Conflict Armament Research (CAR), a UK-based organization which investigates weapons’ components, has established that the Shahed-136 drones sold to Russia by Iran are powered by an engine based on German technology – technology illicitly acquired by Iran almost 20 years ago.

The finding – made through detailed examination of components recovered in Ukraine and shared exclusively with CNN – underlines Iran’s ability to mimic and finesse military technology it has obtained illegitimately.

Western officials are also concerned that Russia may share Western-made weapons and equipment recovered on the Ukrainian battlefield with the Iranians. So far, there’s no firm evidence that has happened.

However, relations between Tehran and Moscow have grown much closer. Russia wants Iranian drones and ballistic missiles; Iran wants Russian investment and trade. Russia has become the largest foreign investor in Iran over the past year, according to Iranian officials.

And for the Russians, Iranian drones are a bargain substitute for much more costly missiles, stocks of which are dwindling, according to Western officials. Experts believe that a Shahed-186, for example, costs about $20,000, a tiny fraction of the cost of a Kalibr cruise missile.

Last October, the head of Ukraine’s Defense Intelligence, Kyrylo Budanov, said Russia had ordered about 1,700 Iranian drones of different types. Ukraine has proved adept at taking down the Shahed-136, but that depletes its already scarce anti-aircraft defenses. Despite a relatively low explosive charge, at up to 40 kilograms (88 pounds), an accurate strike by a Shahed-136 can still cause extensive damage.

Powered by German technology

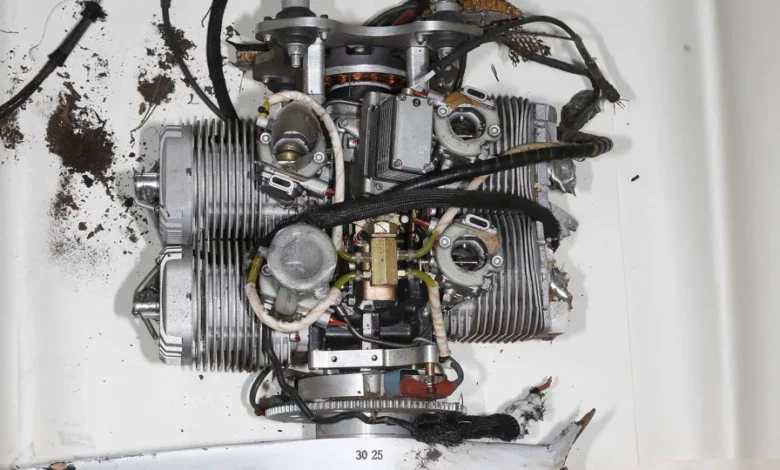

Between November last year and March 2023, CAR was able to examine components in 20 Iranian-made drones and munitions in Ukraine, about half of them Shahed-136s.

