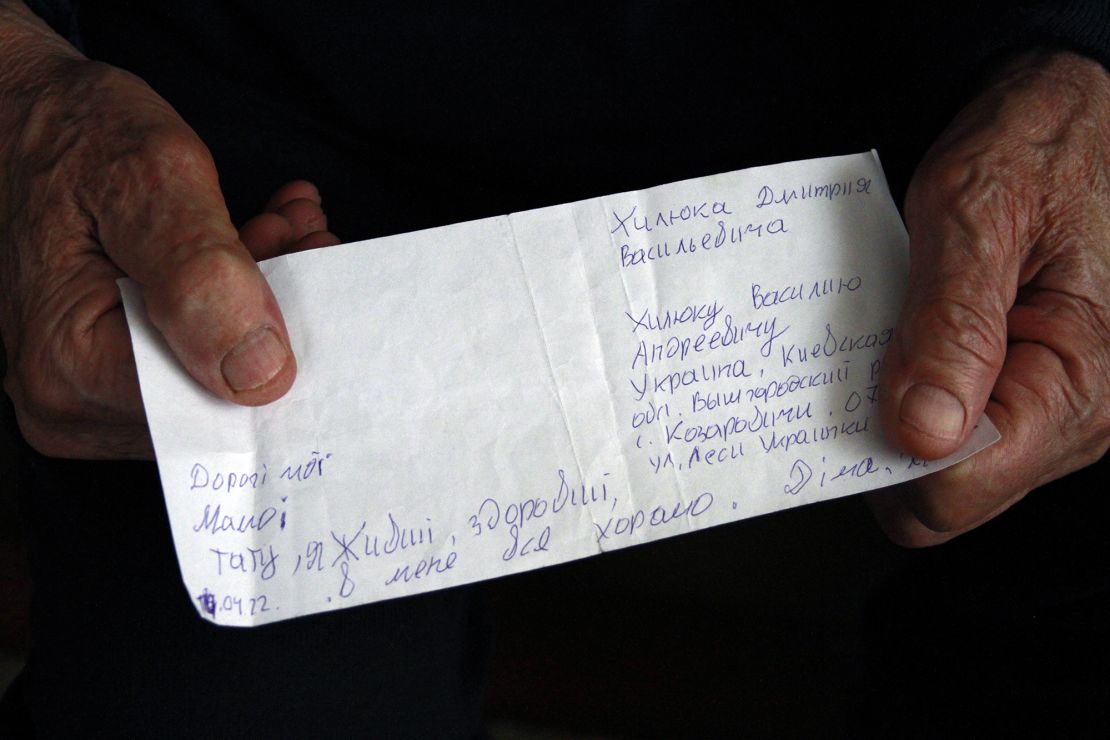

“Dear mom and dad, I am alive and well. I am doing well. Dima.”

