Mosab Abu Toha’s voice is smooth and melodic when he recites his poetry from his new home in New York. But when the Palestinian poet describes the people and the moments that inspired his writing, it turns raw with emotion.

“We are breathing on the outside, but inside, we are not,” he says.

Despite surviving physically, Abu Toha describes how the spirit to truly live has been shattered. Displaced from his homeland, where he worked as a teacher and librarian, he bears the scars of witnessing violence on an unfathomable scale.

“Our eyes are not seeing anything beautiful… We are not seeing the sunset as before. We are not seeing the sea.” For many in Gaza, as well as those who have fled, simple moments of beauty have been overshadowed by destruction and hopelessness from Israel’s war against Hamas, launched in response to the group’s October 7 attacks.

Abu Toha fled Gaza with his young family late last year, after relocating several times within the enclave. Eventually he was able to make it out because one of his children was born in the United States while he was doing a master’s degree at Syracuse University and therefore has US citizenship.

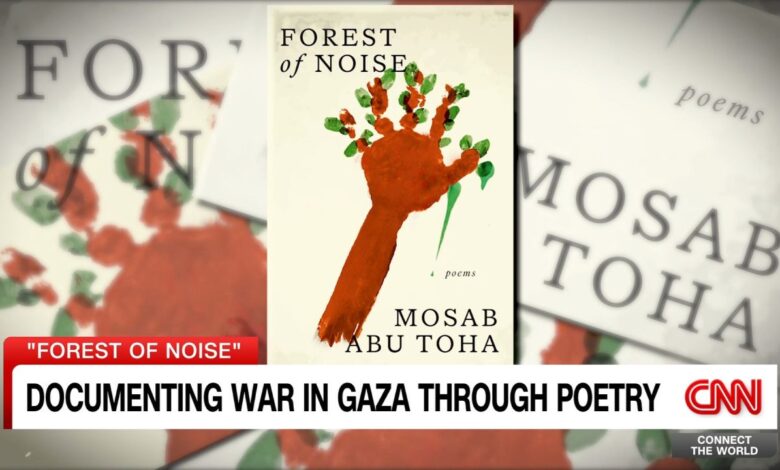

The journey out of Gaza was long and painful, but amid the chaos and devastation, he kept writing. Now, he’s releasing his second poetry book, “Forest of Noise,” written in English. In part, the book is an anthology of suffering. But it’s also about survival, he tells CNN’s Becky Anderson in an interview.

Living with the ever-present ‘buzzing’ of drones

“Each tiny foot hole in the street, each tiny bullet hole in the wall, is a forest of noise,” he explains. The air strikes, the rockets, the sirens of the ambulances are a constant presence in his memory. “I don’t remember living one day without hearing the drones buzzing.”

His debut book of poetry, “Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear” (2022) won the Palestine Book Award and an American Book Award. But for Abu Toha, the relevance of his most recent work lies not in his own story. “It’s not important that I wrote the book—what’s important are the stories of the people in it.”

Writing, though painful, is a necessary act of remembrance for him. “It is very devastating for me to write poetry, as much as it is devastating for me to read my poems to other people,” he admits. But sharing these stories is vital, even if the world seems unwilling to listen. “If this story does touch someone’s heart, then I’m doing my job as a human being.”

Abu Toha’s latest book revolves around this idea of survival, delving into the urgency of preserving the stories of those who have died while reflecting on his own existence as a survivor. “I know that their fate could be my fate. I survived an airstrike by chance in 2009 when I was 16 years old,” he recalls. “And I could have been killed in the airstrike that destroyed my house in Beit Lahiya.”

On October 28, 2023, Abu Toha’s family home, where he and over 20 relatives gathered after October 7, was bombed by Israel, he says. They had evacuated the house to Jabalya refugee camp a couple days before. “What if I was killed in my house with all my family? Would people come to my grave — if there was a grave — and say, ‘Oh, we are sorry about the mistake’?” His words reflect the constant fear of Palestinians in Gaza that any moment could be their last, lives hanging in the balance of Israeli military actions.

The struggle to explain the war to children

He struggles to explain the horrors happening back home to his children. “Even if they understand, it will not help them. What’s more important is for the world to understand this and do something practical about it.”

Abu Toha and his family found refuge in the US, but his disappointment with American policy is palpable. He recalls a moment when his child mistook clouds for the smoke of bombs Israel uses in Gaza. “He said, ‘Daddy, Daddy, be careful,’ and I looked. It was the clouds.”

Half of the poems in this second collection were written in the past year, the other half before October 7. “This in itself is a testimony that what has been going on since, has been going on for years,” he emphasizes, a reference to the deprivations suffered by people in Gaza under Israeli restrictions imposed long before the war.

For him, storytelling is not just a way of remembering, but a call to action. “If these people do not survive, at least their stories do.” His message is clear: The world cannot simply bear witness to these stories — it must act. The accounts of those trapped beneath the rubble, pregnant women struggling to survive, and orphaned children must reach those in power.

Abu Toha expresses frustration with the international community, especially the US, which continues to arm Israel. “Why couldn’t they stop the carnage in Gaza that’s affecting mostly the children?” he asks.

Abu Toha told CNN last week that he had lost 31 members of his extended family. “My family is still in mortal danger,” he said. Just three days later, he shared a photo of his 7-year-old cousin, Sama, who he says was killed in another air strike, along with a further 18 members of his extended family.

Sama was learning English. Every time she spoke to her older cousin, she would tell him all the new English vocabulary she had memorized since the last time they spoke.

Abu Toha’s parents and siblings still live in Gaza — one of whom is several months pregnant and was forced to relocate once again as Israel renewed its siege in the northern part of the enclave. “God forbid, if I, if I lose any one of my immediate family, I wouldn’t be able to bid them farewell. This is what it means to be from Gaza,” he says, with a voice filled with emotion.