and robe, and free of that symbol, he said to everyone he met, as though veils were drawn aside, that he could smell coming, from the direction of Tahrir, the scent of Paradise. For all of them, God willing. But for his loved ones there is only a little mourning, and that other thing which we can share with them, which is not like mourning: sad, but not like death, with a fierceness not quite like battle, and which consumes us, like life itself.

Waleed Almusharaf is a PhD student at the School of Oriental and African Studies.