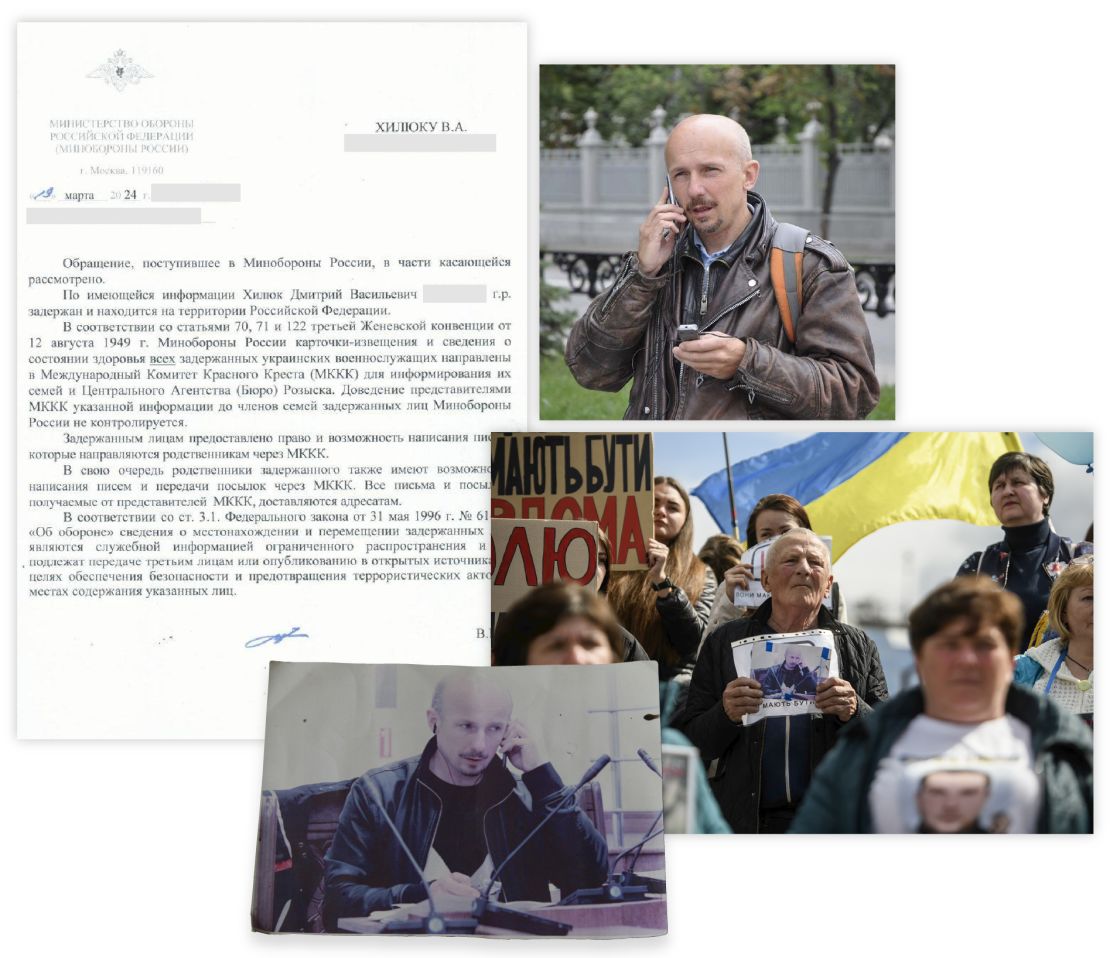

Handwritten on a small piece of paper, this is the only message Halyna and Vasyl Khyliuk have received from their son Dmytro Khyliuk, known as Dima, since he was taken by Russian troops more than two years ago.

The Ukrainian journalist was detained in March 2022 during the occupation of his village, Kozarovychi, north of Kyiv. As far as his parents know, the 49-year-old correspondent for the Ukrainian Independent Information Agency was transferred to Russia, where he is still being held despite – according to his lawyer – having never been convicted or charged.

The Ukrainian government says there are thousands of people like Dima, civilians arrested by Russia who have been held in arbitrary detention for years. Kyiv has officially confirmed around 1,700 cases, but human rights researchers estimate the real number is five to seven times higher. In all, some 37,000 Ukrainians – civilian adults and children, and military members – are unaccounted for, according to the Ukrainian ombudsman’s office, which says that people are still being seized in areas under Russian occupation. CNN cannot independently verify the number of detainees.

Many of those detained have been moved to prisons deep inside Russia, kept alongside criminals and prisoners of war, in breach of international humanitarian law. Human rights groups have identified some 100 detention facilities across Russia and occupied areas of Ukraine where civilians are being held, including several that have been opened or expanded specifically to accommodate them.

“The Russians want to recognize a lot of them as military combatants and give them prisoner of war status … the main reason being (to build) a bank of POWs for exchanges,” Ukraine’s human rights commissioner, Dmytro Lubinets, told CNN in Kyiv. Lubinets said that recognizing Ukrainian civilians as prisoners of war would be both illegal and dangerous, because it would put Ukrainians in occupied areas at higher risk of being detained to be used as bargaining chips.

