There’s something risky about going to see performance art and contemporary dance — especially dance that is not performed on a stage. You agree to put yourself in a situation where you might be a participant. Someone might talk to you, touch you, your image might appear in the documentation of the work, you might look confused. This leads to a state of heightened anticipation. It’s a bit like real life, but more so.

The performances of TransDance 2012, the first Cairo phase of which finished in late October, tended to push this and to ask a lot from audience members. In one, they were asked to help build a table, in two they were asked questions in a somewhat aggressive manner, in another some had to dodge saliva. Some events relied on members of the public for their existence — like an afternoon of dramaturgy consultations, for which people were meant to show up with a dramaturgical problem they wanted to discuss one-on-one for 40 minutes.

But despite all this, this phase of TransDance didn’t really seem to be for audiences. It wasn’t well publicized. It had no website and the schedule wasn’t easy to come by —people asked in vain on the Facebook page. Even if you did get a schedule, some events were missed off, there were quite a few last-minute schedule changes, and some descriptions were quite misleading. Even the performers were confused about when they were meant to be performing. In a further potentially alienating move, the schedule and the events themselves were in English.

As a result, even though all the events were free, the audiences were mostly pretty small, sometimes almost non-existent. Only one person turned up with a dramaturgical problem, so that event stalled pretty quickly. For an event called “Open Your Bags,” the audience consisted of myself and one other person.

The performers and organizers made up the bulk of most of the audiences and were the most enthusiastic participants. All linked by their ties with Adham Hafez, founder of TransDance, over half were Europeans, and the others were Egyptians. A core part of the participants was a European group that had worked together before, and is working on a project that will partly take place in Cairo next year, called “A Future Archaeology.”

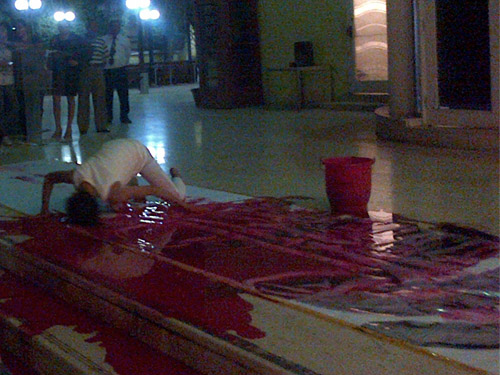

Highlights included an unnerving improvised piece by Egyptian actress Moataza Abdel Sabour and German artist Anke Koschinski, in which Abdel Sabour read poems she had written since the 25 January uprising. Sofia Balogh’s silent, deconstructed belly dance was also interesting — all the moves were there, but it didn’t have the usual effect at all. Deborah Stokes contributed with a challenging, funny performance and a beautiful documentary about Indian dance. It was tantalizing to see an extract of Doa Aly’s film “49 Ballet Lessons,” in which she slowly struggles to learn ballet while wearing a defiant, otherworldly gold leotard.

Some workshops at the Cairo Contemporary Dance Center — not listed on the schedule and attended mainly by the center’s students — seemed to go down really well. When I walked into one led by Peter Stamer, one of the German performers, all the participants were laughing uproariously, and later they meticulously observed and gave feedback on each other’s movements in a discussion that they seemed to value highly.

So there clearly were beneficiaries. One of the Egyptian performers, Mirette Mechail, said installing the soundtrack of a previous performance in the TransDance exhibition at the Medrar for Contemporary Arts space was a really interesting experience, as it was a very simple piece that could be read on different levels, understandable to anyone who speaks Arabic, but also offering footsteps, breaths, piano and violin music.

Mechail said another good thing that came out of the festival, for her, is that she will be creating a piece with Abdel Sabour and Koschinski, based on their improvisation. She said that similarly, in the last edition of TransDance, she danced for the first time with a dancer she had known very well for several years but never danced with before, and the two have since become regular collaborators.

For outcomes like these, and for bravely putting on challenging, experimental events, the likes of which you’d be hard pressed to find elsewhere in Cairo (in an atmosphere that isn’t always sympathetic), it is great that the festival exists.

And TransDance 2012 is ambitious. Hafez said at the press conference before it started that, among other things, the festival would consider the body outside of terms of beauty or athleticism, challenge notions of what performance can be, explore the idea of the body as a document, and think about the relationship between contemporary dance and sound by commissioning silent dances and dances that consisted only of sound.

This ambition was matched by the amount of institutional support it mustered — the British Council, the Goethe Institute, the Netherlands Embassy, Medrar, Cimatheque, the French Cultural Center, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, the Cairo Contemporary Dance Centre, Oyoon Art Group, Residency Unlimited NYC and ArteEast are some of the organizations that offered support in some way.

Hafez, who seemed to put the whole thing together almost single-handedly, feels that the Cairo part of the festival went very well, that the discussions had been extremely interesting. But audiences, it seems, were largely not privy to those moments. Hafez says the organizers are now assessing the festival’s success by carrying out surveys, interviewing participants and partners, and gauging audience reactions.

Perhaps armed with this information, they will make improvements. If the organizational problems were ironed out, if it were slightly less ambitious in terms of the number of ideas it tackled, if the works were allowed to speak for themselves, if there were more publicity and more Arabic-speaking participants, then TransDance could really be a major event on the arts calendar, and audiences would go, despite the risk.