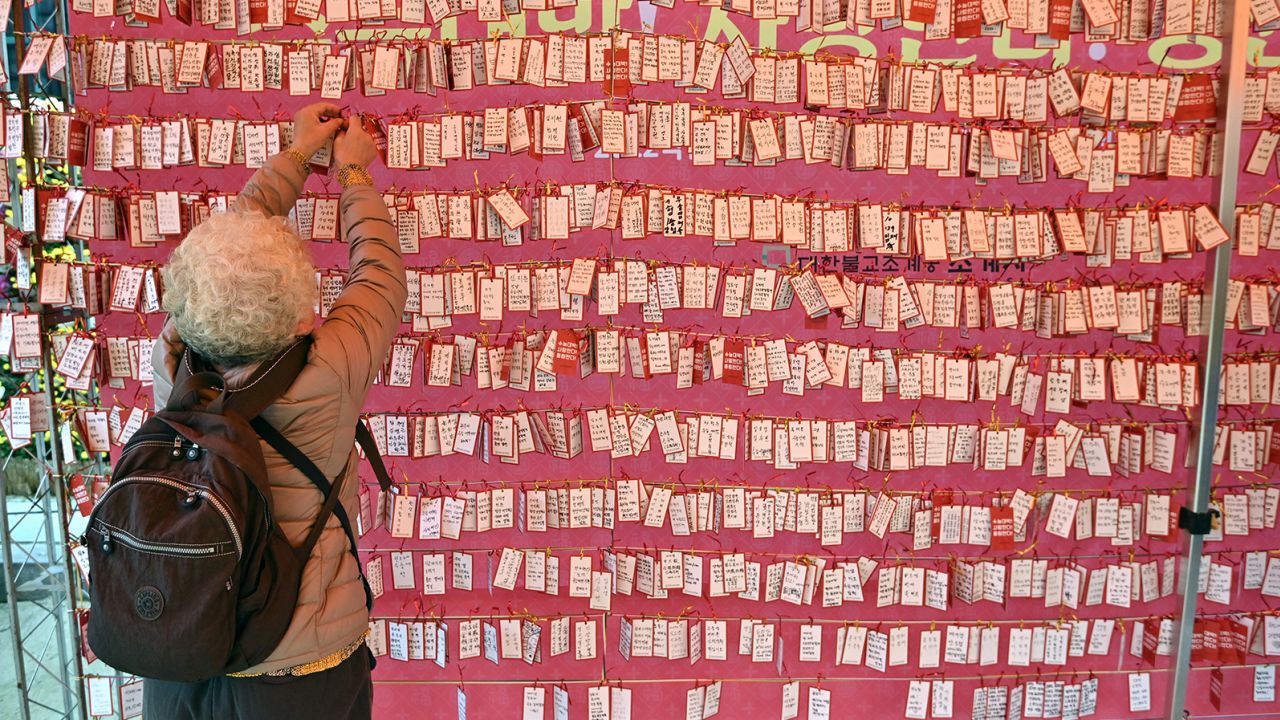

Their goal? That by the time these toddlers turn 18 they will have grown into students able to ace the country’s notoriously uncompromising, eight-hour national college entrance exam known as the Suneung and win their place in a prestigious university.

But getting to this point involves an arduous, expensive journey that takes its toll on both parents and children alike. It’s a system widely blamed by researchers, policymakers, teachers and parents for a litany of problems, from inequality in education to mental illness in the young and even the country’s plummeting fertility rate.

Hoping to solve some of these issues, the South Korean government took a controversial step this week: making the college entrance exam easier.

Officials will remove so-called “killer questions” from the Suneung, also known as the College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT), Education Minister Lee Ju-ho said in a news briefing Monday.

These notoriously difficult questions sometimes include material that isn’t covered in public school curricula, Lee said, lending an unfair advantage to students with access to private tutoring. He added that while it was “a personal choice” for parents and children to seek tutoring, many feel forced to do so due to the intense competition to do well in the exam.

The ministry “seeks to break the vicious cycle of private education that increases the burden for parents and subsequently erodes fairness in education,” Lee vowed.

Mind-bending questions and a life-changing exam

By the time South Korean teenagers enter high school, much of their lives revolve around academic results and preparing for the day of the CSAT – a date that is widely seen as making or breaking one’s future.

They have good reason to be anxious; the “killer questions” range from headache-inducing advanced calculus to obscure literary excerpts.

The ministry published several sample questions this week, drawn from past CSAT tests and mock exams, to illustrate the types of problems that would be removed in future tests.

One question, combining math concepts such as the differentiation of composite functions, was deemed “more complicated than those covered in public schools, which can cause psychological burden on test takers,” the ministry wrote. Another sample question asked test takers to analyze a lengthy passage about the philosophy of consciousness.