“These people are not prisoners of war; they are civilian hostages. I use that word to emphasize what the Russian Federation is doing – they are holding civilians as hostages,” he said. Under the Geneva Conventions, that regulate the conduct of armed conflict, hostage-taking is explicitly banned. Warring parties can intern people, including civilians. But the rules on who can be detained, why and for how long are strict.

“The rule is that it is not a punishment,” Achille Després from the Kyiv branch of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) told CNN, adding that civilians can only be held if it’s “necessary” for “imperative reasons of security.”

The Ukrainian government and several international organizations say Russia is committing war crimes by holding people like Dima. Concerns over Russia’s arbitrary detentions of Ukrainian civilians are so grave that 45 members of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) launched a special investigation into the issue in February with the aim of finding ways to hold Russia accountable.

Desperate search

Speaking to CNN at their home in Kozarovychi, which has since been liberated and partially repaired by Ukrainian volunteers, the Khyliuks recalled the horror of their son’s capture and the uncertainty of his continued detention.

In the early weeks of the war, Russian troops took over their home, parking their tank in the garden and stealing anything of value. The Khyliuks were sheltering at a neighbor’s house, only occasionally venturing outside to get supplies. It was during one of these outings that Dima and Vasyl found themselves surrounded by a group of Russian soldiers armed with machine guns.

“They put some kind of jackets over our heads and taped our eyes, so we couldn’t see anything. Dima and I were separated. Then a week later, they took us to Dymer. We spent two nights there together. It was cold, the floor was cement, it was not heated. I was wearing a winter jacket, but Dima was wearing a light jacket and wellies,” Vasyl, who was released after eight days, said.

When they didn’t come home, Halyna said she was beside herself, realizing the Russians must have captured them. “They grabbed a lot of people back then, they grabbed whomever they saw. Those they did not need, they tortured a little and let them go. But Dima and six other people have been in prison for two years,” she said, tears in her eyes.

Russia has become such a black hole for information that many Ukrainian families, authorities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) must rely on word of mouth from former prisoners to learn about people who are still detained.

Anastasiia Pantielieieva, a researcher and journalist who documents cases of civilian detentions and enforced disappearances for the Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR), a Ukrainian NGO, said that, based on eyewitness testimonies, Dima was briefly held in two makeshift detention centers in occupied Ukraine before being moved to a pre-trial detention center in Novozybkov, in Russia’s Bryansk region.

She said the last documented sighting of Dima by a witness was at Penal Colony Number 7 in Russia’s Vladimir region. At one point, MIHR received indication that he might be transported to another facility in Mordovia, a Russian region southeast of Moscow, but Pantielieieva said Russian authorities did not confirm this information.

Moscow has repeatedly denied holding Dima, despite numerous accounts placing him in detention facilities in Russia. The Russian Investigative Committee and the Russian Prison Service in Bryansk both officially informed the Khyliuks’ lawyer in December 2022 and January 2023 that he was not in Russia and that they had no information about him.

Dima’s handwritten note was dated April 2022, although his parents did not receive it until August that year. Then in May 2023, the Khyliuks said the ICRC called them to confirm their son was alive. But it wasn’t until this March, two years after his arrest, that the Russian Ministry of Defense admitted Dima had been detained and was being held in Russia, in a letter to his parents. They did not provide any information on his location or status.

“We’ve had cases where even people who are put on trials, public trials, where we have seen photos from the courtroom, even in these cases, the relatives would have no official documents, nothing that would officially confirm that the people are on the territory of Russian Federation,” Pantielieieva said.

Under international humanitarian law, in times of conflict, the ICRC must be given regular access to detainees to verify they are being treated humanely and to reconnect them with their families. The person must also be told why they are being interned and be able to appeal the decision.

Ukrainian Defense Intelligence officials told CNN that they believe the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and the Russian National Guard are the primary drivers behind the arrests and detentions of Ukrainian civilians. Neither responded to CNN’s requests for comment.

CNN also made multiple requests to the Russian ministries of defense and interior, the Russian ombudsman’s office, the Directorate of Special Programs of the President of the Russian Federation and the Main Directorate of the General Staff (GRU) for information about the specific cases mentioned in this story. They have not replied.

