It is a mistake to believe that the greatness of ancient Egyptian civilization lies only in its surviving monuments, such as pyramids, temples, tombs, obelisks, and statues, or even in the treasures of its great pharaohs like the treasure of King Tutankhamun and the golden treasures of Tanis. The true greatness of ancient Egypt lies fundamentally in the intellectual thought it offered to all of humanity.

The ancient Egyptians left no field of science, literature, or philosophy untouched; they excelled in all of them, which led all Greek scholars and philosophers to acknowledge their debt to ancient Egypt. Many of them even boasted that they had studied in Egypt under its writers, philosophers, and scientists.

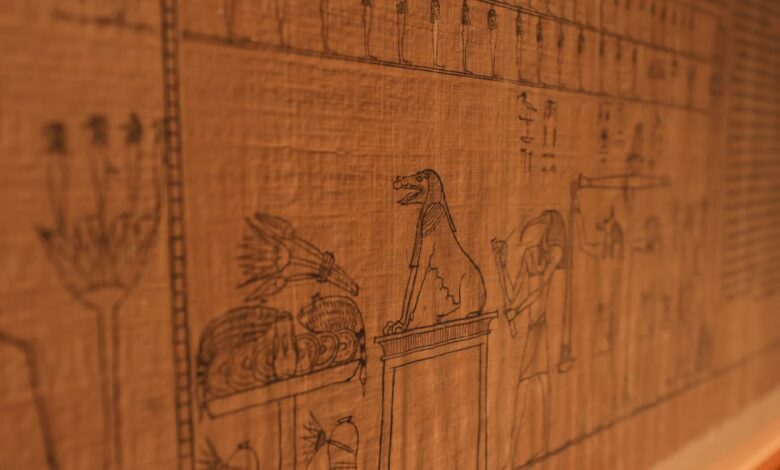

Among the most remarkable discoveries of ancient Egyptian literature is a papyrus from the Middle Kingdom, specifically from the era of King Amenemhat III (1860-1814 BC). It is a copy of an older text, likely dating back to the late Old Kingdom, a period that witnessed violent upheavals that shattered the stability of ancient Egyptian society and ended in a massive social revolution, the consequences of which Egypt suffered for more than a hundred years.

This papyrus is known as “The Man Weary of Life” and is classified as a work of existentialist literature. It was discovered by Karl Richard Lepsius—the head of the Prussian mission to Egypt—in 1843 and is currently preserved in the Berlin Museum in Germany.

The papyrus of “The Man Weary of Life” is a philosophical dialogue written on 184 columns. It revolves around a conversation between one of our great ancestors and his own self, or “Ba,” which represents his soul. The man, who has fallen into despair, speaks of his suffering from loneliness and both psychological and physical pain. He sees no solution other than to end his life by suicide.

In his view, death has become a lifeline from the suffering of life: “O my soul, my companion since the beginning! Today I speak to you without ambiguity: death stands before me like a doctor’s medicine, like the scent of a lotus at the Nile’s flood, like the release of a prisoner from the injustice of a jail… while life has become a mountain heavier than copper, and my patience a vessel cracked from thirst!”

The man’s soul, which embodies his human conscience, begins its conversation with sympathy. It then starts to warn him that suicide will not lead to salvation from suffering. Instead, it could destroy his chances of bliss in the afterlife and deny him a proper funeral with priests’ chants, burning incense, and offerings.

The soul says: “O troubled one! Do you rush to death as one flees from his own shadow? If you seek death before its time, who will burn incense on the altar of Osiris? You will be buried without ceremonies or rites, and your funerary tablet will be forgotten like the names of enemies!”

Then, the soul moves from a stage of threatening the man with the dangers of suicide to offering him advice, saying: “Listen to the counsel of your life’s companion: Would that you would build yourself a tomb of stone! Would that you would plant trees to shade your grandchildren! Be patient! The sun rises after the darkness of night, and death will surely come like the flood of the Nile.”

Here, the man weary of life speaks of the bitterness of living in a society on the verge of collapse after it has lost its values and disintegrated, with all of its deeply held beliefs crumbling. In response to his soul, the man questions the usefulness of funerary rituals, as the sanctity of tombs has been violated and graves have been plundered. He argues that funerary rites, amulets, and charms failed to protect the dead themselves.

He says: “Look! The builders of luxurious tombs are now under the earth! And the builders of temples lie next to the poor in the fields of the gods! Those great statues have become like dusty ruins, and the names of kings are swallowed by oblivion like clouds in the desert wind… What good is a majestic tomb if its owner becomes food for worms in the darkness of the earth? And where are the offerings from sons that we were promised? As for the gilded funerary tablets, they have been stolen and now serve as shelves in the homes of thieves! We have forgotten who has died, and those who remember us will die! Listen, my soul! Death alone is a just hunter; it spares no prince… and has no mercy on a poor slave.”

The soul continues to coax the man, urging him to abandon his pessimistic thoughts and return to his love for life. It says: “Don’t be like a crocodile moaning in the mud! You are a human created by God to be aware of the secrets of existence!… Cast off your worries like a tattered garment! Hold on to life like a child holds on to his father’s finger. Live to see the lotus flower bloom every morning, and hear the song of the fishermen at sunset… And when death inevitably comes to you in the end, like a guest who is full after the feast, I will carry you on my wings like a phoenix to the world of eternity!”

It appears the soul was ultimately able to convince the man that suicide is futile and that life, despite the pain, is worth holding on to.

It’s important to emphasize that this brilliant philosophical dialogue between a man and his soul, or human conscience, is the oldest philosophical model of a conversation between a person and their inner self from the ancient world. It did not merely diagnose the problem but went beyond that to propose a cure for psychological depression, offering convincing solutions for overcoming it.

Therefore, we wouldn’t be exaggerating to say that the principles of psychology and psychiatry began in ancient Egypt, a civilization that will continue to amaze us with every new secret of the pharaohs we uncover.