In the face of such tough odds, most Korean students enroll in extra tutoring or classes at private cram schools known as “hagwons.” It’s common for students to go from their regular school classes straight to evening hagwon sessions, and then to continue studying by themselves into the early morning hours.

As a result, the hagwon industry in South Korea is massive, and profitable. In 2022, South Koreans spent a total of 26 trillion won (almost $20 billion) on private education, according to the Ministry of Education.

That’s almost as much as the GDP of such nations as Haiti ($21 billion) and Iceland ($25 billion).

Last year, the average student across elementary, middle and high schools spent 410,000 Korean won (about $311) per month on private education, said Lee – the highest figure since the education ministry began tracking figures in 2007.

Cycle of inequality

Hagwons have become so prevalent in South Korea that last year 78.3% of all students from elementary to high school participated in private education, according to the education ministry. That places huge pressure on the few families and students who can’t afford the extra classes.

And the competition for university admission is steeper in a country where nearly 70% of students enter higher education – a higher proportion than in other wealthy nations, with the United States at 51% and the United Kingdom at 57%, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

It’s why many South Korean parents, across various income brackets, pour their resources into their children’s education, for fear they will fall behind otherwise.

But this system deepens and perpetuates educational inequality, experts argue. The burden is significantly higher for poorer families, who tend to spend a much higher proportion of their income on their children’s education compared to wealthier households. And still, the playing field remains uneven, with studies showing a clear gap in student achievement between low and high income families.

On Monday, the education minister singled out hagwons for criticism, accusing them of being “private education cartels” that profit off the anxiety of parents and students.

“Parents, teachers and educational professionals all want the government to take an active role so that private education can be absorbed into the (public) school education,” Lee said, promising to make the system fair and to “eradicate” hagwon culture.

To this end, the government has set up a temporary call center for residents to report wrongdoings by hagwons and private academies, he said.

He added that the government will also provide more after-school and tutoring programs within the public sector, and provide better childcare services to prevent students from being “cornered” into attending hagwons.

The cost of excellence

This educational rat race also takes a heavy toll on both students and parents.

Critics have long argued that the burden on students is one factor driving a mental health crisis in the country, which has the highest suicide rate among OECD nations.

Last year, the Ministry of Health warned that the suicide rate was increasing among teenagers and young adults in their 20s, partly due to the lingering effects of the pandemic.

A 2022 government survey added to the grim picture. Of the nearly 60,000 middle and high school students surveyed nationwide, almost a quarter of males and one in three females reported experiencing depression.

In a previous report, nearly half of Korean youth aged 13 to 18 cited education as their biggest worry.

Education weighs heavily for parents, too. Experts believe the staggering expenses are a major factor behind South Koreans’ growing reluctance to have children – along with other burdens like long working hours, stagnant wages and sky-high housing costs.

South Korea is regularly ranked the most expensive place in the world to raise a child from birth to age 18, in large part due to the cost of education. Many couples feel they must focus their resources on just one child, if they have kids at all.

Last year, the country’s fertility rate, already the world’s lowest, fell to a record low of 0.78 – not even half the 2.1 needed for a stable population and far below even that of Japan (1.3), currently the world’s grayest nation.

“The costs of child-raising are high, and represent a large part of the budget of low-income families. Without additional income, having a child leads to a lower standard of living, and low-income families face a poverty risk,” said the OECD in a 2018 paper, adding that “giving up or postponing childbearing is one way to avoid poverty.”

The government itself has long grappled with this issue, saying in 2008 that families were “heavily burdened by excessive spending” in childcare and education. Without new policies to reduce this burden, the country risks “further exacerbating the problem of low birth rates in our society,” it warned.

A step in the right direction?

Efforts to fix the problem so far have proved largely ineffective. The government has spent more than $200 billion over the past 16 years to encourage more people to have children, with little to show for it.

Activists say South Korea needs deeper change instead, such as dismantling entrenched gender norms and introducing more support for working parents.

Targeting the CSAT, some hope, could be a step in that direction. Some groups, such as the civic organization The World Without Worry About Private Education, welcomed the decision, saying it was necessary to prevent children from being “immersed in excessive competition.”

But others aren’t convinced, with some critics online calling it a surface-level solution to a more complex issue, coming as the government looks to shore up support ahead of next year’s general election.

And many high school seniors, preparing to take the exam in November, have complained they feel blindsided by the abrupt change after spending years studying material they thought would be included. Some agreed the private education sector needed reform, but doubted the effectiveness of this move.

“From the standpoint of a current high school senior, I don’t think private tutoring will decrease just because killer questions are eliminated,” one user posted on Instagram.

Another wrote on Twitter: “I think the way to get rid of the private education craze is not to remove killer questions or lower the difficulty of the CSAT, but to improve the job market environment where regardless of your educational background, you can work at a safe place, receive a sufficient wage, and have human rights guaranteed.”

CNN’s Gawon Bae contributed reporting.