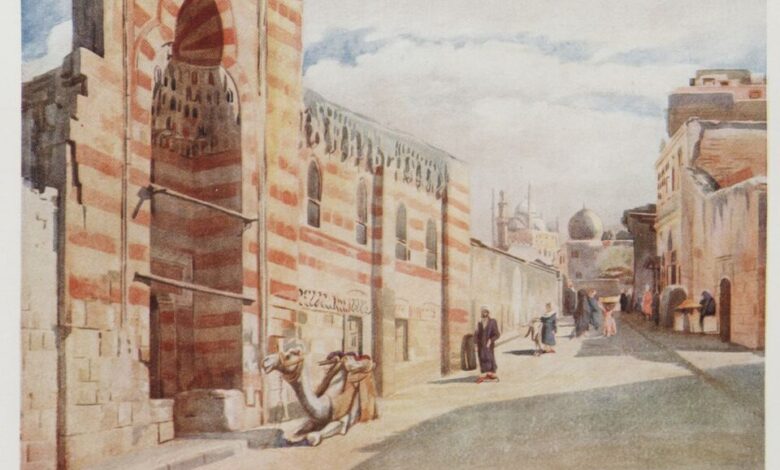

I have long been drawn to art because it can be a bridge between worlds.

After three years of studying Orientalism, working with an author to produce Orientalism Lives, and speaking with a wide range of experts, I have no doubt that not all Orientalist painters were the same.

There were the travelers—painters from the US and Europe who left behind comfort and familiarity to reach the Middle East. They journeyed under difficult, often dangerous conditions.

They learned local languages, studied Islam and regional history, absorbed traditions and taboos, and lived among Bedouins, Berbers, and other tribes.

They didn’t just observe—they participated, forging connections that spanned continents. In a sense, they were early globalists, building bridges between East and West long before the term existed.

Then there were the armchair Orientalists—painters who never left home. They created their “Middle East” from behind studio walls in Paris or London, using Western models, recycled props, and the public’s appetite for the exotic. These works were fantasy: marketable, but detached from the realities they claimed to depict.

The travelers had nothing to do with Edward Said’s critique in Orientalism. As someone close to Said himself confirmed, it is crucial to recognize that these were two entirely different schools.

Some of them went even further, taking moral stands for the people they had come to know. Étienne Dinet, for instance, publicly opposed France’s occupation of Algeria and supported Algerian independence—a position that cost him dearly.

Many others, though less famous, also spoke out.

Researching these artists has been one of the great pleasures of my life: following their journeys, reading their letters, tracing their sketches. Some left behind delicate handwriting that time has nearly erased—David Roberts’ script, for example, defeated my patience more than once.

But in every fragment, there is the same impulse: to understand, to document, to connect.

Perhaps that is why I have such reverence for these traveling Orientalists—they embody what art can be at its best: an act of crossing into someone else’s world with respect.

And perhaps that is why what I overheard at Sotheby’s the other day jarred me so deeply.

Last week I visited Sotheby’s on Bond Street in London. I’ve been going there for over thirty years and enjoy both their galleries and their knowledgeable staff.

Over time, I’ve developed friendships there and have always trusted their insight.

After walking through the galleries, I headed to their nearly empty cafeteria and took a corner table. I ordered a Darjeeling tea with a croissant, honey, and marmalade.

A few minutes later, three people entered—a woman in a flowery dress and high heels, and two men in suits and ties, one wearing a kippah. They sat at the table behind me. As my order arrived, I overheard them asking for two espressos, a bottle of sparkling water, a lemonade, a toasted cheese sandwich, and something kosher I didn’t quite catch.

Soon their conversation grew quite animated.

One voice, a strong Israeli accent, said: “Bravo to Bibi, he is doing a great job, and it is best if he ends the presence of Palestinians in Gaza and pushes the Palestinians in the West Bank into Syria.”

A second male voice, more Western—likely British—agreed: “All of the Palestinian territory must be Israeli, and Israel must dominate the region.”

The first man agreed, adding that with Israel’s nuclear weapons, his suggestion was exactly what should happen.