Held secretly for months

For the families of detainees, trying to navigate Russia’s security apparatus is a part of their nightmare.

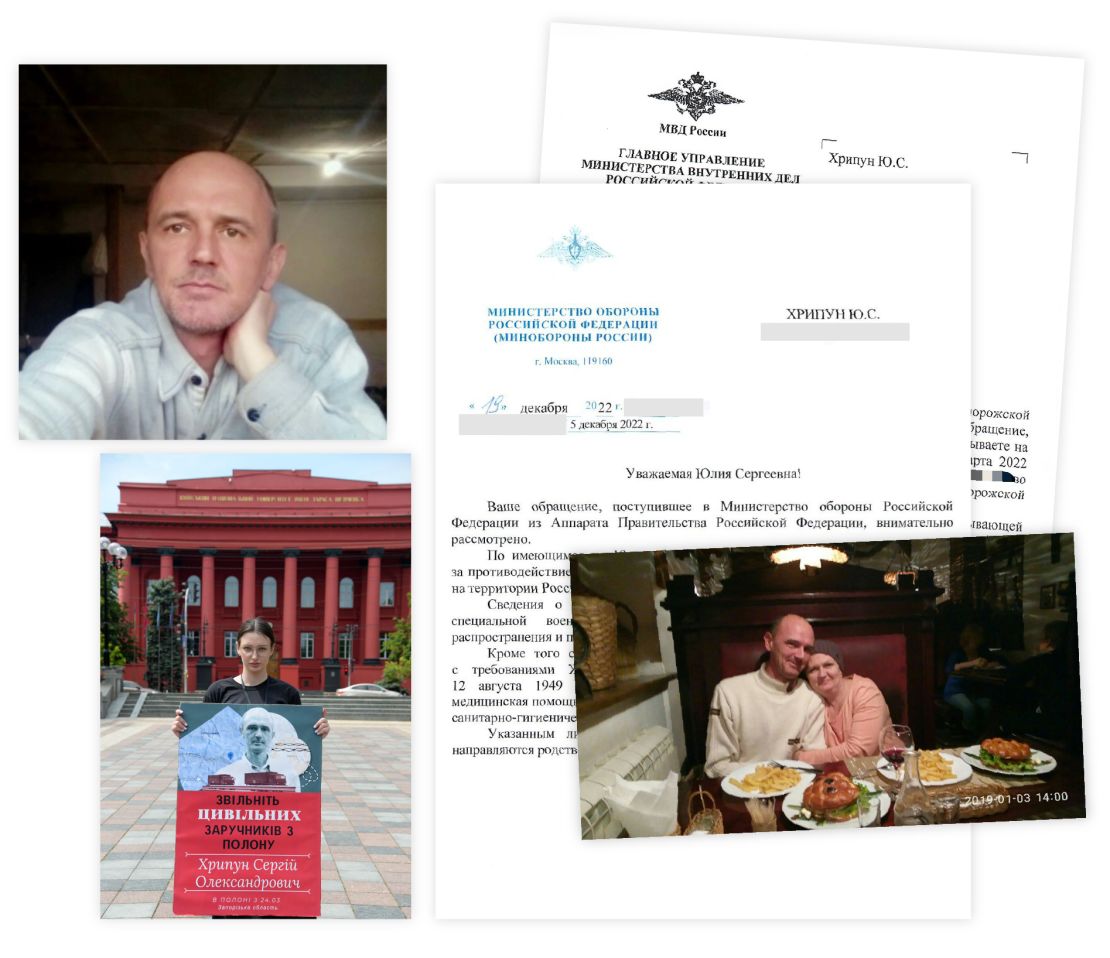

Yulia Khrypun has spent more than two years reaching out to every Russian authority she could think of, desperately trying to find information about her father Serhii. When she did receive official replies, they often included conflicting information. “One institution officially informed me that he was detained for resisting the ‘special military operation,’ while others said that he never crossed the border into Russia,” she said. CNN has seen some of the documents sent to her.

