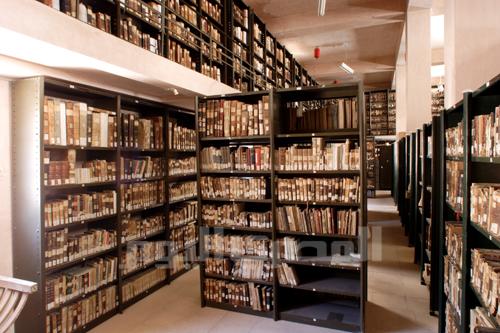

St. Catherine’s Monastery is going digital. The monastery that claims to be the oldest in the world — not destroyed, not abandoned in 17 centuries — has begun digitizing its ancient manuscripts for the use of scholars. A new library to facilitate the process is about five years away.

The librarian, Father Justin, says the monastery’s library will grow an internet database of first-millennium manuscripts, which up until now have been kept under lock and key. Should a scholar want a manuscript, they need only email Father Justin.

“And if I don’t have book but see a reference, I can email a friend in Oxford. They can scan and send it the next day,” he says.

Still, as natural and inevitable as it sounds, that’s quite the sea change. Just 10 years ago, bad phone lines made it hard to connect a call with the monastery. One hundred years ago, it took 10 days to travel from Suez with a caravan of camels.

And when I arrive unheralded, having not even called ahead, a monk shades his eyes, shakes head and — at first — says he will not introduce me to Father Justin.

“What if we said 'yes' to every reporter and scholar that came here? Everyone wants our time. But what about our own work?” he asks.

Not many of the 25 monks cloistered at the Sacred and Imperial Monastery of the God-Trodden Mount of Sinai have email addresses, or operate Mac G5 computers, or know their megapixel from their leviathan. Father Justin Sinaites is a native of Texas. He wears a black habit and a beard to his chest, and ties his long hair back in a ponytail. He is over six feet tall. When he stands, he keeps his arms ramrod straight at his sides.

Every morning he attends the 4:30 am service — which has not changed its liturgy since AD 550 — and then climbs six flights of stairs to his office in the east wing of the three-story administrative building forming the back wall of St. Catherine’s Monastery. He powers up the G5 and passes the morning making digital photographs of scripture written on papyrus, written on animal hide and written with ink made from oak tree galls.

“It’s amazing, the juxtaposition,” is how he puts it.

A page that may have taken a bent-backed monk weeks to illuminate is clamped under the bellows of the 48MP CCD camera. Snap. Next page. It takes three or four days to do a whole book. There are about 3,300 manuscripts.

Although there are various standard versions of the Bible, these are based on a quicksilver, volatile mass of ancient transcribed scripts that never entirely agree. The scholars trace the genealogies of texts to find the points where the texts diverge and converge. In theory, they should converge on the oldest known text: in the case of the Epistles of St. Paul, that’s about AD 100.

But even this original text is only a copy; in effect, the scholars are sifting the scriptural waters for the breath of a saint.

“Paul didn’t even write his epistles. He dictated them and sent them to the Ephesians. And he said, ‘When you finish with this, exchange it for the letter I sent to the other church.’ In AD 100 all these letters were gathered together,” says Father Justin.

“There are always differences — you never see the same script twice. The differences are always very important,” he says.

On 12 May, scholars came to take multi-spectral images of a book called “Sinai Greek New Finds Majuscule #2,” which was re-discovered in the 1970s. The text had been stored under a floor that collapsed in an earthquake. Underneath its ninth-century text of the Epistles of St. Paul, there is another erased text that becomes visible at certain frequencies of light. The scholars will take 40 photos of each page with different infrared and ultraviolet filters to tease out the sub-text.

If all this sounds a lot like Dan Brown’s best-selling “The Da Vinci Code,” that can only be good for funding.

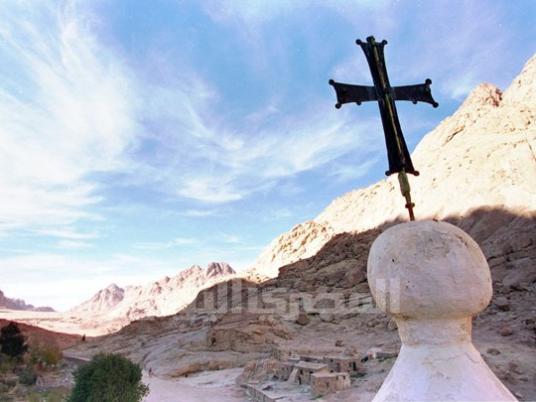

The monastery’s present archbishop, Damianos, who became archbishop in 1973, sees digital technology and the internet as a way of furthering the monastery’s ancient goals to study and preserve the manuscripts, Father Justin says. Though it seems a little counterintuitive, the monastery stuck deep in the Sinai mountains was once considered one of the safer places in the Holy Roman Empire. In internet terms, it was a backup server, and they sent their most valuable manuscripts there. The Emperor Justinian I sent 50 Greek families to defend and feed the monks. These families have become the modern Jabaliya Bedouin tribe.

