Thanks to Egypt’s third largest listed real-estate developer, SODIC, a slew of metal sculptures six to nine meters high will soon grace a small stretch of the Cairo-Alexandria Desert Road.

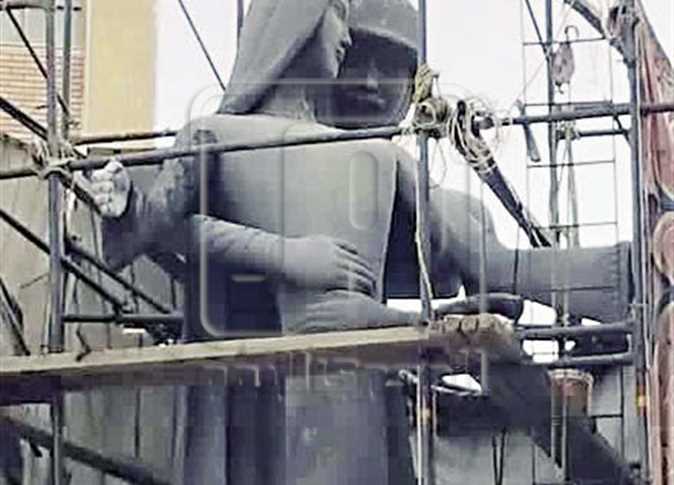

The sculptures that currently occupy a large sandy lot next to SODIC’s headquarters were produced by 20 Egyptian and foreign sculptors as part of SODIC’s first Art Symposium. They present fantastic interpretations of the human form inspired by the 25 January revolution. Some are colorful, others pensive, organic or geometric. Clustered at the lot, the sculptures seem intriguingly alien, a colony of surprising creatures in an idyllic surrounding.

The “Metal Symposium” held in May is the largest sculpture symposium in Egypt, outside of the state-sponsored Aswan Sculpture Symposium, and Mohammed Talaat, the departing director of Cairo’s Palace of the Arts, was recruited to spearhead and conceptualize the project.

“The concept is about movement, transformation, and looking toward the future,” Talaat explains.

The company approved the concept as it wanted the artwork to respond to the revolution, capturing “the transformative historical moment Egypt is experiencing and the freedom to imagine an alternative future,” as stated on SODIC’s website. It also matched SODIC Art’s announced vision to make “art part of everyday life.”

“Egypt has a lot of untouched talent, and SODIC would like to provide artists with both resources and exposure,” Nadine Okasha, representative of SODIC’s marketing department, told Al-Masry Al-Youm.

Participating sculptors find the symposium an effective way of supporting art in Egypt, given the limited funding opportunities outside of the official establishment. Yet concerns remain about the emerging trend of private corporations funding and curating art projects in Egypt – initiatives often interpreted as alternative branding and marketing tactics with limited outreach to the public.

Corporate art funding also has the potential to limit what is produced as artists are required to respond to assigned themes and forms that are easily marketable and employed to the companies' benefit – in the case of SODIC, some of the artworks it sponsors would be used to embellish its housing developments.

The idea of the art symposium came about last December, but at that time the works were conceptualized as stone sculptures that would be used as part of the landscaping of Allegria, a luxury residential complex that creates a well-irrigated paradise escape from the surrounding desert.

After the revolution, new plans were drawn up.

“We wanted to capture some of the energy of the revolution and gear it toward art and culture,” says Okasha.

The sculptures would be figurative, and they’d be of monumental proportions.

“We decided to make them from metal since it’s a more flexible material that allows greater heights and can be completed more quickly,” Talaat explains.

Many of the artists at the symposium were accustomed to working in stone on non-figurative subjects. Working in a less familiar terrain may have helped to produce some very playful interpretations of the human form, such as Egyptian artist Said Badr’s “Hares Al-Tareekh” (The Guardian Angel of History) that’s made up entirely of small metal tubes; and Hesham Abd Allah’s “Thawra Khayal Ma'atah” (Revolutionary Scarecrow), a jumble of metal pieces forming a scarecrow.

“Working figuratively in metal, and on such a large scale is a great opportunity that poses a challenge to participating artists,” says Romanian artist Carmen Tepsan who produced “Place for Passing the Wind” – her largest work to date – for the symposium.

Some works sidestepped direct engagement with the revolution theme, focusing more literally on the idea of motion.

But Indian sculptor Gopinath Subbana and Egyptian artist Ehab El Laban chose to respond directly to the announced theme. In Subbana’s sculpture, titled “Utopia,” a black building is riddled with tiny cutout human figures. On top of the building, the missing cutouts are amassed, clambering up a spire topped with a waving flag.

Laban’s “Waraa' Meissatar” (Lined Paper) depicts an abstracted human form holding metal paper above its head. The metal is inscribed with various political slogans, from the revolutionary chant, “Hold your head up high, you are Egyptian,” to the Muslim Brotherhood slogan “Islam is the solution.”

Striking a very different tone, Iraqi artist Anas al-Alousi dealt with the pain that revolutions can leave behind in one of the more moving and less triumphant pieces at the symposium. Alousi’s work “Al-Mohager” (The Emigrant) is a flowing shape, moving forward laboriously, dragging behind him “his past pain, memories and sadness.”

While some of SODIC’s arts initiatives might be of limited access to the public, the metal sculptures should eventually find their home in a very public place: spaced out outside SODIC’s gates along the highway, once the company gets the necessary permits. The public will, however, miss out on part of the experience as the way the sculptures are currently grouped at the construction site creates an unconventional art-viewing experience. The other-worldly sculptures come alive in their interactions, creating the art gallery equivalent of walking through a zoo, gawking at wild, rare, and new specimens in their natural environment.

A large-scale infusion of art is sure to generate dialogue and excitement on the highway, either way. They certainly will not go unnoticed, and might provide a welcome dose of other-worldly pizazz to the desert road.