Serhii Khrypun was detained in Nove, a village near Tokmak, in southern Ukraine, where he was working as a security guard at a farm. The area had been under occupation for about two weeks when, one morning in March 2022, Serhii called Yulia to tell her that a new group of Russian soldiers had arrived in two trucks.

“And that was our last phone conversation. After that we had no information about him for two days,” she said. “It seems to me that at that moment he already knew that he would be taken away. He called everyone: me, his mother and sister, and his friend.”

Yulia was able to piece together what happened because Serhii’s arrest was filmed on a security camera at the farm; she said it looked a lot like kidnapping. When the Russian soldiers arrived, they searched him and his colleague before proceeding to undress them, the video showed. “After that, they put a bag over his head and took him away,” she said.

Yulia was told by Ukrainians taken to the same facility as her father – a government building in Tokmak – that he was held there for about two weeks. They also said they were beaten by Russian troops.

“He was then taken to Melitopol, where they kept him for three weeks, then to Olenivka, and from there to Kursk (in Russia), then to Crimea,” she said, citing what she has heard from various eyewitnesses who were held with her father. One of them contacted her after his release, knowing only her name and place of work from Serhii. Others were interviewed by NGOs or Ukrainian authorities. Based on these accounts, she believes her father is now being held in a detention facility in Kamensk-Shakhtinsky, a city in Russia’s Rostov region near the Ukrainian border.

Russia is holding so many Ukrainian detainees that it has had to extend several existing prisons and pre-trial detention facilities to accommodate them. According to the Ukrainian ombudsman’s office, one such facility has been created in Chonhar, at the Russian-occupied southernmost tip of the Kherson region, next to a bridge to the Russian-annexed Crimean Peninsula.

The FSB and other Russian security agencies have conducted a large-scale campaign of arrests and enforced disappearances in Crimea since Russia illegally annexed the peninsula in 2014, targeting political opponents, pro-Ukrainian and pro-democracy activists, human rights defenders, journalists and Crimean Tatars. Those detained include people with no links to opposition or activism.

The pre-trial detention center, or SIZO, in Simferopol, has become synonymous with the Russian campaign of terror in Crimea. According to Crimean human rights organizations including Zmina, the Crimean Human Rights Group and Crimea SOS, hundreds of people have been held in the facility for months, without anyone knowing where they were.

Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia opened a second pre-trial detention facility in Simferopol, SIZO No. 2. But that was apparently not enough to hold all detainees. Satellite images from Maxar Technologies taken in July 2021 and November 2023 reveal the transformation of a school campus in Chonhar from an ordinary building to a high-security detention center. A new security perimeter with high walls has been erected around the compound, with a controlled access point visible in the more recent images.

MIHR has compiled a database of facilities where Ukrainian civilians are being detained, confirmed through eyewitness testimonies from people held at the same locations and, in some cases, official documents. They include prisons, penal colonies and pre-trial detention centers as far away as Russia’s Irkutsk and Krasnoyarsk regions, thousands of miles from Ukraine in Siberia.

‘She was essentially kidnapped’