“Forget global public opinion—it’s nothing but fluff.”

He continued: “All countries are scared of Israel. Americans can’t dictate to Israel, and the British will fall in line via clever maneuvering, at which they excel. Europe is hopeless as a voice.”

“Don’t forget the total absence of any unified Arab or Islamic voice. They are AWOL—absence without official leave—and to be blunt, Bibi is brilliant. Trump is wrong. Canada is not America’s 51st State; America is Israel’s 2nd State. We hold the strings,” he added.

Laughter followed. I could not finish my croissant. I forced myself not to turn around and tell them they were wrong—that what is happening on the ground is horrific for both Palestinians and Israelis, and that Israel’s nuclear arsenal will not save either side from a bleak future.

It remains shocking to me how humanity has watched in silence as carnage unfolded in Gaza and massacres continued in the West Bank—while US and European taxpayers funded the weaponry that has killed over 60,000 people, many still under rubble, half of them children and women.

More than a hundred thousand are wounded, maimed, starved, and will never live normally again.

All this, ongoing, while we sit in the comfort of Sotheby’s cafeteria.

I lost track of the discussion behind me as they ate and drank. Then Sylvia appeared—a tall woman in her fifties with a big smile, a collector of 19th-century paintings. I stood to greet her. She explained she was there for a private sale opportunity but had to leave for a dentist appointment, grimacing as she said it.

We nodded our goodbyes.

When I sat down again, a new voice joined the table behind me—the woman. She addressed Haim, the Israeli man, telling him that his name comes from Chaim, meaning “life,” and that it is associated with celebrating and preserving life, not death.

He replied sharply: “I only care for Jewish life; the others can go to hell.”

I was shocked, but I wanted to hear more to understand the mindset of such extremism. The table fell silent for a moment.

Then the woman spoke again: “Bibi and his cohorts have had a stroke of luck—they have the US at their beck and call and the rest of the world talking but no one is listening. What might shock the world into awakening is if credible journalists and cameras are allowed into Gaza—but you Israelis are too clever for that. And if there is one nationality that can repaint any narrative, it is yours, Haim. I admire that skill, but the future cost is huge.”

I had an urge to leave. As I turned to look for the server, I found myself face-to-face with the three as they split their bill. They got up and continued talking as they walked toward the door.

I caught the woman saying, “You don’t care that your children will pay the price.”

Then they were gone. I paid by credit card, picked up my leather paper case, and walked out—remembering Martin Luther King Jr.’s words:

“The silence of the good people is more dangerous than the brutality of the bad people.”

About the author

M. Shafik Gabr is a renowned leader in international business, innovation, investment and one of the world’s premier collectors of Orientalist art, and an accomplished philanthropist.

During his career, Gabr established over 25 companies plus three investment holding companies including ARTOC Group for Investment and Development which, established in 1971, is a multi-disciplined investment holding company with businesses in infrastructure, automotive, engineering, construction and real estate, over the past three years focusing on investment in technology and artificial intelligence.

Gabr is the Chairman and a founding member of Egypt’s International Economic Forum, a member of the International Business Council of the World Economic Forum, a Board Member of Stanhope Capital, an International Chairman of the Sadat Congressional Gold Medal Committee, and a Member of the Parliamentary Intelligence Security Forum.

Gabr is a Member of the Metropolitan Museum’s International Council and serves on the Advisory Board of the Center for Financial Stability, the Advisory Board of The Middle East Institute, and the Global Advisory Council of the Mayo Clinic.

Through the Shafik Gabr Social Development Foundation, Gabr is helping to improve elementary-school education in Egypt, introducing students to arts and culture and promoting sports and physical fitness for youth. The Foundation has its first Medical and Social Development Center in Mokattam, Cairo, offering free medical and health services.

In 2012 Gabr established in the US the Shafik Gabr Foundation which supports educational and medical initiatives plus launched in November 2012 the ‘East-West: The Art of Dialogue initiative promoting exchanges between the US and Egypt with the purpose of cultural dialogue and bridge-building.

Gabr holds a BA in Economics and Management from the American University in Cairo and an MA in Economics from the University of London.