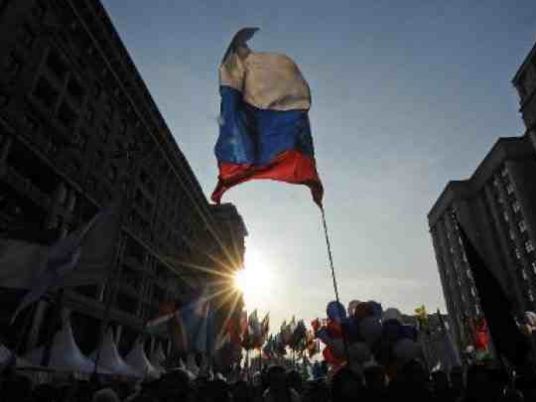

Tens of thousands of President Vladimir Putin's supporters marched through central Moscow on Tuesday in the latest show of increasingly feverish patriotism stirred by the war in Ukraine.

A huge, highly organised march through the centre of the capital to mark national Unity Day came at a time of growing social and economic tensions in Russia, as well as diplomatic isolation over the Kremlin's role in Ukraine.

The march — deliberately, observers say — eclipsed a more modest gathering of hardline nationalists on Moscow's outskirts.

Unity Day was introduced under Putin to mark the 1612 expulsion of Polish occupiers and has grown in importance, alongside a rise in both state-sponsored nationalism and its less controlled far-right version.

Putin, speaking at the Kremlin, said Russians pulled together in the face of outside pressure, in an apparent reference to Western sanctions imposed over the crisis in Ukraine.

"This year we've had to face difficult challenges," he said. "No threat will force us to renounce our values and ideals."

Earlier in the day a visibly pleased Putin laid flowers at the Red Square monument to Kuzma Minin and Dmitry Pozharsky, who helped rid Moscow of the Poles four centuries ago.

Police estimated that some 75,000 turned up for the march and rally in solidarity with the Russian strongman's policies, although they are often accused of exaggerating support for the authorities.

With music blaring through the streets, thousands of Russians, including representatives of all main political parties, marched through Moscow's main Tverskaya Street in a carefully choreographed show that harked back to Soviet times.

Camouflage-clad children were seen among the participants.

"Together we are a force," read one banner, while another proclaimed: "We trust in Putin."

Many expressed support for pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine, where Western governments accuse Russia of stirring up war to bring West-leaning Ukraine to its knees.

"We are united with our brothers in Novorossiya (New Russia)," said Sergei Mironov, leader of the pro-Kremlin A Just Russia party, referring to Moscow's name for the separatist-held regions.

"This is a year of trials when our strength gets tested," said a commentator on state-controlled television broadcasting the event.

Smaller rallies were held across the country.

Analysts say the Kremlin has stirred patriotic sentiment with its annexing of Ukraine's Crimea peninsula in March and backing for separatist insurgents in eastern Ukraine.

But they warn that the nationalism card, with its increasingly militaristic overtones, risks backfiring on Putin, whose rule has been characterised by prevention of spontaneous and potentially uncontrollable political movements.

Ultra-nationalist march

The Kremlin's desire to keep nationalist passions within controllable limits was visible in the high profile given to the Unity Day march, while pushing the less loyal ultra-nationalists into an obscure and distant neighbourhood.

Police estimated that only about 2,000 turned up for that event, far below the 10,000 to 20,000 organisers had been hoping to attract — a result, they said, of pressure from the authorities.

Nationalists of all stripes including those both for and against the rebels in Ukraine had agreed to put differences aside in a show of unity.

Carrying traditional nationalist black-and-yellow banners, hundreds of participants — mostly young men — chanted "Russians forward" as they marched through the bleak southeastern Moscow neighbourhood of Lyublino.

Some marchers chanted obscenities, and others sported a banner reading "Russians against the war with Ukraine."

"I want Belarus, Ukraine and Russia to unite," said one participant, Alexander Dyomin, 57, echoing the ultra-nationalist desire for pan-Slavic unity.

Some 30 people were detained, a lawyer for the ultra-nationalist movement, the Russians, Dmitry Makarov, said on Echo of Moscow radio.

New brand of nationalism

Putin, who has put restoring military pride and a sense of Russia's swagger at the centre of his long presidency, sees nationalism as one of his most potent weapons for maintaining a strong base of support.

"The biggest nationalist in Russia is me," Putin said last month.

But observers say the Kremlin may find itself unable to keep stage-managing these passions.

The relatively small number of far right groups may not be the Kremlin's problem ultimately, some say. The real challenge might come from the unpredictable results of ordinary Russians falling for the nationalist message that Putin, with his policies in Ukraine, has done so much to encourage.

"It is a new nationalism, a nationalism of thousands of people who have fought in a war" in Ukraine, Yegor Prosvirnin, editor of the nationalist website Sputnik & Pogrom, told AFP.

"Russia is pregnant with a new nation, the Russian nation."