While preservation once meant pouring boiling tar on marauding heathens, nowadays the barbarian is more elemental: abrasive granite dust that slips between the window and the frame, UV radiation, and alkaline sweat. Gone are the days when the major threat was a camel-riding German named Herman Tischendorff. According to the English travel writer William Dalrymple in his book “From the Holy Mountain,” the monks maintain to this day that the irascible German got the librarian drunk and swapped the “Codex Sinaiaticus” — the earliest existing copy of the New Testament — for a bottle of German schnapps.

Tischendorff then presented the codex to Alexander II of Russia. Some 70 years later the Soviet Union, bankrupt and purportedly atheist, sold it to the British Museum, where it remains.

“We’ve always felt they should return it,” says Father Justin, with admirable understatement.

In January 2011, a bound true-scale facsimile of the complete “Codex” was published for the first time. You can find the whole manuscript online.

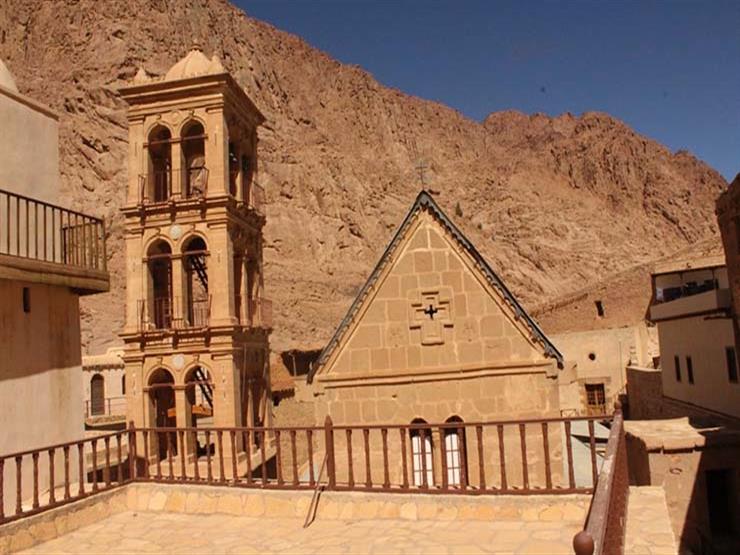

Back in Tischendorff’s time, the manuscripts and catalogues were stored in a central, ground-floor locale designed by the bibliophile Archbishop Nicephorus Marthalis. That library, finished in 1734, was only replaced in 1951, when the current three-story administrative building was opened after 20 years of construction. The collection was installed on the top floor, in two rooms either side of a central staircase.

A bronze plaque still commemorates King Farouk, who cut the ribbon and was promptly (within months) evicted from office.

In 2009, the monastery commissioned UK architect of traditional design Dmitri Porphyrios to make an aesthetic design for a new library. Engineer Petros Koufopoulos produced the final plans, which have been approved by the Egyptian Antiquities Ministry and are pending final approval from the monastery’s independent funding body, the St. Catherine Foundation.

The animal-hide manuscripts have been swaddled in bubble wrap and carefully stacked in barcoded plastic boxes in a former dining room. The modern books are heaped in an adjoining room.

“You wait so long you want to see some action,” says Father Justin, who can’t wait for the new library to be up and running. He hopes to blog about the construction.

“These days everyone has a blog,” he says.

For its 17 centuries, the monastery has had to justify itself toward one center of power or another, from Rome to Constantinople to Cairo. Political and regulatory powers remain with Cairo, while financial power now lies with the St. Catherine Foundation. The body of mainly Greek benefactors has offices in London, New York and Geneva.

But until very recently, the monastery has enjoyed physical isolation. Now you can fly directly from Moscow to Sharm el-Sheikh and take a bus to St. Catherine. The world is streaming through the keep in fiber-optic glass strands. True to form, the monastery has been able to adapt. But it has had to consent to forgo some of its carefully guarded solitude.

Still, if you look upward, you can see the house of an actual hermit, Father Moses.

“We’re trying to find ways we can be open but keep the monastery’s peace. The archbishop said it is a privilege to live here and we have a responsibility to share the spirituality that has been preserved. We can’t be museum open at all hours, and we can’t be closed. It’s a delicate balance,” Father Justin says.

Its continued existence, Father Justin says, speaks of the coexistence of Greek Christian monks and Islamic rulers.

“The library is not just Christian documents. It includes Arabic and Turkish state documents,” he says.

He unwraps a Turkish firman, or official decree, from 1900. It is a lavish scroll, lined with green silk, stored in pink silk and inscribed with red, black and gold arabesques. "The Sultan Abu Hamid confirms the archbishop," it reads.

“We may seem isolated,” he says. “But in a sense we’re keeping these texts for the whole world.”