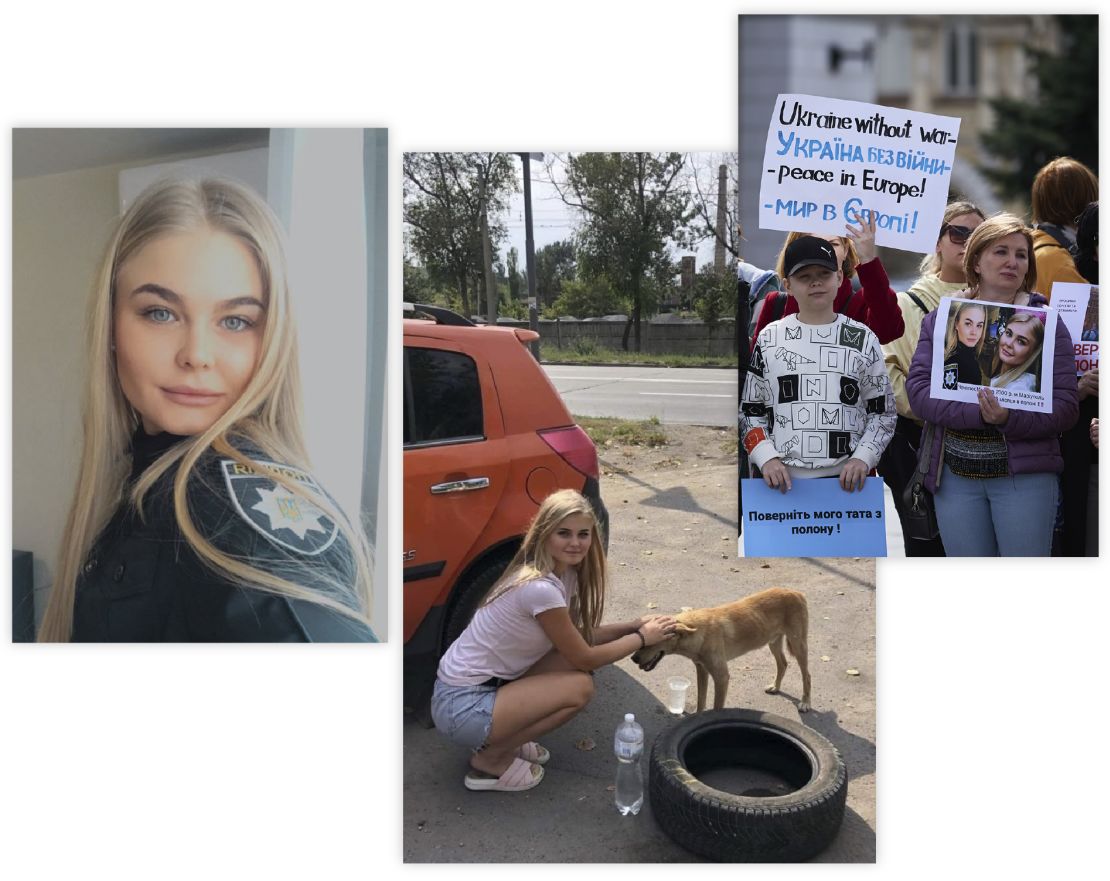

The family of former police officer Mariana Checheliuk has been trying to track the 24-year-old’s movements across Russia and occupied Ukraine for the past two years. Since her detention, she is believed to have been relocated at least six times.

Mariana and her younger sister were among the hundreds of civilians who spent weeks sheltering in the Azovstal steelworks plant in Mariupol during Russia’s siege of the southern port city. They were finally allowed to leave in May 2022, when Russia and Ukraine agreed to open a humanitarian corridor into the Ukrainian-held city of Zaporizhzhia.

On the way, Mariana was detained at a Russian “filtration point” in the occupied village of Bezimenne, according to her mother, Natalia Checheliuk. The Bezimenne facility became notorious in the early months of the war. Tens of thousands of evacuees from Mariupol were forced to go through a “security” screening there. Many never made it out.

“She was essentially kidnapped,” Natalia told CNN.

“There were no court hearings, she has not been charged with anything and we even received an email from the (self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic) prosecutor saying that they have absolutely no claims against Mariana, that she is not accused of anything and that they ‘will check and release her,’” Natalia said. “But this was eight months ago, and nothing has happened.”

According to eyewitnesses who were held alongside Mariana and who spoke to her family, she was first taken to a detention facility in Donetsk, in occupied eastern Ukraine. She was then transferred to Olenivka, the detention center where more than 50 prisoners of war died in a mysterious explosion in July 2022.

From Olenivka she was taken to a detention facility in Taganrog, in southwestern Russia, and then to Kamyshin, in Russia’s Volgograd region. From there, she was sent back to Taganrog and then to a detention facility in Mariupol, where – as far as the family knows, and as human rights groups and Ukrainian officials have reported – she remains to this day.

“My daughter went through a lot of grief,” Natalia said. “In a letter in December 2023, she wrote that she was giving up, that she had lost her faith … Every day, all day, all I think about is her.”