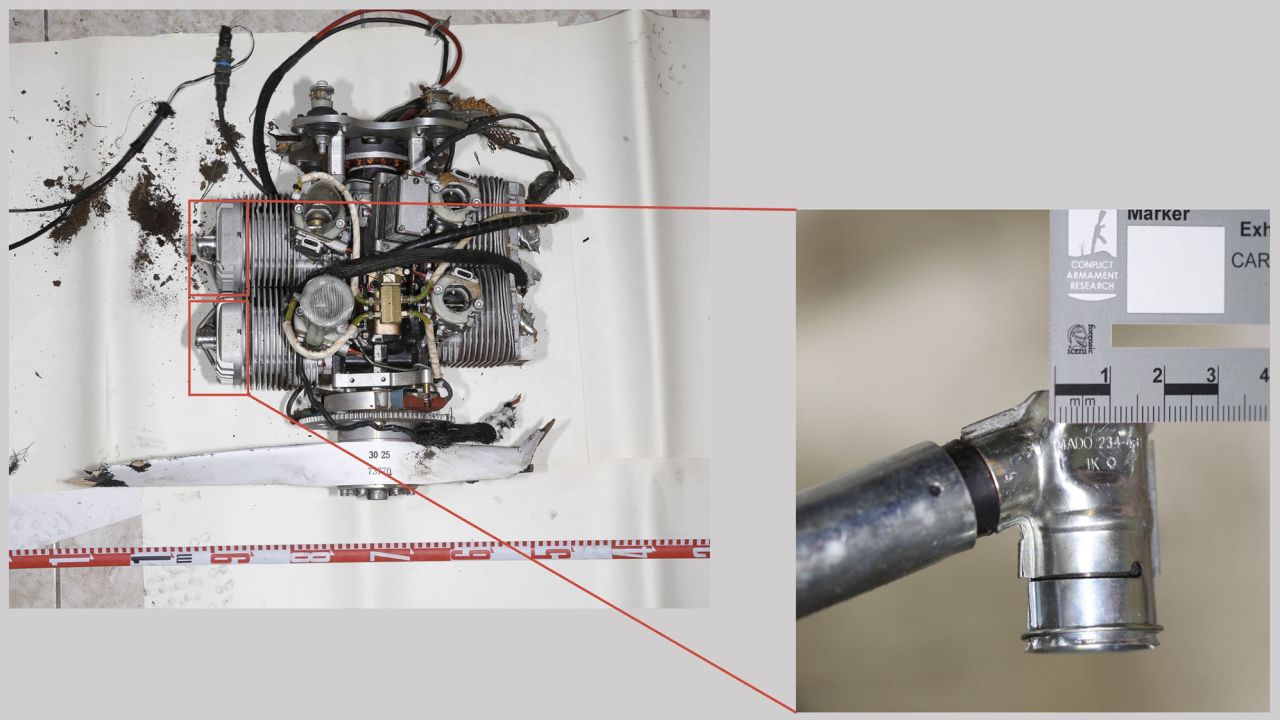

It was able to confirm that the motor in the Shahed-136 was reverse-engineered by an Iranian company called Oje Parvaz Mado Nafar – known as Mado – based in the town of Shokuhieh in Qom province. The company was sanctioned by the UK, US and European Union in December last year.

