The young woman rifles through a fridge of popsicles, pulling out several to show the camera.

“This is milk flavor – the picture is so cute,” she says in English, pointing to the cartoon packaging with a smile. “And this is peach flavor.”

After finally selecting an ice cream cone, she bites into it, declaring: “The biscuit is very delicious.”

The four-minute video has racked up more than 41,000 views on YouTube, but this is no ordinary vlog. The woman, who calls herself YuMi, lives in North Korea, perhaps the world’s most isolated and secretive nation.

Her YouTube channel, created last June, is one of several social media accounts that have popped up across the internet in the past year or two, in which North Korean residents claim to share their everyday lives.

But experts say not all is as it seems in these videos, and that the images contain tell-tale signs that the lives displayed are far from the norm for the impoverished millions under the dictatorship of leader Kim Jong Un.

Instead, they suggest, YuMi and others like are likely related to high-ranking officials and may be part of a propaganda campaign aimed at rebranding the country’s international image as a more relatable – even tourist-friendly – place than its constant talk about nuclear weapons might suggest.

YuMi’s videos “look like a well-prepared play” scripted by the North Korean government, said Park Seong-cheol, a researcher at the Database Centre for North Korean Human Rights.

Tell-tale signs

For decades, North Korea has been comparatively closed off from the rest of the world, with tight restrictions on free expression, free movement and access to information.

Its dismal human rights record has been criticized by the United Nations. Internet use is heavily restricted; even the privileged few who are allowed smartphones can only access a government-run, heavily censored intranet. Foreign materials like books and movies are banned, often with severe punishments for those caught with black market contraband.

This is why YuMi – who not only has access to a filming device but YouTube – is no ordinary North Korean, experts say.

“Connecting with the outside world is an impossible thing for a resident,” said Ha Seung-hee, a research professor of North Korea studies at Dongguk University.

YuMi is not the only North Korean YouTuber turning heads: an 11-year-old who calls herself Song A made her YouTube debut in April 2022 and has already gained more than 20,000 subscribers.

“My favorite book is ‘Harry Potter’ written by J. K. Rowling,” Song A claims in one video, holding up the first book of the series – particularly striking given North Korea’s typically strict rules forbidding foreign culture especially from Western nations.

The video shows Song A speaking in a British accent and sitting in what looks like an idyllic child’s bedroom complete with a globe, bookshelf, a stuffed animal, a framed photo and pink curtains.

Luxuries for ‘a special class’

The rosy depictions of daily life in Pyongyang may also give a clue to the social standing and identities of their creators.

YuMi’s videos show her visiting an amusement park and an interactive cinema show, fishing in a river, exercising in a well-equipped indoor gym, and visiting a limestone cave where young students wave the North Korean flag in the background.

Song A visits a packed water park, tours a science and technology exhibition center, and films her first day back at school.

Park, the expert, says these representations aren’t 100% false – but they are extremely misleading, and do not represent normal life.

There have been reports of North Korea’s wealthy elite, such as senior government officials and their families, having access to luxuries such as air conditioning, scooters and coffee. And the facilities shown in the YouTube videos do exist – but they’re not accessible to most people, and are only granted to “special people in a special class,” Park said.

These facilities are also likely not open or operating regularly as the videos imply, he said. “For example, the power supply in North Korea is not smooth enough to operate an amusement park, so I’ve heard that they would only operate it on the weekends or on a special day like when they film a video,” added Park.

North Korea is notorious for frequent blackouts and electricity shortages; only about 26% of the population has access to electricity, according to 2019 estimates from the CIA World Factbook. These blackouts were captured in nighttime satellite images in 2011 and 2014 that showed North Korea cloaked in darkness, almost blending into the dark sea around it – in sharp contrast to the dazzling lights of neighboring China and South Korea.

The YouTubers’ English fluency and access to rare luxuries suggest they are both highly educated and likely related to high-ranking officials, Park said.

Defectors have previously told CNN that some North Koreans learn British English in their English classes. The British Council, a UK-based organization, also ran an English language teacher training program in North Korea, sending teachers there for more than a dozen years before it was halted in 2017.

A new style of propaganda

North Korean propaganda isn’t new; previous campaigns have featured Soviet-style posters, videos of marching troops and missile tests, and images of Kim Jong Un on a white horse.

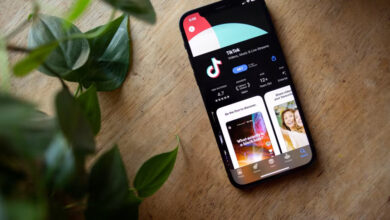

But experts say the YouTube videos, and similar North Korean social media accounts on Chinese platforms like Weibo and Bilibili, illustrate a new strategy: Relatability.

“North Korea is striving to emphasize that Pyongyang is an ‘ordinary city,’” Park said, adding that the leadership “is very interested in how the outside world views them.”

Ha, the research professor, said North Korea could be trying to portray itself as a “safe country” to encourage greater tourism for its battered economy – especially after the toll of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While it has not yet reopened its borders to tourists, “the pandemic is going to end at some point, and North Korea has been concentrating on tourism for economic purposes,” Ha said.

Before the pandemic, there were limited options for tours in which visitors were shepherded around the country by guides from the Ministry of Tourism. The tours were carefully choreographed, designed to show the country in its best light. Even so, many countries, including the United States, warn their citizens against visiting.

After the pandemic began, “there was talk (in North Korea) about shedding previous forms of propaganda and implementing new forms,” Ha said. “After Kim Jong Un ordered (authorities) to be more creative in their propaganda, vlog videos on YouTube began appearing.”

A 2019 article in North Korea’s state-owned newspaper Rodong Sinmun, citing Kim, declared that the country’s propaganda and news channels must “boldly discard the old framework of writing and editing with established conventions and conventional methods.”

The YouTubers’ use of English may reflect this effort to reach global viewers. Both YuMi and Song A also helpfully include English names for their channels: YuMi also goes by “Olivia Natasha,” and Song A by “Sally Parks.”

Why YouTube?

North Korea has posted other types of propaganda to YouTube in the past decade – though its official videos are often taken down by moderators.

In 2017, YouTube took down the state-run North Korean news channel Uriminzokkiri, and the Tonpomail channel controlled by ethnic Koreans in Japan loyal to Pyongyang, saying they violated the platform’s terms of services and community guidelines.

Another YouTube channel called Echo of Truth, purportedly run by a North Korean resident called Un A who filmed herself enjoying daily activities in Pyongyang, was taken down in late 2020.

But the closures sparked outcry from some researchers who said the videos provided a valuable insight into North Korea and its leadership, even if they were propaganda.

When CNN requested comment from YouTube on these deleted channels, and those of Song A and YuMi, a spokesperson said the platform “complies with all applicable sanctions and trade compliance laws – including with respect to content created and uploaded by restricted entities.”

“If we find that an account violates our Terms of Service or Community Guidelines, we disable it,” the statement said.

Experts said the videos by YuMi and Song A might be an attempt by Pyongyang to reach an audience without attracting the attention of moderators.

And however scripted they might be, they too offered a valuable window into the country, experts said.

“People already know that (the videos) were created for propaganda purposes … the public is already aware,” Ha said. But, she added, “I think there should be proper education and discussion on how we should perceive (such) content instead of just closing the doors.”