Before the war, Mariana – or Marianochka, as her family calls her – was an animal welfare volunteer, who would often get up early to prepare and deliver food for vulnerable dogs before heading to work with the police. She adopted a rescue dog called Mila, who is now staying with her family.

Eyewitnesses have told her family that the detention has taken a great toll on her. One Ukrainian woman who was held in the pre-trial detention center in Taganrog in May 2023 told CNN that Mariana had lost weight and was in poor health the last time she saw her.

She said Mariana had problems with her knee following an injury in Olenivka and that conditions in the prison were dire.

“The food was terrible, as was the attitude of the guards, who (inflicted) psychological and physical abuse on us. We were often forced to do push-ups, sit in splits, do squats and other physical exercises,” she said.

“Sometimes we could do physical exercises, sing Russian songs and the national anthem of the Russian Federation all day, (the guards) were threatening to send us to Siberia or other places … telling us that Ukraine no longer exists, that Ukraine does not want to take prisoners of war back, that no one wants us.”

The prisoner, who has since been released, asked CNN not to disclose her name for fear of retribution.

According to the ICRC, Russia considers Mariana to be a prisoner of war because she was formerly a police officer, Natalia said. However, the Ukrainian government told the family she is considered a civilian and, as such, cannot be exchanged.

Pantielieieva, the MIHR researcher, said she believes Russia would take advantage of any decision to recognize civilians as prisoners of war and detain even more. “The number of people they are taking is already great, they are doing it every day,” she said, adding that the latest case of a “disappeared” civilian had landed on her desk just a few days earlier.

Volunteers, journalists and teachers are among those Russia has appeared interested in detaining, according to the human rights groups monitoring the arrests, but often there is no discernable reason why someone has been scooped up. “Some people were taken because their house was not far from Russian positions. Or maybe they had a video of (Ukrainian President Volodymyr) Zelensky on their phones. Or the Russians were interested in their relatives and took them hostage,” Pantielieieva said.

“We have examples where a person is detained by one soldier and after a month, another soldier comes in on rotation and becomes responsible for the detainees and he doesn’t know why people were detained and he goes and asks the detainees why they were being held.”

‘I don’t know how to change this’

Ukraine has managed to bring hundreds of soldiers home in prisoner swaps with Russia and has even had some success repatriating Ukrainian children who were forcibly deported – leaning on Qatar and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to help mediate the process.

Detained civilians, however, are stuck in limbo. Only a few dozen have been released so far, Lubinets, Ukraine’s human rights commissioner, told CNN. “We don’t have a legal mechanism, we don’t have a partner, we don’t have international laws, international norms … I don’t know how to change this situation,” he said.

Ukraine’s government has admitted it was not prepared to handle the situation of civilians being held without end, but that they now have some systems in place to support families.

Yulia, whose father Serhii is still missing, said she realized early on that the international legal system was not set up to deal with cases like his.

“The process was clear with POWs, because for them there is a military unit, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) and Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters (for the Treatment of Prisoners of War). But with civilians, there were different phone numbers, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the hotline of the National Information Bureau, the ombudsman, the Ministry of Reintegration … it was a circle of hell,” she said.

After months of reaching dead-ends, Yulia and another relative of a Ukrainian detainee set up the civic organization “Civilians in Captivity” to give them more authority when speaking to officials. The group – which has united the families of some 400 detained civilians – has become a key player in raising awareness and holds regular meetings with the Coordination Headquarters and the ombudsman’s office.

“Everyone knows about the POWs, but few people talk about civilians in captivity,” Yulia said, adding that she sometimes feels frustrated about the Ukrainian government’s decision not to acknowledge civilian detainees as prisoners of war, as Russia has demanded.

“As a daughter who has been waiting for her father for two years, I do not understand why my father should pay with his life and health,” she said.

Lubinets said he understands that frustration. “But what can you do with (a) country that does not respect international humanitarian law and is not held responsible for it? The Geneva Conventions say that no side in international armed conflict can detain the civilian population. But Russia? They did it and they continue doing it.”

Video by Oleksii Markin and Boglarka Kosztolanyi. Graphics by Lou Robinson.