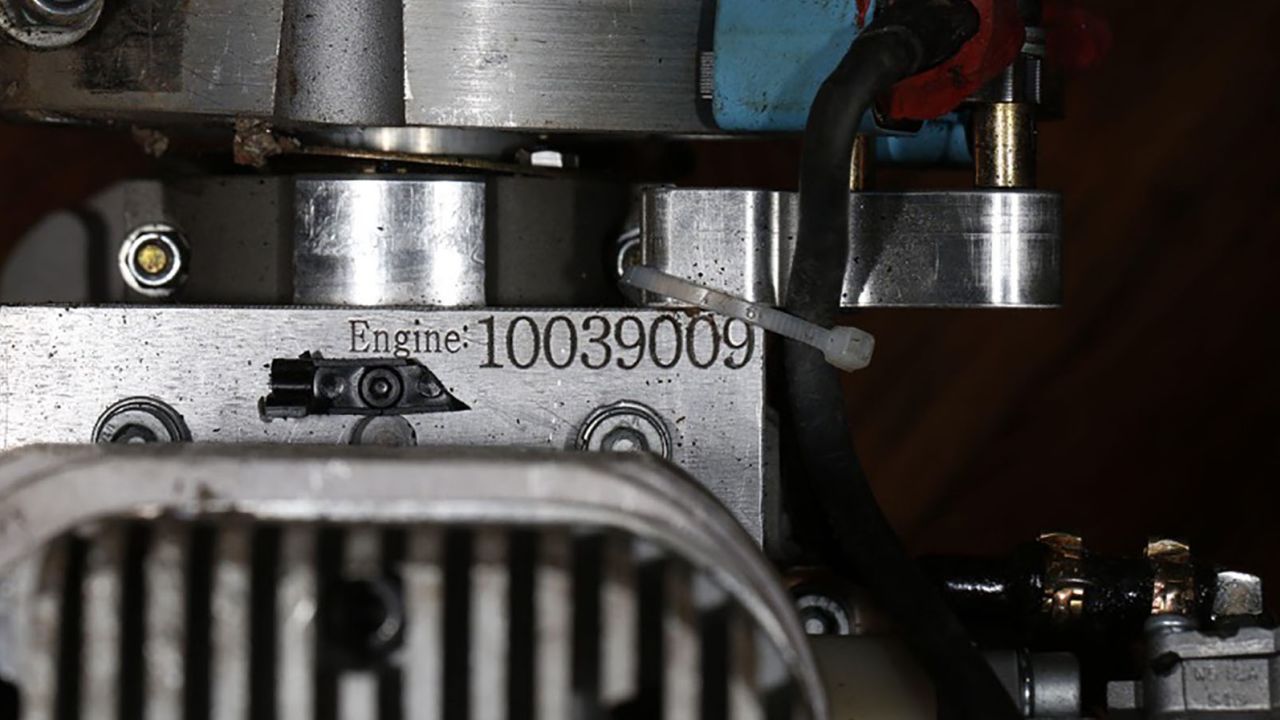

CAR researchers found Mado’s markings on spark plug caps in the drone’s engines, as well as serial number sequences used by Mado.

Mado plays a crucial role in Iran’s expansive drone industry, according to Western governments and the United Nations. The same serial number pattern was also noted by UN investigators examining drone attacks on Saudi Arabia allegedly carried out by Iran’s Houthi allies in Yemen – as well as missile attacks last year against Abu Dhabi, one of the United Arab Emirates.

Taimur Khan, Gulf analyst at CAR, told CNN that Iran’s UAV systems are constantly being refined and modernized and “have proven to be increasingly accurate in terms of their targeting and guidance systems as well as the counter-jamming capabilities.”

A long quest

The design of Mado’s engine speaks to an intense Iranian effort stretching back some 20 years to acquire Western technology for its drones and missiles in the face of widespread international sanctions.

In 2006, Iran illicitly acquired drone engines made by the German company Limbach Flugmotoren. Three years later, an Iranian engineer called Yousef Aboutalebi announced his company had built a UAV engine.

That company would become Mado.

The company appears to have tried to conceal its role in the construction of the Shaheds, according to CAR. Its investigators found that original serial numbers on drone components found in Ukraine had been erased, in an apparent effort to disguise their origin.

“These modifications have prevented investigators from identifying the acquisition networks facilitating the international supply of key components into Iran,” CAR says.

Among other Western components acquired and copied by Iran are Czech-made missile parts. A UN experts’ report in 2020 said that the engine in Iran’s Quds-1 missiles used in attacks on Saudi oil refineries the previous year “was “an unlicensed copy of the TJ-100 jet engine manufactured by PBS Velká Bíteš” in the Czech Republic.

Experts say the Czech engine also appears to have been installed on Iran’s Heidar-2 missile.

The company said it had never supplied the engine to Iran or Yemen, but Iran has become expert at evading controls on sensitive technology, in some instances using front companies. A UN panel found that parts exported by the Czech manufacturer to a company in Hong Kong in 2010 ended up in Iranian missiles used in 2019.

Taimur Khan, at CAR, says that Iran has “acquired Western components and technologies for its UAV programme by taking advantage of the lack of supply chain visibility,” which makes identifying components a critical technique in improving export control and sanction mechanisms.

A deepening partnership

The drone sales have deepened Iran’s relations with Russia, which were already strengthening as the two countries were increasingly locked out of international commerce and the financial system.

“We define our relations with Russia as strategic and we are working together in many aspects, especially economic relations,” Finance Minister Ehsan Khandouzi told the Financial Times last month.

The revenues from the sale of hundreds of Shahed-136 drones to Russia will likely be reinvested in further improving the industry. And the partnership may begin to explore new territory.

Khan believes that “given the fact that Russia is capturing sophisticated Western weapons on the battlefield – such as the Javelin anti-tank missile – and that there is increasing military cooperation between the two countries, and Iran has proven capabilities in this regard, I think it’s likely that they will collaborate on copying these types of systems.”

There is also the possibility that Russia will leverage its cooperation with Iran to develop its own military drone capabilities.

But until that happens, Russia’s military will likely remain an eager customer for hundreds more drones from Iran, a state that has made evading sanctions to build an indigenous weapons industry a fine art.